Wilmington, a charming city of just over 100,000 on the far southern edge of the North Carolina coast, has taken some hits from coastal storms in recent years, most notably Hurricane Florence in 2018. Hurricane Dorian this year posed a minor threat but mostly left a trail of 14 identified tornadoes in its wake, a phenomenon familiar in the Southeast, though their association with hurricanes may be less well known elsewhere.

Wilmington Planning Director Glenn Harbeck, who I was told was one of the most knowledgeable people in town for the purpose, on October 8 took me on a boat tour of much of the city’s interior waterfront to let me see and photograph the area along Hewletts Creek, a stream feeding into the Atlantic Ocean behind the barrier island that includes the Masonboro Island Estuarine Reserve. Glenn and his wife have lived in Wilmington for 40 years, during which, he says, they have experienced a succession of hurricanes: Diana (1984), Bertha (1996), Fran (1996), Bonnie (1998), Floyd (1999), Matthew (2016), Florence (2018), and Dorian (2019).

Why it has taken me this long to write about it is another matter related entirely to my own obligations and distractions. At the time, however, I was in Wilmington as the invited keynote speaker for the annual conference of the North Carolina chapter of the American Planning Association. That event was at the city’s convention center, which sits along the Cape Fear River, which basically serves as the city’s western edge, with suburban or unincorporated New Hanover County on the other side. Along with the adjoining Embassy Suites, the complex boasts a boardwalk that allows people to walk to restaurants and other venues in more historic quarters of the city. I joined a party of a dozen at a nearby seafood restaurant, The George on the River, and got to see much of it. Some of the boardwalk appears to need work, but I was not clear on whether that was due to hurricane damage of work in progress. But I can give The George five stars. The food was wonderful and a credit to southern coastal cuisine. (I enjoyed crab-topped salmon with garlic mashed potatoes and spicy collards. I gladly recommend it.) Added appeal derived from the outdoor seating that made for a pleasant evening setting.

But all that followed the boat tour, which came in the late afternoon after a delayed arrival in Wilmington following a long layover in Atlanta on the way from Chicago. The weather had been uncertain, and Glenn was a bit concerned about concluding the trip before it turned rainy or inhospitable, although it never did. It was simply a bit chilly, but my photos have that overcast, gray-sky look as a result.

Compared to some prior tours I have taken of disaster sites, this one was relatively brief with modest expectations. Nonetheless, there are always learning opportunities, and I had never visited Wilmington before. Touring by boat allowed a different perspective than by land. Certain factors became readily apparent, with Glenn supplying ample explanation.

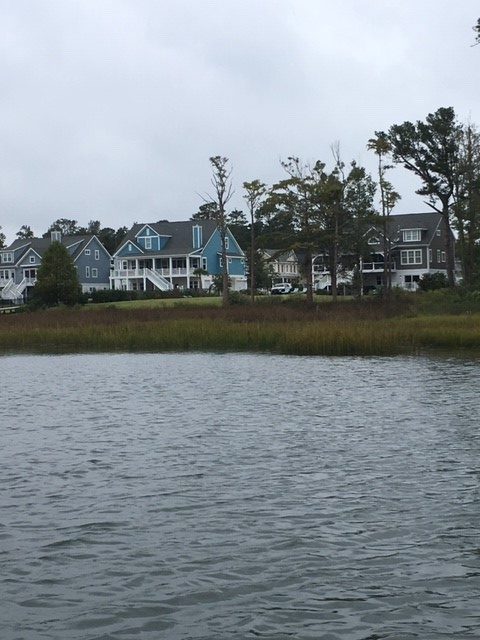

One, to be expected, was that, despite the clear dangers and mitigation challenges associated with a waterfront near the ocean in a region frequently affected by coastal storms and hurricanes, housing along Hewletts Creek remains attractive to its owners and has gained value as a result. These are people who love their boats and their access to the water, and the storms are simply part of the environment, much like a snowstorm in Chicago. Whether everyone takes all the appropriate precautions to protect those properties may be another matter, but most are at least aware of the challenges they face when hurricanes move toward North Carolina.

