It was spring break in the Chicago Public Schools this past week (April 11-15). Despite busy lives, I thought my wife and I should do something special with Alex, our 13-year-old grandson, so I proposed a visit to Springfield, the Illinois capital, to visit the Abraham Lincoln Museum, which we had never seen. The museum is part of a complex, opened in 2005, that includes the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, an invaluable resource for students and scholars on about Lincoln, the Civil War, and related historical topics, and the Illinois State Historical Library, founded in 1889. Across the street sits Springfield Union Station, which now contains an exhibit about the 2012 Steven Spielberg movie titled Lincoln. The library and museum are connected by a walkway above the street.

From Chicago, Springfield is a fairly easy day trip, about three to three and a half hours each way, depending on traffic. The Lincoln Museum and the State Capitol are popular field trip destinations for Illinois schools, particularly those in central Illinois. Even with many schools out on the day we came, the museum was an obvious magnet for smaller groups of teens and for families. Lincoln, despite nearly 160 years’ distance in time from us today, remains one of the most fascinating figures in U.S. presidential history. The museum notes that only Jesus Christ may be the subject of more biographies than Lincoln himself. It is interesting to contemplate that both had more obscure beginnings than most major historical figures. Does that add to the fascination? I suspect that may well be the case.

Others have written about the museum and library since it opened, but this is a unique time to visit, given contemporary events in Ukraine, where war is ravaging an entire nation much as it did our own in the 1860s. One is almost compelled to make comparisons, and guests were asked to use flower-shaped paper cutouts and glue to write messages on blue and yellow strips that will be displayed to communicate messages of support to the Ukrainian people in their struggle for freedom against a Russian invasion. Blue and yellow, of course, are the colors of the Ukrainian flag. Jean and Alex both wrote their own messages; I wrote mine in Russian, which I learned half a century ago at Cleveland State University in classes half filled with Ukrainian American students. Мир, I wrote on half of the petals I glued together; Свобода, I wrote on the overlying petals: “Peace” and “Freedom.” Unfortunately, I do not know any Ukrainian, but most Ukrainians know Russian. The message is clear enough.

But back to Lincoln and his own times, when a battle raged for the unity of the nation in the face of slave holders determined to maintain white supremacy at any cost in a war that soon enough led to the liberation of more than four million enslaved African Americans. Nothing is ever simple, and Lincoln was not perfect, but his saving grace, unlike a recent American president, is that he never thought he was. He was simply an elected leader who was determined to find a path for his nation through its darkest days, and somehow succeeded. But he was also assassinated by John Wilkes Booth before he could ever see some of his most important gains for equality sacrificed to political myopia and expedience with no opportunity to do anything about it. His own vice-president, Andrew Johnson, proved not only inadequate to the task but riddled with racial bias. Vice-presidents in those days were often mere ticket balancers with little thought given to their abilities to lead the nation. Sometimes, one wonders how much has changed in that respect.

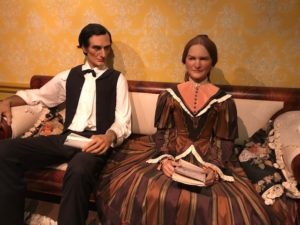

The intriguing thing about the museum is the way in which its designers have chosen to convey to visitors the realities of Lincoln’s life and times. This is truly a modern museum. After taking advantage of the opportunity to “get a picture with the Lincolns,” standing among their images in the lobby, we attended a short holographic presentation called “Ghosts of the Library,” in which a young researcher named Thomas helps people envision how the thousands of documents and historical items in the facility can come to life and share their stories. We realize that every item in the collection has its own story, so many that one could spend a lifetime hearing them all, but, of course, we had only a few hours to get the gist.

The intriguing thing about the museum is the way in which its designers have chosen to convey to visitors the realities of Lincoln’s life and times. This is truly a modern museum. After taking advantage of the opportunity to “get a picture with the Lincolns,” standing among their images in the lobby, we attended a short holographic presentation called “Ghosts of the Library,” in which a young researcher named Thomas helps people envision how the thousands of documents and historical items in the facility can come to life and share their stories. We realize that every item in the collection has its own story, so many that one could spend a lifetime hearing them all, but, of course, we had only a few hours to get the gist.

