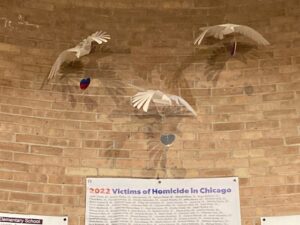

Candlelight vigil for the 10th Annual National Vigil for All Victims of Gun Violence. All photos provided by Kyle Duff.

On Friday, December 16, our grandson Angel was attending a biology lab class at Malcolm X College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago, where he is currently aiming to lay the foundation for a health care career. In his first quarter in college, he has not yet established the exact contours of that career. His world is still full of possibilities.

While he was in class, someone else’s life possibilities came to an abrupt close. The 36-year-old driver of a car moving down West Jackson Boulevard, right in front of the Malcolm X campus, slammed into a tree after being shot in what police say was a gang-related shooting. His 29-year-old female passenger was taken to a nearby hospital in critical condition, having also been shot. She later died as well. The campus was placed on lockdown as police cars descended on the area, establishing a crime scene investigation and collecting evidence. We learned about it initially from Angel in a phone call. I checked online to find out what had happened.

That evening, I watched for more news. After all, Malcolm X is near downtown Chicago and less than a mile from a training center for the Chicago Police Department, also on Jackson. It is just two blocks from the United Center, home of the Chicago Bulls and Chicago Blackhawks. It is near a major combination of hospitals, one affiliated with the University of Illinois at Chicago. On a Friday afternoon, this is a highly visible location.

But the event was superseded in journalistic importance that evening and in the next morning’s newspapers by a mass shooting at Benito Juarez High School that killed two students and wounded two others. To some, including this year’s Republican nominee for Illinois Governor, St. Sen. Darren Bailey, it probably helped justify his description during his recent losing campaign of Chicago as a “hellhole”—never mind Bailey’s long-standing opposition to gun control of all sorts. To others more aware of the larger social context, it provides more proof that the nation needs a better grip on the sale and ownership of firearms, including assault weapons. After all, Chicago is far from alone. In 2020 alone, more than 45,000 Americans died of gun-related injuries. Homicides from firearms have increased 14 percent over the past decade, while suicides by firearms have grown by 39 percent. We recently marked the tenth anniversary of the 2012 mass murder of dozens of children and teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. What we have is a nationwide epidemic, in which two shootings in one day in a large city like Chicago are an increasingly common occurrence.

These occurrences are among many reasons the voices supporting meaningful gun control legislation, including a ban on assault weapons, are rapidly growing louder and more insistent. In fact, just a week ago, on Sunday evening, December 11, Augustana Lutheran Church of Hyde Park, on Chicago’s South Side, hosted the 10th Annual National Vigil for All Victims of Gun Violence. With indoor and outdoor displays of the

These occurrences are among many reasons the voices supporting meaningful gun control legislation, including a ban on assault weapons, are rapidly growing louder and more insistent. In fact, just a week ago, on Sunday evening, December 11, Augustana Lutheran Church of Hyde Park, on Chicago’s South Side, hosted the 10th Annual National Vigil for All Victims of Gun Violence. With indoor and outdoor displays of the

names and faces of more than 630 people killed in Chicago this year, the gathering included a representative of Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, who missed the event due to illness, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL), and Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot, among others. Many of those attending were survivors of gun violence including relatives and friends of those whose portraits were on display. Many also represented or spoke on behalf of organizations of survivors such as Mothers of Murdered Sons and Chicago Survivors.

The issue, as has long been the case, is how to turn the pervasive, ongoing grief into action that matters in the face of an obnoxious and defiant gun lobby. It is not that gun owners do not have some legitimate rights and the right to air a point of view, but that  the leadership of the gun lobby has made so many so resistant to accepting facts or considering the impacts of their positions on thousands upon thousands of innocent victims. Their diversionary tactics, such as both Bailey and former President Trump painting Chicago as some sort of living hell (it is not; I live here and know otherwise) resulting from liberal values and hostility to police, are not only unhelpful but fail utterly to offer intelligent, evidence-based solutions to complex problems that are in no way aided by the free-flowing traffic of firearms across state borders and city limits. Say what they will, the mere fact that someone as troubled as Robert Crimo III was able to acquire both an Illinois Firearm Owner Identity (FOID) card and an assault weapon at the age of 19 is symptomatic of a gun culture that is blatantly out of control, and dozens of people attending a July 4 parade in Highland Park, Illinois, paid the price with their lives or with serious injuries. Yet the response of the gun lobby and its defenders fundamentally has been to double down on opposition to any reform of gun laws. Bailey, for instance, remains opposed to even having the state FOID requirement at all.

the leadership of the gun lobby has made so many so resistant to accepting facts or considering the impacts of their positions on thousands upon thousands of innocent victims. Their diversionary tactics, such as both Bailey and former President Trump painting Chicago as some sort of living hell (it is not; I live here and know otherwise) resulting from liberal values and hostility to police, are not only unhelpful but fail utterly to offer intelligent, evidence-based solutions to complex problems that are in no way aided by the free-flowing traffic of firearms across state borders and city limits. Say what they will, the mere fact that someone as troubled as Robert Crimo III was able to acquire both an Illinois Firearm Owner Identity (FOID) card and an assault weapon at the age of 19 is symptomatic of a gun culture that is blatantly out of control, and dozens of people attending a July 4 parade in Highland Park, Illinois, paid the price with their lives or with serious injuries. Yet the response of the gun lobby and its defenders fundamentally has been to double down on opposition to any reform of gun laws. Bailey, for instance, remains opposed to even having the state FOID requirement at all.

But the momentum is shifting, the tide is turning.

At the federal level, Congress finally acted this past summer by passing the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which has been signed into law by President Joe Biden. Among other provisions, many related to mental health services, it expands background checks on gun buyers under 21, provides funding support for state red flag laws, and restricts straw gun purchases. It authorizes $750 million over five years for crisis intervention programs. The Wikipedia article linked at the beginning of this paragraph contains a full list of other appropriations established in the law, and explains the law in greater detail. Click here for a full text of the law, which resulted from multiple compromises between Republican and Democratic senators. The law does not come close to solving all gun-related problems, nor is any law likely to do so, but it is a step forward.

In Illinois, as of this date, action is pending on the Protect Illinois Communities Act, which would ban assault weapons in the state. The bill got a committee hearing in Springfield the day after the vigil at Augustana Lutheran Church. Bridging a gap that has often concerned activists against gun violence, the hearing brought forth as witnesses not only Lauren Bennett of Highland Park, a relatively affluent North Shore suburb of Chicago, but Conttina Phillips, a victim of Halloween gun violence in Garfield Park, a predominantly Black and low-income neighborhood on the West Side of Chicago. While the bill aims to ban assault weapons, Phillips advocated for further action against other types of guns because assault weapons are only one factor in the gang-related violence afflicting Black and Latino neighborhoods.

Sponsored by State Rep. Bob Morgan (D-Deerfield), who marched in the July 4 parade in Highland Park and represents that district, the bill aims to ban the sale, manufacture, or delivery of assault weapons and other high-caliber firearms in Illinois and would require current owners of such weapons to register that ownership with the state. It would extend current red flag restrictions from six months to one year. It would also bar the acquisition of a FOID card for anyone under 21 unless they are active in the military. Pritzker just the week before the hearing had called upon the General Assembly to pass and send to him such a bill before the anniversary of the Highland Park shooting.

We can only hope. Well, actually, we can do more. We can lobby our legislators. We can speak out. We can attend rallies. We can make clear that such action and more is long overdue.

Jim Schwab