Because access to the water is a prized asset, most properties include piers, although shared piers are becoming more common, according to Glenn, presumably because of reduced costs and environmental impact. Those piers, however, have typically taken a beating in big storms, and Hurricane Florence contained some solid punches. One problem, he informed me, is that the buoyancy of the wood is the enemy of the piers’ survival because, as the storm surge rises and the piers rise with it, they are bent and twisted and collapse. In other words, the buoyancy of wood works against them. The photos provide ample evidence, but Glenn also told me that some had been repaired in recent months; if I had come three months earlier, the destruction would have been more evident. Past adaptation in some places was to rebuild the piers higher than before to move them above likely wave levels, but frequent storms and high storm surges have sometimes obviated the effectiveness of this approach. Instead, some pier owners are adapting with the use of Titan decking, which uses polypropylene plastic to stabilize the piers during future storms.

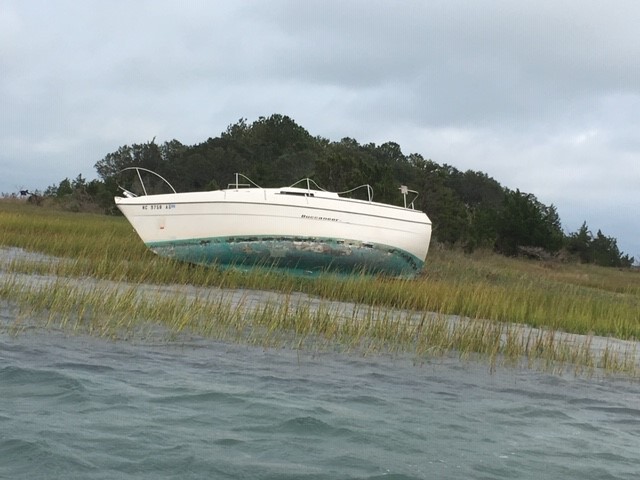

There were also, a year after Florence, remaining indications of the damages suffered to the boats themselves, which can easily be tossed about by winds and waves. We encountered one of those (below) toward the end of the tour.

It should be noted that, although it is inside Wilmington, Hewletts Creek has a much more rural or suburban feel than the Cape Fear River waterfront, which is near the urban heart of the city and its downtown. The riverfront is not primarily residential but encompasses a variety of commercial uses, including hotels and a large marina. In contrast, the waterfront along Hewletts Creek consisted predominantly of private residential property.

I do not wish to leave the impression from this glimpse of Hewletts Creek that what happened there is the extent of the impact of Florence. Although I did not have time on this trip to get a thorough tour of the city, I did receive other information from Glenn and from Christine Hughes, a senior planner with the city for Comprehensive Planning, Design, and Community Engagement. From her, I learned that Wilmington’s working and low-income populations sustained a large hit on their affordable housing stock with the loss of approximately 1,200 apartment units. In September, the Wilmington City Council approved $27 million worth of bond issuances for the Wilmington Housing Authority. A big part of that involved the closure of Market North Apartments on Darlington Avenue, which will be rebuilt. That closure forced evacuation by more than 1,000 residents. Wilmington will be recovering from Florence for some time to come. The cost and numbers of people affected in this housing redevelopment underscore the solemn fact that often low-income and minority populations suffer the greatest impacts of natural disasters. Our communities are not whole unless and until we give them high priority in recovery planning.

It is also worth knowing that the quest for coastal resilience is not new to Wilmington, which has engaged with federal and state agencies for some time, as illustrated in a 2013 report on a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency pilot project on community resilience. Glenn Harbeck has been in his current position for more than seven years after a long period of consulting and knows well the direction the city needs to take, but it is a long road. Residents can learn a great deal about the progress of infrastructure recovery projects from the city’s online map tracking such efforts, which include street and sidewalk repairs and stormwater management. Recovery is a complex process, as Wilmington knows well, and future storms, climate change, and sea level rise will all surely add to the challenges that lie ahead.

Jim Schwab