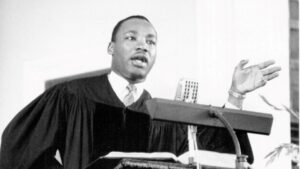

Holidays have a way of taming and diluting the real importance of the legacies and events they are meant to commemorate. This tendency is particularly true of today’s holiday celebrating the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. These efforts reflect some discomfort with the true level of sacrifice and commitment involved in fighting for freedom. Resisting this tendency requires some real thinking and soul-searching.

Holidays have a way of taming and diluting the real importance of the legacies and events they are meant to commemorate. This tendency is particularly true of today’s holiday celebrating the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. These efforts reflect some discomfort with the true level of sacrifice and commitment involved in fighting for freedom. Resisting this tendency requires some real thinking and soul-searching.

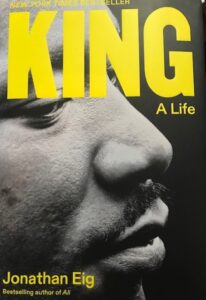

Sometimes, a very good author helps us regain some needed perspective on what matters. Fortunately, a few months ago, Jonathan Eig issued a new, deeply researched biography of King that helps us understand better not only what King did in his short life, but why he did it and what forces made him who he was. Admirably, Eig does not shy away from any of the ugly difficulties that kept King in danger throughout a 13-year ministry that began in 1955 at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. The son of Martin Luther King, Sr., who was then the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, outgrew his father’s legacy but also benefited enormously from his father’s self-made path from the son of Georgia sharecroppers to a prominent leader in the Black churches of the South.

Over the past two weeks, I have been leading a discussion of this remarkable book—King: A Life—in the Adult Forum of Augustana Lutheran Church of Hyde Park, in Chicago. The participation has been lively, and people have taken turns reading passages that I thought were especially illuminating. There is not room in one blog post to cover all that territory, so I highly recommend reading the book, but I will make what I think are some salient points about the King legacy.

Over the past two weeks, I have been leading a discussion of this remarkable book—King: A Life—in the Adult Forum of Augustana Lutheran Church of Hyde Park, in Chicago. The participation has been lively, and people have taken turns reading passages that I thought were especially illuminating. There is not room in one blog post to cover all that territory, so I highly recommend reading the book, but I will make what I think are some salient points about the King legacy.

First, I think it is hard for many people today, especially whites, to imagine the level of intimidation that racist thugs, including but hardly limited to the Ku Klux Klan, used in the post-Reconstruction South to suppress the Black vote, Black rights, Black dignity, and thus any semblance of true democracy. Eig relates one instance of family history in 1910, in which King’s ten-year-old father, then named Michael, was kicked by a white mill owner and sent home bleeding. His mother demanded to know who did that, then marched back to attack the mill owner with her own fists when he admitted doing this to her son. But her husband had to flee when a white mob arrived at their home. Black men who fought back, Eig notes, could pay with their lives.

The father remained bitter and became alcoholic even after returning home. King Sr., however, distilled the lesson that faith in God was the way out of that trap. He gained an education at Spelman College while working as a coal shoveler for a railroad company and became a preacher, ending up at Ebenezer. Later, in a 1934 visit to Germany, he was inspired by the legacy of Martin Luther to adopt that name in place of his birth name of Michael, and changed his son’s name, forever attaching the family to the legacy of the German religious reformer. Eig notes:

“He really related to Martin Luther,” said Isaac Newton Farris Jr., King’s grandson. “He had that same fighting spirit in him.”

His son would need that fighting spirit once he became the de facto and then real leader of the bus boycott that followed the arrest of Rosa Parks on December 1, 1955, in Montgomery for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger. Just four days later, King, at the invitation of other Black leaders in the city, gave a powerful speech to an overflow rally at the Holt Street Baptist Church that ignited the spirit of the Black community. It led thousands to spend the following year walking to work instead of riding the bus.

All that made King a huge target for an increasingly angry white community, or at least that large part of the white community that was resistant to justice. The White Citizens’ Council, which included police commissioner Clyde Sellers, claimed it grew from 800 members to nearly 14,000 as a result of the boycott. King was arrested and thrown in jail following a trivial traffic stop when he picked up Black passengers as part of an effort to provide rides for Black workers at designated carpool locations. Mayor Tacky Gayle had instructed police to tail and harass Black motorists who provided such rides. On January 30, 1956, while Coretta Scott King was hosting a friend at their home, they heard footsteps on the front porch, after which a bomb exploded, damaging the front of the house. King gave a speech that is remarkable for self-restraint while nonetheless demanding justice, instructing the crowd that assembled to “love your enemies” but also noting that he did not ask to lead the movement, but “if I am stopped this movement will not stop. If I am stopped, our work will not stop. For what we are doing is right, what we are doing is just. And God is with us.”

Reread those last five words, for I think they are key to what is often missing from people’s recollection of who King really was. How did he succeed in leading a successful nonviolent revolution for major social change in America? I think it is worth quoting a whole paragraph from Eig, in which he nails the point that is often missing from discussion of the King legacy, the fact that he was committed to a life of deep faith despite all his fears that his life could be cut short:

In years to come, journalists, historians, and biographers would speculate about what made King special, about what gave him the courage and vision to lead. Some observers have stressed the competitive nature of King’s relationship with his father. Other have focused on cultural factors, noting the guilt he felt about his middle-class upbringing and pointing out that he arrived in Montgomery when liberation battles were erupting in Africa and Asia and when radio and television made it possible for a brilliant young preacher to be seen and heard in millions of homes. But the Reverend James Lawson, one of King’s contemporaries, has argued that those interpretations miss an obvious and powerful explanation—that of King’s calling from God. “That was my case, that was King’s case,” Lawson said. “It’s not . . . boasting . . . it’s the deep-down-inside awareness that connects your life up with the life force of the universe, the God who created the heavens and the earth, to quote the Hebrew poets. So, anyone who has that kind of a calling, that’s something that profoundly alters their way of thinking and behavior.”

There is a great deal of depth and detail in Eig’s book. Last September, at the Harold Washington Public Library in Chicago, in a program co-sponsored by the Society of Midland Authors (Eig lives in Chicago), I had the pleasure of hearing Eig speak and relate how he got turned on to working on this biography. The very next day, I acquired the book at a local store. After a major surgery two weeks later, which I related in my January 1 blog post, I had ample recuperation time to tackle a long book. I immediately turned to this biography, plowing through it day after day in rapt fascination, thinking about how I would have faced the challenges in King’s life, which ultimately ended in his assassination at age 38 in Memphis in April of 1968, an event that triggered a wide range of reactions including, unfortunately, urban riots.

In those 13 years that followed his assignment, at age 25, as pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, he not only watched the world change, but helped change it. The bus boycott ended with an NAACP victory before the U.S. Supreme Court in Browder v. Gayle, which effectively outlawed segregation in intrastate transportation. Later, he would deliver the famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., watch as President Lyndon Johnson signed major civil rights and voting rights legislation, march in the face of insults and brickbats for fair housing in Chicago, and support the garbage workers strike in Memphis that ended with his assassination. Profoundly aware of his own fears, flaws, and shortcomings, his faith nonetheless bolstered his courage and helped him refashion American democracy in a way that still enriches us today, even when we face new domestic threats to its preservation.

It is critical that we get in touch with the roots of that courage, so that we do not squander all that was won at such a high cost. It is critical that we believe that God meant us to be so much better.

Jim Schwab