One of the long-standing questions concerning national disaster policy is why a state or community needs to suffer a presidentially declared disaster in order to be eligible for federal hazard mitigation grants to help improve its resilience against storms, floods, earthquakes, and wildfires, or other possible calamities. Ever since passage of the Stafford Act in 1988, most or all federal support for hazard mitigation projects has depended on a disaster happening first, which then triggered a spigot of grants for risk-reduction projects under the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). It was almost a perverse twist on the famous alleged Willie Sutton justification for robbing banks. Why suffer a major natural disaster? Because that’s where the money is.

But not necessarily any longer. FEMA’s new Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program is a major new source of money available on a competitive basis through applications from local governments seeking to reduce risk through hazard mitigation projects. Over the last two years, FEMA has shaped BRIC, responded to public and stakeholder feedback on its plans, and finally, released those plans earlier this summer, followed in early August by release of its Notice of Funding Opportunity for states and communities. Those jurisdictions can apply between late September and January 29, 2021, the deadline for submitting proposals. Importantly, the program continues FEMA’s decade-long march toward encouraging the integration of hazard mitigation planning throughout a community’s entire range of plans to ensure a more holistic approach with a better prospect of effective implementation. This policy dates back to a seminal 2010 report by the American Planning Association and beyond, but it is good to see it reinforced.

Breaking New Ground

BRIC began with provisions in the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (DRRA), passed by Congress in 2018 as part of a larger bill that primarily reauthorized the Federal Aviation Authority but included miscellaneous additional measures dealing with disaster policy and sports medicine. Of such bargaining are sausages made in the Capitol, but the specific provisions authorizing what FEMA chose to label BRIC were born of years of complaints and frustration among disaster professionals about sporadic and inconsistent federal funding for hazard mitigation projects before instead of after disasters. The Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 authorized a Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) program, but for the past two decades its funding has relied on the whims of Congress. In some years, that provided as little as $25 million for a national competition. Sometimes the threat of termination hung over the program. Such minuscule funding produced both inconsistent results and great uncertainty from year to year among potential grant recipients. Almost no one was happy with the program. BRIC now replaces PDM.

Under Section 1234 of DRRA, Congress authorized a new pre-disaster hazard mitigation grant program that would no longer rely on annual congressional allocations but instead will use an annual calculation of 6 percent of annual post-disaster funding for relief from presidentially declared disasters. FEMA will determine that number from estimates six months afterwards, and annually transfer those dollars into the BRIC fund. For Fiscal Year 2020, that will amount to $500 million, of which $33.6 million will be directly allocated to the 50 states, District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. A separate $20 million set-aside will fund tribal governments for BRIC grants. The remaining $446.4 million are available through the new national grant competition. That amount far exceeds any annual allocations from Congress for PDM. While DRRA states that this money is available to states with presidential disaster declarations in the previous seven years before a specific grant opportunity, in fact, all states and territories currently qualify under that criterion.

Antelope Valley flood reduction project, Lincoln, Nebraska

A FEMA fact sheet makes clear that BRIC also establishes new priorities for this assistance by providing incentives for:

- public infrastructure projects;

- projects that mitigate risk to one of more lifelines;

- projects that incorporate nature-based solutions; and

- adoption and enforcement of modern building codes.

I will return to these goals later in this post because all are important and some deserve further explanation. It is worth noting, however, that much of the new focus grew out of extensive stakeholder feedback as FEMA solicited input, and that feedback is documented in a separate FEMA report.

FEMA has also undertaken an extensive education effort to ensure that potential applicants are well informed on their options for grant proposals. The agency produced a series of five weekly one-hour webinars in July, some of which, in my opinion, are distinctly more informative than others. But their utility may vary with the existing knowledge and experience of those watching, so what is clear to me may be new to others. The best, again in my opinion, detail issues connected with the last three goals in the bullet list above. All were recorded and are available online.

