Flooding in Rosewood in Horry County, SC, September 24, 2018 (All photos by Allison Hardin with exceptions of FEMA photo from Hurricane Floyd and Charlotte image.)

It has been a few weeks of drought on this blog, but just the opposite in North Carolina, where Hurricane Florence dropped up to 30 inches of rain in some locations, and floods migrated downstream via numerous rivers to swamp cities both inland and near the coast. Now, Hurricane Michael threatens to compound the damage as it migrates northeast from its powerful Category 4 assault on the Florida Panhandle, with storm surges up to 14 feet in areas just east of the eye, which made landfall near Panama City.

The blog drought was the result of both a bit of writer’s block, mostly induced by a busy schedule that included two conference trips over the past three weeks, combined with a bit of fatigue and a few significant diversions of my personal time. But that may be okay. My intent was to write about the recent hurricane along the East Coast, and sometimes letting the subject ferment in the mind results in a more thorough and insightful perspective. I hope that is the result here.

Storms never happen in a vacuum. In a world with relatively few uninhabited places, their impact is the result more of patterns of human development and the legacy of past choices in land use and building practices than of the storm itself, which is, after all, simply a natural and very predictable event. Hurricanes were part of the natural cycle on this earth long before humans took over the planet (or thought they did).

Hurricane wind warning at bridge in Socastee, South Carolina

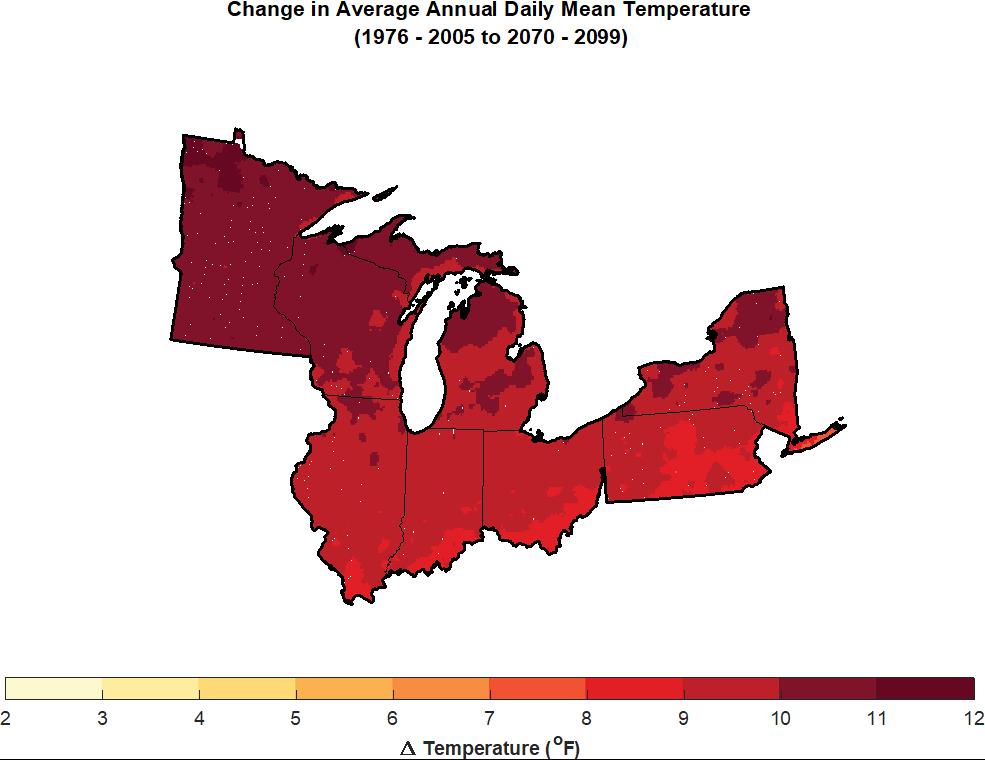

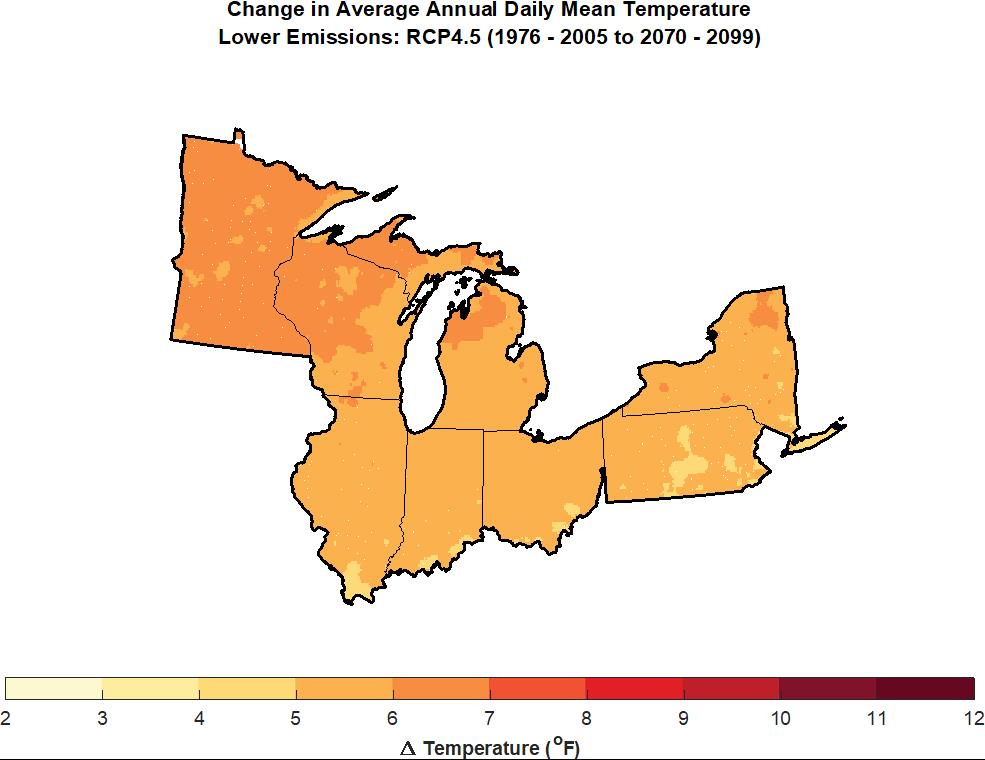

But they appear to be getting worse, and climate change, most of it almost surely attributable to human activity, is an increasingly evident factor. Meteorologist Ken Kunkel, affiliated both with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and North Carolina State University, stated that Florence produced more rain than any other storm in the last 70 years except for Hurricane Harvey last year. According to Kunkel, five weather stations over an area of 14,000 square miles in the Carolinas recorded an average of 17.5 inches. Harvey’s average was 25.6 inches. By comparison, Chicago averages about 37 inches for an entire year. Such heightened precipitation levels are in line with expected impacts of climate change.

