As a general rule, I am not about to tell people that the fate of the world depends on someone’s election to city council, even in a large city. On the other hand, some people climb the ladder to higher office after winning at local levels. But if candidates have commitment and staying power, one loss is unlikely to deter them in the long run. Barack Obama famously lost a Democratic primary election for Congress to U.S. Rep. Bobby Rush in Illinois’s First District in 2000, only to win a U.S. Senate seat by a landslide in 2004 and the presidency by a decisive margin against Sen. John McCain in 2008. People often learn vital campaign lessons from losing once or twice.

Meanwhile, aside from the question of who is positioned to run for higher office, most city council members, including aldermen in Chicago, have important jobs to do for their constituents. In Chicago, it is not a small job, as the city’s 50 wards average about 56,000 people, more than the population of all but a few suburbs. They are legislating for the third-largest city in the nation and handling constituent concerns about city services. Who holds these positions has some bearing on quality of life and civic satisfaction with city government. Collectively, the aldermen have considerable power and influence over property taxes, local environmental policy, land use, and development.

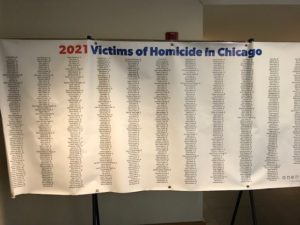

But this blog post is not a history or civics lesson. It is about the process of choosing these representatives who play a visible role in shaping the city’s future, and more importantly, about why participation matters. It is about the current Chicago election for mayor, other citywide offices, and 50 aldermen. In the bargain, Chicago is electing members of 22 new district councils that will work with the police department on law enforcement policy.

Chicago and all Illinois municipalities use a system created by the Illinois legislature in 1995 in which all candidates for local office run in a nonpartisan primary in late February. If any candidate for a particular office, such as alderman or mayor, wins an outright majority in the primary, that person is elected. If no one gets a majority, the top two vote-getters move on to a run-off five weeks later, and the winner takes office.

In Chicago, until 2011, either Richard M. Daley or Rahm Emmanuel won a majority overLori all other candidates and became mayor after the primary. Some wards had runoffs because no aldermanic candidate had a majority. That state of affairs ended in 2015, when Emmanuel, running for re-election, failed to win a majority and faced Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, now a member of Congress, in a runoff, winning against Garcia in a closer election than many people had thought likely. By 2019, the “old way” in Chicago was on its deathbed, with 14 candidates vying for mayor. Two African-American women, Cook County Board President Tony Preckwinkle and political newcomer Lori Lightfoot, a prominent lawyer and former federal prosecutor, led the vote, both with less than 20 percent. In a major voter rebellion against corruption, Lightfoot won the runoff with 73 percent of the vote, carrying every ward in the city. She became not only the first Black female mayor of Chicago, but the first lesbian mayor as well.

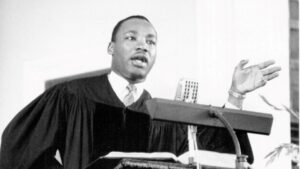

Daniel La Spata, Alderman, 1st Ward, City of Chicago. Photo from https://www.the1stward.com

The plethora of candidates was not limited, however, to the mayor’s race. Aldermanic races also saw far more entries than had been typical in the past. Progressive candidates became much more popular and prominent. In the 1st Ward, where I live, newcomer Daniel La Spata, a progressive with a city planning master’s degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago, uprooted incumbent Alderman Proco “Joe” Moreno by a 22 percent margin. Moreno was weighed down by a scandal after he was charged with filing a false police report and insurance claim after police stopped his girlfriend, who was driving his Audi A6. She told police he had lent the car to her. He had claimed the car was stolen. Later, out of office, he was again arrested after hitting numerous cars on a side street in Chicago’s Gold Coast late at night during what police said was a case of drunken driving.

I met La Spata during that campaign and liked him. I had a slight acquaintance with Moreno but was turned off by his legal problems. I felt La Spata offered an intelligent alternative at a time when the ward needed one. Over the past four years, I have had a number of opportunities to interact with La Spata. I found him responsive and thoughtful. In one email exchange, we discussed his advocacy in city council of increased availability of public restrooms, which are often scarce in Chicago. I pointed out that this was an issue not just for homeless persons who often lack access to such facilities, but for elderly people and those with disabilities or medical conditions that could make access an urgent need. I saw it as a public health issue. As a planner, I see public health as a serious local government responsibility that faces too many detractors—even without considering the controversy surrounding COVID-19 issues.

