GRATITUDE ON PARADE

#gratitudeonparade

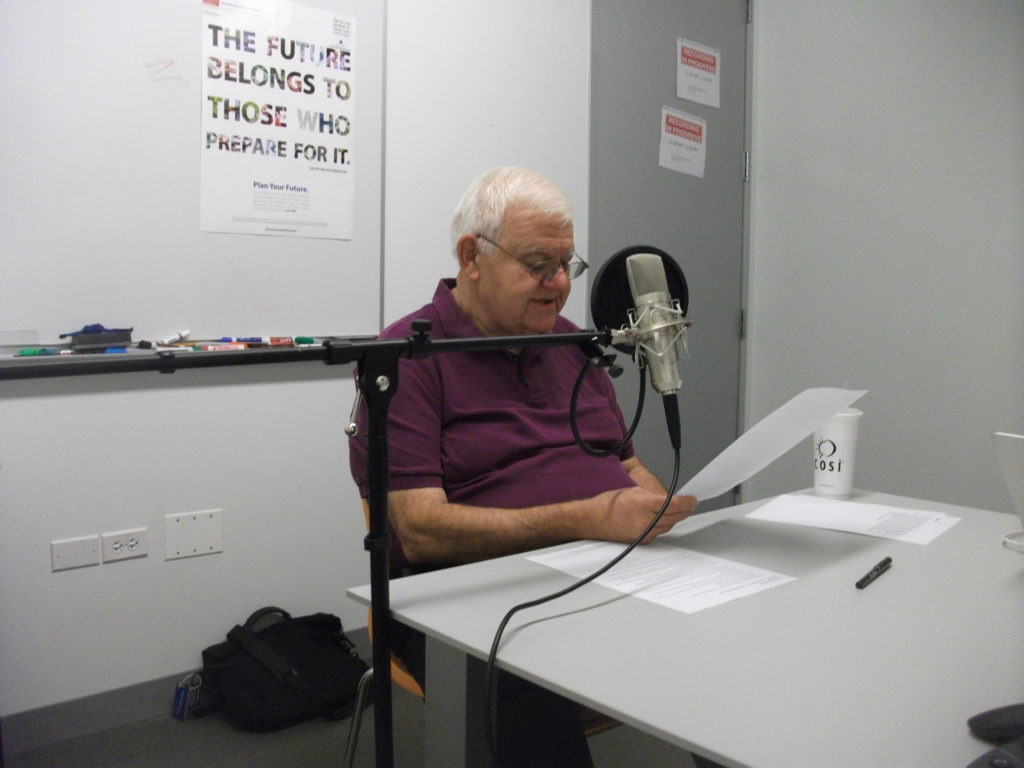

The size of the American Planning Association‘s loss when Stuart Meck departed can be measured easily by the size of Rutgers University‘s gain when he joined their staff, a fact immortalized by the Rutgers decision to name a lecture series after him. Marya Morris, who probably worked most closely with him at APA, got the opportunity recently to present the eulogy at the opening of that series. She shared some memorable stories, including his near death in the early 2000s when he was struck with an intestinal infection while they both were in Prague. It seems the Czech government felt it could learn a great deal about planning law reform by having Stuart Meck lead a 12-session workshop on the subject for high government officials. Pretty heady stuff.

I also worked with Stuart, though not as much as Marya. But we teamed up on hazard mitigation content for his pet project, funded by seven federal agencies and a few foundations, on statutory reform of state planning laws, known as Growing Smart. We also teamed up on a PAS Report, Planning for Wildfires. That may have been more in my wheelhouse, but trust me, Stuart was no slouch in mastering new topics and contributed very substantially to the final product.

Between all these major efforts, he found time incessantly to mentor the younger research staff at APA and was an indefatigable cheerleader for his profession. Did I mention he also co-authored a tome on Ohio Planning and Zoning Law? His productivity was a miracle to behold, as was his willingness to defend what he believed in. He died sooner than most of us who knew him would have liked, but he still deserves his day in the sun. The photos below, of various phases of his life, were provided by his daughter, Lindsay Meck. Thanks, Lindsay, for your help in this regard.

Posted to Facebook 2/10/2019

GRATITUDE ON PARADE

#gratitudeonparade

It’s been a couple of weeks, and I’ve been busy, but I have a great one today. I visited with Eugene Henry last Thursday and Friday while in Florida. On Friday, February 22, Gene’s dedication drove him across the state to West Palm Beach to hear my lecture for Florida Atlantic University on “Recovery and Resilience,” followed by a panel discussion and reception. Mind you, it’s a four-hour drive from Tampa.

But the day before, he hosted my wife and me on a personal day-long tour of Hillsborough County to show me the work they have done on hazard mitigation to reduce risks from hurricanes and floods. In a day or two, I plan to post a blog article on this subject, but Gene for some time has been the hazard mitigation program manager for Hillsborough County, a large urban area that includes Tampa. Gene is, as my friend Lincoln Walther, one of the panelists in West Palm Beach, said, “one of the best.” He has pushed the program forward, and he was a force behind the development of a very progressive Post-Disaster Redevelopment Plan that Hillsborough County pioneered several years ago. Gene is looking forward to retirement in a few years, but his contributions have been outstanding and deserve serious recognition. He is a true leader in the mitigation field. Let this tribute be a beginning, followed by the upcoming blog post.

