It is Sunday evening as I start this blog post. Whether I finish it tonight is less important than simply getting it done. I had intended to get it done earlier, but other matters intervened, including a death in the family, so I am doing it now.

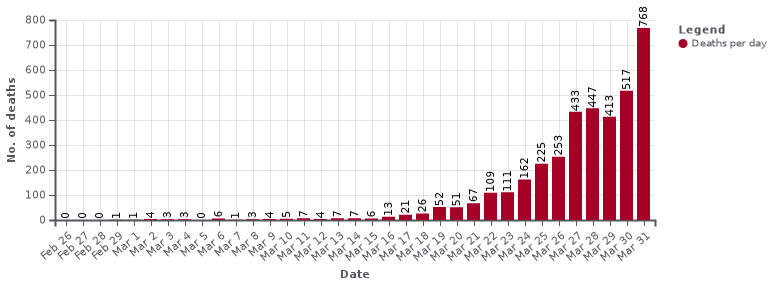

Part of my motivation is that I feel a small sense of empowerment from a successful start to a two-month series of Adult Forum discussions of climate change at my own church. I became the volunteer coordinator of the Adult Forum, which is the adult discussion group that meets during the Sunday school hour, in 2017, just in time for the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation. That is no small thing at a Lutheran church. Last week, introducing the moral and ethical questions surrounding the biggest existential question of our times—the radical environmental changes produced by humans in the industrial age—we had eight people in attendance, not  huge but remarkably good as church attendance struggles to regain traction after two years of pandemic lockdowns and fears of new waves of COVID. Our congregation has taken the pandemic seriously, and many of the elderly and the immunocompromised watch the weekly services online. This week, Adult Forum attendance grew to ten. Most people seem committed to the series. And they have lots of questions and paid rapt attention. I supplement what we do in our one-hour discussions with email distribution of links and attachments to additional material.

huge but remarkably good as church attendance struggles to regain traction after two years of pandemic lockdowns and fears of new waves of COVID. Our congregation has taken the pandemic seriously, and many of the elderly and the immunocompromised watch the weekly services online. This week, Adult Forum attendance grew to ten. Most people seem committed to the series. And they have lots of questions and paid rapt attention. I supplement what we do in our one-hour discussions with email distribution of links and attachments to additional material.

We started on the first Sunday by focusing on Katharine Hayhoe’s new book, Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World. My choice was deliberate. Before we tackled the science and the social and planning issues of climate change, it seemed important to consider how climate change became such a divisive issue for American society and the world. And there seemed no better place to start than with this excellent book.

Roots of Division

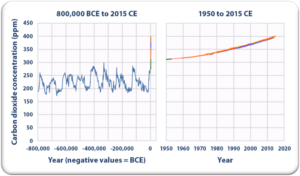

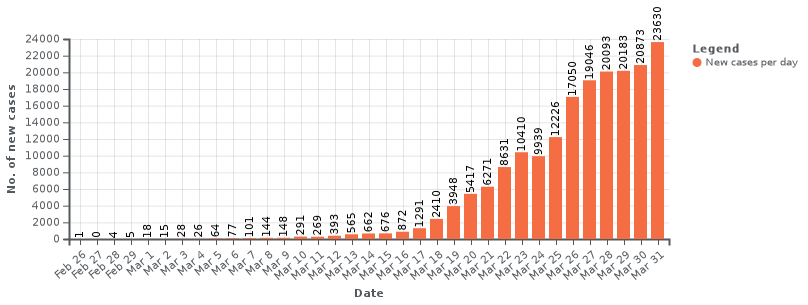

Why and how did climate change become such a divisive issue? Part of the answer is that climate simply became one of several issues that provided potent material for political polarization, which has also infected debates about racial justice, immigration, and a frequently paranoid distrust of science that has hampered efforts to address the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, the larger political environment swept climate change into the cauldron of this hostile partisan warfare. Consider the timing. Newt Gingrich’s right-wing uprising in the Republican party during the Clinton administration, a predecessor of the later Tea Party during the Obama administration, came along just as climate change was emerging as a topic of serious scientific debate. In due course,

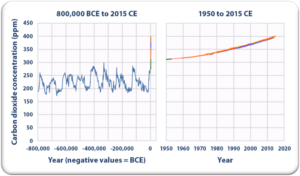

Source: US EPA

looking at the data, an overwhelming percentage of scientists in relevant fields came to accept the basic premise that human activities of the Industrial Age are the only credible cause of the warming effects we are seeing today, but the political discourse on the right largely dismissed the evidence. That discourse of dismissal was heavily supported by the fossil fuel industry and a public relations campaign to muddle the issue, a matter discussed in 2010 in the book by historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, Merchants of Doubt.