La Spata ran for re-election in the February 28 primary. He faced two political newcomers, Stephen “Andy” Schneider and Sam Royko, and Moreno, who was seeking a comeback. Royko, son of the late newspaper columnist Mike Royko, was a serious candidate driven by a concern about rising crime after his girlfriend was carjacked in the ward last year. Schneider is a community activist with a decent following. As for Moreno, I felt strongly that, while I believe in second chances, they do not need to involve public office after the sorts of problems he had created for himself. There are many other ways he can find to prove his commitment to the community without being entrusted with public office, and I suspect he will be able to find those opportunities. In any event, he garnered less than 7 percent of the vote, finishing fourth. It seems clear that the overwhelming majority of voters in the ward agreed with my assessment: Sorry, Joe, find another line of work.

The real question was whether La Spata or anyone else would win a majority on February 28. Knowing the outcome was less than certain, I volunteered, helping with his petition drive for ballot access. Aldermanic candidates need 750 signatures but often collect two or three times that number to ensure they have enough even after signature challenges by opponents, a common practice in Chicago. I spent one very chilly evening in November knocking on doors in the Logan Square neighborhood, not finding enough people home but adding slightly to the signature totals. During the campaign, I aided with phone calling on a Saturday but did less than I had planned closer to the election because of personal and family distractions. La Spata’s campaign staff was gracious about whatever time I could spare. He seemed to have enough volunteers to be highly competitive.

At one unfortunate point in the campaign, someone vandalized the La Spata campaign office. It remains unclear who did it, but a campaign organizer told me Schneider and Royko offered condolences and sympathies to La Spata over the situation. Democracy should function and thrive unimpaired by such behavior.

At one unfortunate point in the campaign, someone vandalized the La Spata campaign office. It remains unclear who did it, but a campaign organizer told me Schneider and Royko offered condolences and sympathies to La Spata over the situation. Democracy should function and thrive unimpaired by such behavior.

On election night, the importance of all that effort became clear. La Spata led the four-person field at one point with 49.44%, with Royko trailing with about half that number, and Schneider in third with less than 20 percent. La Spata appeared to be about 100 votes shy of a majority, although the numbers fluctuated through the evening. If that situation prevailed, Royko would face La Spata in a runoff.

But it is not as simple as it once was. More people vote early, more vote by mail, and all those ballots must be counted, systematically and precisely. By law, the Chicago Board of Elections must count all mail ballots that arrive within two weeks after the election, in this case, March 14, although they must be postmarked by Election Day, which was February 28. People who obtained mail ballots, which can be done by request to the board, can also turn them at early voting sites, which I did.

In the interest of full disclosure, I will note that my wife has served for several years as an election judge. I respect what these people do because I have watched her go to the nearby polling place the night before to set up, then retire early to wake at 4 a.m., arriving at the polling place by 5 a.m. to set up, not returning home until about 10 p.m. That is an exhausting day for a person of any age, let alone someone in her seventies, as we both are. Readers may fairly surmise that anyone wishing to question the honesty or integrity of election workers, as has become the fashion in many right-wing circles, will win no support or sympathy from me.

As the days followed, there was a noticeable drift in favor of La Spata as mail ballots were counted. La Spata jokingly referred to this situation as a “mail-biter.” This is not some mysterious or nefarious development, as former President Donald Trump might allege, but simply the process of allowing late-arriving ballots to be counted. The post office is not always efficient in delivering election-related mail. My wife had to visit the post office the previous Thursday in person to retrieve a bundle of undelivered mail that included the election board’s letter of authorization that she needed in order to pick up an equipment key from the board by that Saturday to fulfill her function as an election official. People’s ballots should be not be disenfranchised simply because the U.S. Postal Service does not always deliver mail in a timely manner.

By March 15, however, the die was cast. La Spata had exactly 15 more votes than needed to avoid an April 4 runoff, winning the primary outright with 50.11% of the total vote. In Chicago’s First Ward, every vote had mattered. Royko, who appears to have much to offer the community despite his loss, conceded quickly and congratulated La Spata. I hope they can cooperate and collaborate on issues important to the ward over the next four years. But it was also just as well to bring resolution to the contest.

As for the mayoral race, the world knows by now that Lightfoot did not survive her first challenge for re-election. Nine candidates competed, including Garcia, but the runoff this time belongs to two men, Paul Vallas, a frequent former candidate and former schools chief in not only Chicago but New Orleans and Philadelphia as well, and Brandon Johnson, an African-American Cook County Supervisor. Johnson began his career as a teacher and has strong ties to the Chicago Teachers Union, which often tangled with Mayor Lightfoot. Vallas has the support of the Fraternal Order of Police. Both candidates have other union endorsements. I will not comment further on that race, nor will I venture any predictions for April 4. Chicago, however, simply is no longer the machine-run city that Sam Royko’s father once wrote about in Boss, his famous biography of former Mayor Richard J. Daley, who died in office in December 1976.

Sometimes, things really do change.

And every vote really does matter.

Jim Schwab

Augustana Solar Project Announcement

Augustana Solar Project Announcement