Wall art at the Peshtigo Fire Museum

Back on August 11, during a family vacation that involved circumnavigating the shores of Lake Michigan, my wife and I and two grandsons visited the small town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, and spent an afternoon at the Peshtigo Fire Museum. It is housed in a former church that the museum acquired in 1963. While there, I decided to purchase some items from the small gift shop near the front; the museum sells a handful of books and mementoes. One was a reprint of a special edition of a local newspaper that commemorated the 1871 fire that destroyed the town. The other was a small book by the Rev. Peter Pernin, a Roman Catholic priest who wrote about surviving the fire.

I may have acquired another item or two, but if I did, I have no proof. Planning to write this blog post on the 150th anniversary of the Peshtigo wildfire and the Great Chicago Fire, which both occurred on October 8, 1871, I wanted to read the items and discuss them here. Hours of searching my home office and the rest of our home turned up nothing. This is excessively unusual because I tend to be meticulous about keeping track of such acquisitions, but the anniversary approached and a maddening sense of futility took hold.

In frustration, I wrote to the museum through its online contact form and asked whether they could send me a new copy, and I have sent a $100 donation for their trouble. When I finally get a chance to read the material, sometime in coming weeks, I will supplement this post with a discussion of the historical materials. But before going on with the story, I want to commend the museum for a quick response from Wendy Kahl, who promised to send me replacements and expressed appreciation for the donation. I don’t remember the price of the items, paid in cash, but it was a fraction of my offering. The point, however, is that this small museum, in a small town in a rural area, is staffed by volunteers and operated on a shoestring by the Peshtigo Historical Society. They are, however, helping to preserve a vital piece of American history. Although I don’t often appeal for donations on this website, I will now. Those willing to help this humble enterprise can send donations to the Society at 400 Oconto Avenue, Peshtigo, Wisconsin 54157.

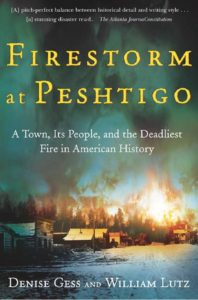

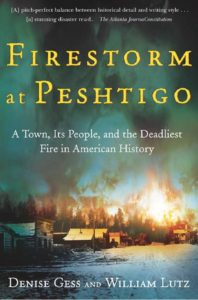

Most of us can gain only the tiniest inkling of the scale of loss suffered by a town like Peshtigo, which was a thriving lumber company town along the Peshtigo River near the shores of Green Bay, an arm of Lake Michigan, after the Civil War when catastrophe struck. I was about to write “when disaster struck,” but I quickly realized that the word “disaster” does not begin to do justice to the deadliest wildfire in American history. The extent of the devastation was so severe that no one really knows how many people died, but 1,500 or more seems to have become a reasonable estimate. The best narrative of the event I have read is Firestorm at Peshtigo by Denise Gess and William Lutz, published in 2002, but the museum website lists a few other resources.

Most of us can gain only the tiniest inkling of the scale of loss suffered by a town like Peshtigo, which was a thriving lumber company town along the Peshtigo River near the shores of Green Bay, an arm of Lake Michigan, after the Civil War when catastrophe struck. I was about to write “when disaster struck,” but I quickly realized that the word “disaster” does not begin to do justice to the deadliest wildfire in American history. The extent of the devastation was so severe that no one really knows how many people died, but 1,500 or more seems to have become a reasonable estimate. The best narrative of the event I have read is Firestorm at Peshtigo by Denise Gess and William Lutz, published in 2002, but the museum website lists a few other resources.

Those resources in total can do far more justice to the story than I can hope to do in a blog post. However, the point that I can make here is one that, curiously, seldom occurs, although it is clear enough in the book by Gess and Lutz: the organic connection between the two fires in Peshtigo and Chicago. Separated by more than 250 miles, it is not that their fires shared a proximate cause. That would clearly be impossible. Recently, syndicated Chicago Tribune columnist Clarence Page mused about theories propagated by Chicago-area writer Mel Waskin that meteors delivered the ignition while recognizing how far-fetched that sounds and confessing to his own belief in pure coincidence.

But one can rely on science while saying that the two fires on the same day were more than pure coincidence. The reality is that a hot, dry summer plagued the entire upper Midwest from Chicago to Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Minnesota. Such conditions are the natural breeding grounds for wildfire, as fire experts in California and Colorado have long known. During the long summer of 1871, note Gess and Lutz, various fires peppered the landscape from Lake Michigan to the Dakota Territory. Storms in Texas drove winds northeast to Michigan and Wisconsin. But, as we now understand, the conditions were ripe throughout the entire region for a much larger conflagration.