However, there is also the fact that climate change poses a long-term threat that many people find difficult to recognize as a more immediate crisis, at least before it is too late to reverse the damage. History is replete with examples of people failing in this way, and George Marshall, in Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change, published in 2014, explains why we are prone to disregard distant threats in favor of the problems immediately in front of us. Of course, in recent years, as evidence of the more visible and tangible impacts of climate change has accumulated, our attention to the larger problem has grown. But so, too, has the denial in some quarters, fueled in part by the growing distrust of science and scientists, who used to enjoy much higher regard in most quarters of modern society. But that was before they inherited the thankless task of explaining what Al Gore two decades ago called “the inconvenient truth.”

A Matter of Values

Katharine Hayhoe is one of those people who has found a mission in life. Such people are blessed because a positive mission, even or especially in the face of challenges, serves to help clarify one’s values. Hayhoe is clear about hers. An evangelical Christian from Canada, now working at Texas A&M University, she is committed to caring for the poor, the hungry, and the sick, but also to the truth, which means that, for her, facts matter. They matter greatly. She also likes to discuss what faith can teach us and how we communicate with each other in a civil and loving manner, something that is not always easily achieved. There are, in fact, times when the only option in a hostile conversation is to walk away.

The central point is to understand who we are and what we stand for as we undertake to persuade others not only that climate change exists and matters, but why it matters. And so, at the very outset, Hayhoe provides a chapter titled “Who I Am.” It is her suggested inventory of self-assessment:

- Where I Live

- What I Love Doing

- Where I’m From

- Those I Love

- What I Believe

- Be Who You Are

The underlying point, she stresses, is that people will care about climate change for different reasons, their own reasons. People, she notes, generally already have the values they need to care about the issue but often have not connected the dots. The only way those of who do care can help them connect the dots is by first inquiring about those values they share, and then listening. Without listening, we are largely talking past each other, which yields more tension than progress.

Photo from Shutterstock

As an example, she cites the day she spoke to the West Texas Rotary Club, whose banner declared “The Four-Way Test.” The test was, first, Is it the truth? Second, Is it fair to all concerned? Third, will it build goodwill and better friendships? And fourth, will it be beneficial to all concerned? She reports that she skipped the luncheon to spend the next 20 minutes reorganizing her presentation around those principles, noting, for example, that nearby Fort Hood, a military base, now draws 45 percent of its power from solar and wind, “saving taxpayers millions.” She won over some skeptics because, once they connected the dots, the whole proposition of confronting climate change became more meaningful in terms they understood and accepted.

Facts and Tribal Loyalties

“Facts are stubborn things,” President John Adams once wrote. They don’t bend to our preconceptions or political wishes. Nonetheless, people like to be able to choose the facts they embrace while ignoring those that fail to confirm their biases. To varying degrees, this probably describes all of us because human nature is seductive about illusions, but reality can be harsh when it asserts itself. The role of education is, in large part, to help us learn how to learn and, in the process, be willing to confront our biases. Learning is a life-long challenge.

One crucial bit of learning regarding opinions on climate change is that not everyone is on one side or the other. There is a spectrum between the polar opposites. While completing work on Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery: Next Generation several years ago, I discovered the work of two researchers, Tony Leiserowitz and Ed Maibach, who had produced a journal article titled “Global Warming’s Six Americas.” They systematically described six camps, or tribes, of people with different perspectives on climate change. Two, one on either end of the debate, corresponded with our common tendency to divide people into “pro” and “anti” factions. One, the Alarmed, are those who see a serious and near-term threat to the planet from climate change. Another, the Dismissives, reject any mention of climate change and are most likely to buy into conspiracy theories and misinformation.