Posted to Facebook 2/26/2019

GRATITUDE ON PARADE

#gratitudeonparade

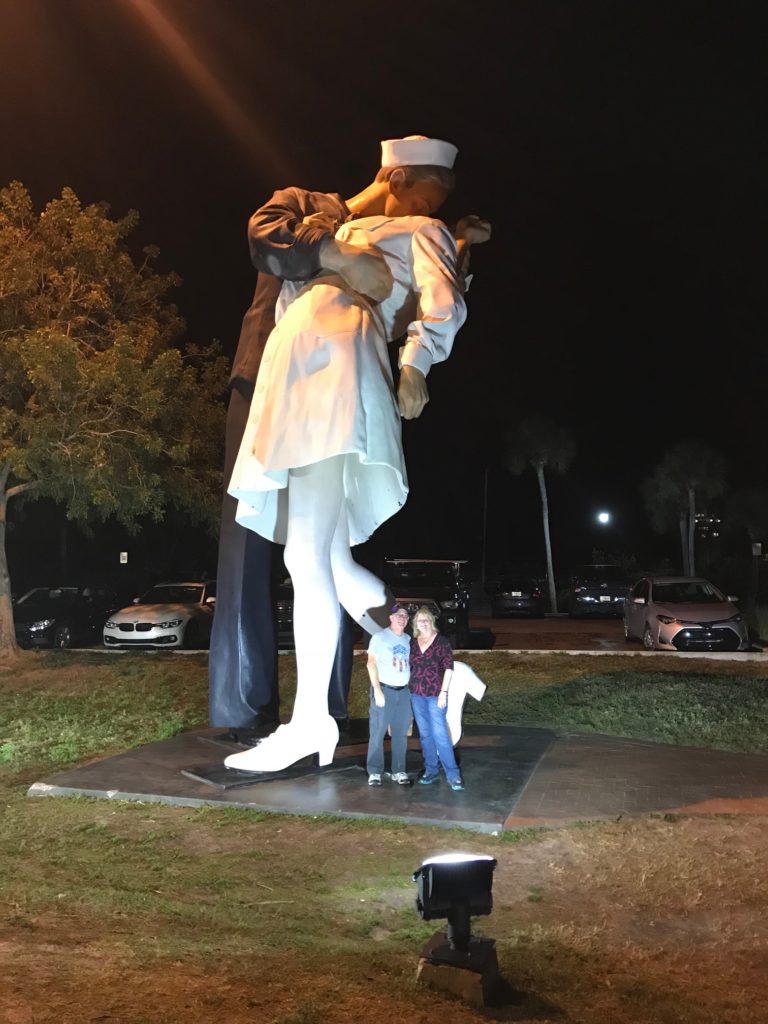

Today, I’d like to thank my long-time friend and high school classmate, David Taylor, and his wife, Linda, for their hospitality in sharing their home and time with us during our recent visit to Florida. David is the person who spurred me to come to Sarasota in the first place. He is also a photographer who used his resources, time, and energy, to film the entire two-hour program that I keynoted in West Palm Beach for Florida Atlantic University on February 22.

A Purple Heart Vietnam veteran, Dave is passionate about some subjects, including respect for veterans, and shared his stories with me and others about fighting his way back from serious injuries. He’s generous to the core but wise in his years. He was the emcee for our 50-year reunion last June in Brecksville, Ohio, for the Class of 1968. There is a lot I can say. He is currently taking film and history classes at State College of Florida with both students and professors younger than us, and enjoying it thoroughly because he has so much to share.

Most importantly, perhaps, he has gotten so excited about what he heard from listening to me that he wants to take all that talent and use it to help document disasters photographically, even as he gorges his brain on all that I have produced. Here’s to a good friend still finding his energy and a new mission in life as he nears 70.

The photo below? I cropped it to show him and Linda more closely, but the larger version, well, they’re standing under the Kissing Sailor statue in downtown Sarasota, which replicates that iconic photo from the end of WWII.

Posted to Facebook 2/27/2019

GRATITUDE ON PARADE

#gratitudeonparade

In the year after Hurricane Katrina, I met a young professor at University of New Orleans who was teaching transportation planning–John Renne. Soon, he had invited me to provide a closing keynote at a conference with a distinct theme: Carless Evacuation. Using a federal DOT grant, John was focusing attention on the central question of emergency management in the Big Easy: How do we move those people to safety who are the most vulnerable and lack independent transportation to just get out of town?

John has continued to raise vital questions like that ever since, even after moving in recent years to Florida Atlantic University. Florida faces plenty of its own questions concerning hurricane safety, and at 44, it would seem we can expect his contributions to keep coming. Recently, he and FAU hosted me to keynote a program on “Resilience and Recovery: Facing Disasters of the Future,” and I appreciated the chance to interact with planning professionals on what is known in Florida as the Treasure Coast. Bringing a hazards focus to transportation planning has been John’s unique and valuable asset not only regionally but nationally. FAU should be, and probably is, glad to have him.

In the photo below: Hank Savitch, Alka Sapat, myself, Lincoln Walther, John Renne. Hank, Alka, and Link joined me on the discussion panel that followed my talk in West Palm Beach a week ago. John was the moderator.

Posted to Facebook 3/2/2019