Photo of a burning building at the Peshtigo Fire Museum

And it came, a raging inferno that swept through more than 2,400 square miles of northern Wisconsin, literally destroying the small town of Peshtigo. One reason the Peshtigo Fire Museum struggles in some ways to tell the story is that so few of the town’s structures and valuables were left in any recognizable condition when the fire subsided: a pile of metal spoons forever fused together by heat, a badly charred Bible. Small wonder that much of the museum consists of other artifacts from the rebuilt town that are not really part of the fire story. It’s hard to populate a museum with what no longer exists and could never have been saved. But they can tell the story with what they know and with the paintings in which people reimagined the horrors they had faced.

There is another point, however, that is often ignored: Chicago and Peshtigo, economically and environmentally, were in those days joined at the hip. Peshtigo was essentially a company town, largely under the control of Chicago magnate William Butler Ogden, who owned a steam boat company, built the first railroad in Chicago, and served as the city’s first mayor. Ogden Avenue and a few other things in Chicago bear his name to this day. He was a legendary presence during the city’s first half-century.

In 1856, he also bought a sawmill in Peshtigo. The lumber industry was in high dudgeon in the upper Midwest in those days, shipping logs down rivers to Lake Michigan and down the lake to mills and yards in Chicago, where the new railroads could ship it to markets in the East and elsewhere. Chicago was a boom town with a dense downtown of largely wooden buildings, but the same milieu of sawdust and bone-dry lumber created the same conditions for a wildfire that existed in the northeastern corner of Wisconsin, just miles from the Michigan border. It is not clear that anyone knows definitively what actual sparks triggered the fires in each community, but the common ingredients of fuel, heat, and oxygen that power wildfires were clearly readily available in both cities at the same time, largely driven by commerce.

It is hard to imagine today how dangerous it all was. Even without a fire, logging was an inherently dangerous occupation, with many men maimed or felled by attempts to control rolling logs as they were corralled downriver to lake ports, or by trees that fell as they were being hewn (known ominously as “widow makers”) in a time that knew neither worker’s compensation funds nor work safety regulations. Expecting the owners of logging mills and lumber yards to understand the dangers of wildfire any more than they cared about reducing workplace injuries would have been unrealistic at the time, although a dawning awareness of the need for such regulation led to Wisconsin leading the progressive era with state-level reforms by the turn of the 20th century.

Aftermath of the fire, corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets, 1871. Reproduced from Wikipedia.

But for the many people who fled or succumbed to the fire on the fateful day of October 8, 1871, that was all in the distant future. The immediate reality is that many were burned alive, some died after jumping into the Peshtigo River to escape the flames, and thousands lost homes and all they owned in a matter of hours as the fire spread. Meanwhile, the same happened in Chicago, where 17,450 structures fell to flames that swept through a three-mile area in just three hours, including the supposedly fire-proof new headquarters of the Chicago Tribune. More than 100,000 people, one third of the city’s population at the time, were displaced from their homes. For weeks, the city lay in ruins as community leaders sought ways to finance and rebuild a city from the ashes. Chicago, of course, even then had far better access to capital and media attention than lowly Peshtigo, which remains a town with a population of just 3,500, some fifty miles north of Green Bay, the nearest city of even modest size.

Chicago’s media dominance, and its ability to retell its own story, continues. The Chicago Tribune, for instance, produced a commemorative special insert magazine, “The Great Rebuilding,” with a great deal of useful documentation. The Chicago History Museum opened its special exhibit on the fire today. But at long last, Chicago media outlets are also paying attention to their sister in tragedy with articles like the one in the Tribune describing at length “the fire you’ve never heard of.”

Chicago also had the resilience, although the term was not in common use, to conceive of rebuilding in a way that would avert future disaster. If you notice a lot of masonry construction on your next visit, you are seeing the legacy of the Great Chicago Fire, which altered local thinking about building codes and fire resistance. Similar shifts of thinking about structural fire safety, of course, occurred throughout urban America over the next half-century because structural fire was strikingly common at the time, and insurance companies and firefighters alike realized something had to change. But that may be a longer story for a future blog post.

The fires also fed our nascent understanding of the dynamics of wildfires and how they are influenced by weather, in the short term, and climate over longer periods. As Gess and Lutz note, the Peshtigo fire gave us the word “firestorm” as the result of a growing scientific recognition that the intense heat of a large wildfire can create its own weather within the conflagration, including tornado-like winds up to 90 miles per hour, caused by the differential between the heat of the fire and the cooler temperatures of the surrounding atmosphere. Tornadoes, of course, are born of such meteorological conflicts, an endemic condition of the vast interior of North America where colder northwestern winds meet in mortal combat with warmer winds from the Gulf of Mexico throughout the summer and into autumn. In commemorating the two fires, we can also recognize that they came at the dawn of an entire science of wildfires that is working against time today to catch up with the deleterious impacts of climate change.

History matters. And I hope that I have sparked more than a smidgeon of interest among readers in what I consider a deeply intriguing and intellectually challenging topic.

Jim Schwab