But between them are four other groups:

- Concerned, who accept the premise of climate change but see the threat as less immediate;

- Cautious, who still need some convincing but are open to persuasion;

- Disengaged, who “know little and care less”; and

- Doubtful, who don’t see a serious risk.

I was pleasantly surprised that Hayhoe introduced their work in her first chapter, noting that the percentages of Alarmed had grown in the past decade, basically siphoning some numbers from the Concerned. The two groups combined form a narrow majority, while the Dismissives constitute about 7 percent. The percentage of Cautious had remained at about 20 percent.

The most important fact emerging from the survey work of Leiserowitz and Maibach is that those totally dismissing climate change as a reality are in fact a distinct minority. One conclusion that flows from that is that those working to educate the public on climate change have a large field to work with and can reasonably sidestep the Dismissives. Arguing or even talking with them is likely to prove a waste of time.

The Futility of Guilt

One approach that Hayhoe almost categorically rejects is laying guilt trips on individuals over consumer choices, in part because the tactic seldom includes a realistic assessment of the alternatives that people face in deciding how to live their lives and get things done. She particularly dislikes what she calls purity tests. For example, she notes that one British colleague questioned why she flew to a speaking engagement in Alberta instead of taking the train from Texas. The problem is that no such direct train route exists. Hayhoe calculated the time, hours, and expenses involved in even attempting this approach through roundabout scheduling and found, for one thing, that the miles involved in driving to Oklahoma City to catch a train east and north into Canada from New York City, in order then to use the Canadian rail system to cross the country from Toronto were enough to get her colleague from London to Irkutsk in Siberia. It would also take several days in each direction. It simply was not a practical option.

Many potential alternatives for reducing our carbon footprints must first be created through the political or economic system before individuals can be held accountable for failing to use them. In many parts of the country, people lack the ability to meet online efficiently because our nation has yet to make adequate or high-quality broadband available. One cannot use options that one does not have. People cannot be blamed for driving a car to a meeting in a location where mass transit is not available. It is small wonder that people often feel their efforts do not matter when they are faced with a paucity of individual consumer choices, especially when powerful forces have worked to ensure that more desirable choices cannot be implemented. Understanding this fundamental point is essential in recognizing why the debate over infrastructure policy is a debate about what future we wish to create for ourselves. Once upon a time, our nation chose to facilitate nationwide mobility by creating the interstate highway system. Today’s debate is in part about creating a network of charging stations that will make driving electric vehicles feasible for the average motorist. Societal choices dictate many individual choices, and focusing guilt on individuals is in most cases an exercise in futility. We could better spend that time moving mountains on Capitol Hill.

Why Everyone Matters

There is a great deal more to the book than I am recounting here, as is the case with almost any book that is well worth reading. The important conclusion Hayhoe offers, however, is one that should be common sense but suffers from a surfeit of wishful thinking. Basically, climate change is a situation wrought by humankind and, ultimately, fixable only by humans. Hayhoe makes clear that, in her belief system, it is illogical and irresponsible to expect God to intervene to solve the problem because God has given us agency to tackle problems of our own making. She quotes Proverbs: “Whoever sows injustice will reap calamity.”

Our failure lies in not realizing that we are simply subject to the rules of physics. Put another way—one perhaps more akin to Eastern philosophies–we have not aligned our lifestyles and social systems with a sound understanding of natural systems. As Hayhoe states, “If humans increase heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, the planet warms. Pretending we can defy physics by putting our heads in the sand or cultivating a positive attitude will merely keep us slightly happier until (and more surprised when) the axe falls.”

False hope is often fatal, and at the very least self-destructive. Hayhoe prefers rational hope, wherein we recognize risk and understand the stakes involved in the situation we have created, noting that this requires courage but also provides vision. Ultimately, vision is not simply some magical gift from the Almighty. It flows from the hard work of clarifying our goals and beliefs and acting on those beliefs. It is the hard but rewarding work of empowering the willing.

Jim Schwab

Augustana Solar Project Announcement

Augustana Solar Project Announcement