But that gist then, for us, moved to another theater, in which another narrator walked us through Lincoln’s life from a deprived childhood in a wilderness cabin to the peaks of power in the White House, surrounded by turmoil and controversy, until a gunshot rings out, and we know that Booth has struck at Ford’s Theater, and Lincoln at that point, as Secretary of War Edwin Stanton famously stated, “belongs to the ages.”

Paralleling that sequence are two very different displays, one small, approximating the size of the cabin in which Lincoln grew up, showing him reclined before the light of a fireplace, book in hand, educating himself, for he had only two years of formal education in his entire life. But his absolute fascination with books, and his ambition, served him well. In those days, one became a lawyer through such self-study under the aegis of a practicing lawyer, and it gradually became clear that Lincoln was an intellectual match for most of those around him. He served in the Illinois legislature in the 1830s, in Congress during the Mexican War, and despite periodic defeats including two Senate races, finally won election as president of the United States.

For Alex, seeing the cabin in which Lincoln grew up seemed to make an impression. Although Alex’s life had its challenges before we were awarded custody, he now lives in our three-story brick home with three bedrooms and modern furnishings. Yet, here was Lincoln, teaching himself to read and ultimately making one of the most profound impacts on human history. As I said, perhaps that is what makes the story so compelling.

Across the hall was a replica of parts of the White House and a sometimes-noisy presentation of the Civil War years, with holographic figures in one part of the passageway speaking aloud what was often said in print, in letters, newspapers, and other forums of the time. Some are angry men denouncing him as incompetent, but another is a young woman writing to the president about her brother, serving in the Army, who, in her view, did not need to serve alongside “Negroes” who would be unlikely to fight. The comment is even more compelling in light of our historical knowledge that Black troops, who joined the Union army in the second half of the war, were among the bravest, perhaps in part driven by the emerging news that Confederate forces who captured Black soldiers simply executed them instead of placing them in prisoner camps, although plenty of white troops died under inhumane conditions in such camps before the war ended. What comes across most clearly from this mode of presentation, in a way that written words cannot convey so well, is the sheer nasty divisiveness that infested the country in Lincoln’s time. It makes me wonder what impression this makes on anyone who still approves of the January 6 insurrection at the nation’s capital, inspired by a president who refused to acknowledge loss. When one thinks about Lincoln’s losses on the way to the White House, and the high cost of political division during his presidency, the lack of political grace by some today is even more appalling.

All of that is already compelling enough for a museum visit, but the museum offers one more powerful witness by including what docents warn is a display that visitors may find deeply disturbing. This new exhibit, “Stories of Survival,” opened at the Lincoln Museum on March 22 but was developed by the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center. It displays artifacts and photos from the Holocaust in World War II, but also more recent events such as the migrations of refugees from Middle East hot spots such as Syria. The stories and images are heart-wrenching. In my mind, they force two compelling questions: What is different today from the slaughter of the Civil War, and how does that contrast with events in Ukraine?

The biggest single factor, it seems to me, is that those who were resisting the Union in 1861, and who started the war, as Lincoln anticipated, by shelling Fort Sumter in South Carolina, were doing so not to advance human freedom but to preserve the domination of one race over another. In Ukraine, a sovereign nation, Ukraine, although an offshoot of the politically depleted former Soviet Union, is seeking to preserve its gains in building democracy and freedom. It is the commitment to its own independence and the attraction of a more dignified and promising political system that drives the impressive Ukrainian commitment to fight so well against the odds. The outcome remains in limbo, the destruction remains appalling, but the desire for a free and better life could not be clearer. In other cases, such as Syria (which has been aided by Russia), the power of an oppressive system remains the driving force in continuing genocidal warfare now into the third decade of a twenty-first century that we might have hoped would bring an end to such conflicts. Instead, we find ourselves confronted with evidence of a continued determination by strongmen throughout the world to enforce their will and of the ability of all too many to follow such leaders and excuse their behavior.

It is a sobering realization that the struggle for human freedom, dignity, and equality remains the compelling work of our time.

On the way home, I asked Alex what he felt he had learned from his visit to the Lincoln museum. Sitting in the back seat of the car, he thought for a moment and then said, “Being president is a very difficult job, and lots of people will be against you or criticize you.”

If he got that much out of it at his age, I thought, this trip was well worth the time. I did not ask about the “Stories of Survival” exhibit. It’s a bit much for the most mature adults to take in, let alone a seventh grader.

Jim Schwab