What became obvious to me early on was that Florence would rehash a certain amount of unfortunate North Carolina history regarding feedlot agriculture. I am familiar with that history because 20 years ago I authored a Planning Advisory Service Report (#482) for the American Planning Association, titled Planning and Zoning for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations. (In that same year, APA also published PAS 483/484, Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery and Reconstruction, for which I was the lead author and project manager.) I want to emphasize that what happened in North Carolina was not unusual. Nationwide, many states have laws dating to the 1950s that exempt all or most agricultural operations from county zoning ordinances. Most of these were intended to create a friendly regulatory environment for family farms, and they were often followed by other “right-to-farm” laws designed to shield farmers using conventional farming methods from nuisance lawsuits. Only later, as the large feedlots known also by the acronym “CAFO” became widespread, did it become clear that such exemptions, by then fiercely defended by industry groups, became giant loopholes for the detrimental environmental impacts of such operations. This story has been repeated in Iowa, Missouri, Utah, and numerous other states.

In North Carolina in 1991, State Senator Wendell Murphy, who owned a direct interest in the growing Murphy Family Farms, engineered passage of a law widening the state’s exemptions to include CAFOs. Within two years, as I noted in the report, North Carolina’s hog population shot up from 2.8 million to 4.6 million. Today, the number is at least 9 million. A public backlash at the impacts of CAFOs resulted in a new law in 1997 that included a moratorium on new waste lagoons, but by then, although the hogs were firmly ensconced in a growing number of feedlots, the figurative horse was out of the barn. Many counties in eastern North Carolina, where the industry was concentrated, were slow or reluctant to use their newly regained powers. In any case, various large operators were effectively already grandfathered into continued existence. Today, consolidation within the industry has left Smithfield Foods in possession of most of the business in North Carolina, yet Smithfield itself was acquired by the Chinese-owned WH Group several years ago.