Using BRIC Funds

The very first BRIC webinar spelled out the guiding principles for the new program, which are designed to support community capability and capacity building:

- encourage and enable innovation

- promote partnerships

- enable large infrastructure and projects

- maintain flexibility

- provide consistency

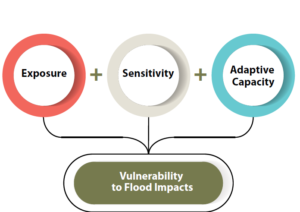

The clarity of priorities, focus on building local capacity for hazard mitigation, and streamlining of grant processes, among other factors, outline major differences from the previous PDM program, which suffered from inconsistencies that stemmed in large part from the erratic nature of its funding. The emphasis in selecting projects for support will turn toward their potential for risk reduction, innovation in planning and implementation, focus on addressing future climate, development, and demographic conditions, and support of community lifelines, among other factors as well as considering the types of populations affected by the projects and the partnerships and outreach outlined in the proposals.

Also important is that DRRA provided BRIC with a broad mandate for supporting the local adoption and enforcement of modernized building codes to better address protection against natural hazards. The new law also empowers FEMA to use BRIC to support technical assistance to communities, as well as reimbursing pre-award costs, that is, money expended for project development costs prior to grant approval, so long as the project is ultimately funded. Previously, communities could only use grant money for expenses incurred once the project had begun.

DRRA also expressed specific support for wildfire and wind hazard mitigation initiatives in Section 1205 and earthquake early warning systems in Section 1233. Projects addressing these types of mitigation will have clear support for BRIC funding approval as a result.

Building Codes

Section 1206 of DRRA addresses the need to provide stronger mitigation grant support for projects advancing the adoption of building codes that mitigate natural hazards. Codes adopted by local governments using BRIC grant support must conform to the latest published codes promulgated by organizations like the International Codes Council, which maintains a library of digital codes at the linked site. Permissible activities in this area under the BRIC guidelines include evaluation of the adoption or implementation of new codes in reducing risk; the enhancement of existing adopted codes; and the improvement of work force skills among the enforcement staff.

Building codes have assumed an increasing importance with the realization over many years of their cost-effectiveness in reducing losses. Despite residual resistance in some quarters to increased regulation through such codes, they are a clear asset in the hazard mitigation toolbox. The earthquake that struck Anchorage, Alaska, in November 2018 provided abundant illustration of the merits of mandatory building codes with dramatically shrunken damages compared to the 1964 earthquake that shattered much of the city. Likewise, experience in Florida has shown that stronger codes with adequate enforcement has driven down losses. Following the stark realities exposed by Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana adopted mandatory statewide building codes in 2006. Many other examples of improved building codes are readily available, pertaining not only to earthquake and hurricane wind damage but to wildfires and other hazards that can be mitigated through better building standards. Building and landscaping codes can be enhanced with design manuals and other outreach to builders and the public, such as the ignition-resistant design manual produced by the city of Colorado Springs, which has faced and learned from repeated wildfire events.

Grant applicants have other resources to which they can turn for information and support on building practices, including the BuildStrong Coalition, the Federal Alliance for Safe Homes (FLASH), and the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, a research entity supported by the insurance industry that includes test laboratories for determining the efficacy of various building materials and approaches. FEMA also has web-based resources on building codes.

Community and Infrastructure Lifelines

The concept of lifelines in a hazard mitigation context may be new to some, though the name itself is intuitively simple. Simply put, lifelines are important community services that exist to alleviate threats to life and property. Emergency managers have long used the term “critical facilities” to refer to those buildings and structures that must survive disaster impacts in order to provide continuous essential services such as transportation, public safety, shelter, and power to a community. But lifelines are more than physical assets; they are also systems that must be able to continue to function in an emergency or disaster. In BRIC, these are now the targets of focused mitigation projects, which can include efforts to strengthen and build the resilience of any systems and institutions within seven categories:

- safety and security;

- food, water, and shelter;

- health and medical;

- energy;

- communications;

- transportation;

- hazardous materials

FEMA introduced the concept of community lifelines in the fourth edition of the National Response Framework. The FEMA website includes a free download of its Community Lifelines Toolkit. Basically, the idea is to allow BRIC grants to support projects that reduce risk to these lifelines and help stabilize them quickly after a disaster occurs. These can include stormwater management projects, tsunami safety measures, infrastructure safety upgrades, and retrofits to essential buildings such as hospitals and shelters.

Nature-based Solutions

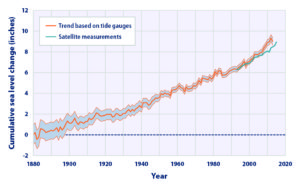

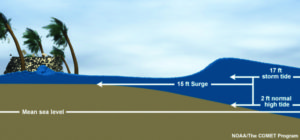

I will admit that, to me, some of the most intriguing initiatives within BRIC may focus on supporting green infrastructure, which is essentially what FEMA is labeling nature-based solutions. The central idea is to use the natural ecosystem services within a community or region to ameliorate the impacts of natural hazards by letting nature do what nature has always done best. FEMA has shown similar fascination with the concept by issuing a 30-page guide for local communities that outlines what these solutions can look like and how they function. These approaches have gained popularity in part as a response to climate change, but they are larger than that because they often address at least part of the problems associated with flooding and sea-level rise at less cost, often significantly less cost, than “gray” infrastructure or engineered structural solutions. In the final BRIC webinar, Sarah Murdock, Director of Climate Resilience Policy for The Nature Conservancy, noted that coastal wetlands had prevented an estimated $625 million in property damage during Hurricane Sandy. In various states

River restoration along St. Vrain River after 2013 Colorado floods

and cities, nature-based solutions have included green roofs, rain gardens, permeable pavements, living shorelines, and a growing array of other innovative design solutions to long-standing problems like stormwater management, urban heat islands, building energy demand, and urban flooding.

A great deal of research, case study documentation, and tool development has occurred in recent years with respect to nature-based solutions. For instance, Digital Coast, a program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, features tools such as the State of High Tide Flooding and Annual Outlook, the Climate Resilience Toolkit, and the Climate Explorer. NOAA also provides a variety of other technical assistance, for instance, through Regional Climate Centers and Sea Grant College Programs. Many states provide their own research and technical assistance, for example, through state climatologists, represented collectively the American Association of State Climatologists. Urban planners can access additional design ideas through the American Planning Association publication Green Infrastructure: A Landscape Approach. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has provided its own online atlas called Engineering with Nature that discusses the multiple benefits of these approaches. Finally, I would be remiss not to mention the stellar contribution of The Nature Conservancy with its web-based resource, Naturally Resilient Communities, an effort to which I can proudly claim to have contributed during my tenure at APA.

Outlook

The most promising feature of BRIC is that, because it was authorized by Congress in DRRA with a secure source of ongoing annual funding, it is not dependent on the shifting whims of presidential administrations. It has a solid chance of building an effective constituency among grant recipients pursuing projects that are highly likely over time to demonstrate their own worth so long as the program is administered with an eye to its goals and fundamental objectives. I am not trying here to be encyclopedic but to provide an entry point to the range of resources and possibilities that community applicants and advocates can use to ensure the success of BRIC. Given the steady rise in the costs of natural disasters, driven in part by climate change but also by demographic shifts and public policy decisions, making a difference by helping to drive down such costs is a national necessity. BRIC opens a new door toward wise investments to help achieve this goal. This nation needs some creative disaster problem solving backed by new resources.

Jim Schwab

Last Wednesday, December 2, the U.S. Senate passed the Digital Coast Act in a final vote that sent the legislation to President Trump for his signature. If that happens, it may provide a very useful gift to thousands of coastal communities wrestling with a wide variety of coastal zone management challenges.

Last Wednesday, December 2, the U.S. Senate passed the Digital Coast Act in a final vote that sent the legislation to President Trump for his signature. If that happens, it may provide a very useful gift to thousands of coastal communities wrestling with a wide variety of coastal zone management challenges.