Grenville, NC, September 24, 1999 — The livestock loss and potential health hazard to Eastern North Carolina is huge. Here volunteers have towed in dead and floating cattle from a nearby ranch at Pactolus, NC (just North of Greenville), trying to remove them as fast as possible to lower the potential health hazards associated.

Photo by Dave Gatley/ FEMA News Photo

Along came Hurricane Floyd in 1999. The low-lying plains of eastern North Carolina, always vulnerable to flooding, were deeply awash, but worse, filled with millions of pigs and poultry and their excrement in manure lagoons. Hurricane Dennis just weeks earlier had dumped 15 inches of rain on the region, and Floyd dumped even more in some areas. The Tar and Neuse Rivers, among others, badly overflowed their banks and inundated numerous farms. More than 110,000 hog carcasses, and more than 1 million chicken and turkey carcasses, floated downriver while waste lagoons were breached, creating a stench-filled public health disaster only partly solved when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency brought in huge incinerators to burn carcasses, though most animals were buried. It was a fiasco that did not have to happen at the scale on which it occurred.

Fast forward to this year and Hurricane Florence, presuming a surfeit of lessons to be learned from the 1999 disaster as well as later storms. As Emily Moon notes in the Pacific Standard, North Carolina has had opportunities over the past 20 years to introduce serious regulatory change, but various factors foiled those chances, and North Carolina remains the nation’s second-largest hog producer, having pushed aside every state but Iowa. The industry has evolved, but the problem remains. The state has bought out 46 operations since 1999 and shut down their lagoons, but the vast majority remain in operation. The numbers changed in Florence—more than 3 million chickens and 5,500 hogs dead and afloat in the flood waters—but the devastation rooted in CAFO practices continued. Coal ash landfills associated with power stations added to the environmental impacts. And the beat goes on, in a part of the state heavily populated by African-Americans, many too poor and powerless to challenge the system effectively without outside help.

I mention all this aside from the obvious human tragedies of lost lives, ruined homes, and prolonged power outages affecting some 740,000 homes and businesses.

Flooding at Arrowhead Development in Myrtle Beach, SC, September 26, 2018

Still, there are significant lessons available from Hurricane Florence outside the realm of mass production of poultry and hogs, and I want to offer a positive note. One is that, while only about 35 percent of properties at risk of flooding in North Carolina have flood insurance, which is available from the National Flood Insurance Program, neighboring South Carolina ranked second in the nation with 65 percent coverage. While I do not know all the details behind that sizable difference, it seems to me there is surely something to be learned from a comparison of these results and how they were achieved. They come in the context of a “moonshot” by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to double flood insurance coverage nationally by 2022. That will happen when South Carolina becomes the norm rather than the exception. Sometimes we can use these events to push in the right direction. Texas, for instance, has added 145,000 new flood insurance policies in effect since Hurricane Harvey; the question will be whether the new awareness wears off as memory of Harvey fades, or whether the state can solidify those gains. For that matter, can the states in the Southeast—the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida—leverage the lessons of Florence and Michael to push in the same direction?

Hidden Valley drainage restoration project, Charlotte, NC. Image courtesy of Tim Trautman.

Recently, Bloomberg Business News offered an example within North Carolina of how differently floodplains could be managed by highlighting the case of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. I worked for several years in a series of training workshops on flood resilience with Tim Trautman, the manager for the engineering and mitigation program for Mecklenburg Storm Water Services, so I am familiar with their intriguing story. The county for many years has used a stormwater utility fee on property owners to fund its own hazard mitigation program, using the money to buy out flood-prone properties and increase open space in its floodplains. The result has been a significant reduction in flood-prone land and buildings. The question is not whether Charlotte is successful, but what state and federal programs and authorities can do to encourage and support such efforts and make them more commonplace.

Every serious disaster offers lessons and opportunities, and I am not attempting here to pick on North Carolina alone. Other states face their own challenges; Iowa, for one, is undergoing a somewhat muted debate about the impact of its own farm practices on downstream flooding and water quality, in part as an outgrowth of the 2008 floods. What is important is that we use these windows of opportunity, the “teachable moments,” as they are sometimes known, to initiate the changes that are surely needed for the long term in creating more resilient, environmentally healthy communities. What we do not need is a natural disaster version of Groundhog Day.

Jim Schwab