Where will we find badly needed leadership for climate adaptation?

Where will we find badly needed leadership for climate adaptation?

The United States, under President Trump, has withdrawn from the Paris climate accords. That does not, of course, eliminate the problem of climate change, but it does create a gaping leadership void regarding federal policy support for either mitigating climate change (by reducing greenhouse gas emissions) or adapting communities and businesses to better withstand its impacts. Many cities and some states have claimed the mantle of leadership by pledging continued efforts, and a few foundations have undertaken initiatives such as the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities. Newly emerging professional associations have emerged, notably the Urban Sustainability Directors Network and, perhaps most on point, the American Society of Adaptation Professionals. Other long-standing professional associations, such as the American Planning Association and the American Society of Civil Engineers, have weighed in on the subject, and even offered professional training, while maintaining their traditional focus.

But is all this activity a concerted push in the right direction? Or is it a growing babble of voices without strategic direction? Amid it all, is there an emerging field of practice for climate adaptation professionals, and if so, how well defined is that field? What credentials should it develop or require? These are no small questions because a great deal depends on the credibility of the scientific assessments made of the problem we must confront.

Kresge Foundation’s Climate Adaptation Influencers meeting in Washington, DC, January 22. Jim Schwab was a participant. Kresge Foundation photo.

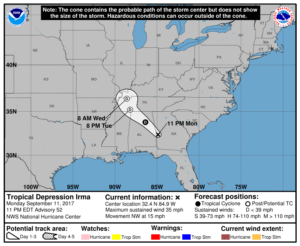

In that context, a new report from the Kresge Foundation, Rising to the Challenge, Together, is a welcome addition to the conversation, even as it stresses the urgency of both the conversation and our response to the problem. Given the steadily increasing toll of natural disasters and the increasing threat of sea level rise for coastal communities, high-precipitation storms for others, and prolonged drought and increased wildfire for many western and heartland regions, one can understand when the report, authored by Susanne C. Moser, Joyce Coffee, and Aleka Seville, states bluntly:

“The accelerating pace, all-encompassing scope, and global scale of climate change converging with other societal and environmental challenges—juxtaposed with the sheer difficulty of challenging and changing thinking, politics, and institutions to close the resilience gap—leave the field rather worried about the state of adaptation efforts in the US at this time. Some fields of practice have the luxury of evolving at their own pace; in the field of climate adaptation, failure or slow adaptation could mean death and destruction. Incremental progress in climate change simply does not match the rapidly accelerating pace of climate change.”

It is difficult for anyone well grounded in the science to argue with this sense of urgency. One is tempted to fall back on the nearly cliched image of the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland running to stay in place. But I’m not sure that image reflects the real urgency the Kresge report implies. A more appropriate image might be that of attempting to scale a mountain amid a landslide. That does not mean that I think the situation is hopeless. It does mean that the only solution may be to buckle our safety belts and rapidly grow our tenacity in confronting the perils that lie ahead. Tenacity is very different from panic. Later, the report states, “Crisis-driven adaptation has its limits.” Responding to crisis is reactive; tenacity requires vision. The problem, the authors note, is that the adaptation community has not yet defined a “vision for a desirable future.” What brave new world sits at the top of that mountain?

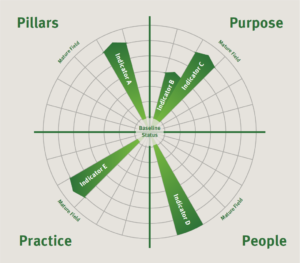

How Kresge survey respondents responded when asked to rate the status of selected sub-components of the adaptation field. All graphics provided by and reproduced with permission from Kresge Foundation.

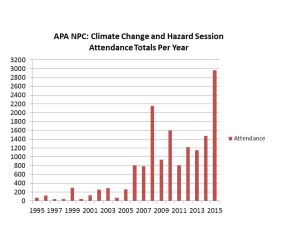

Attendance at climate-and disaster-related sessions at the APA National Planning Conference has risen dramatically over 20 years. Credit: Jim Schwab

There is an aspect of the emerging climate adaptation field that calls to mind the origins of both the urban planning and public health fields, which most people would describe as having the maturity that this new field seeks to achieve. Both responded to urgent health crises in rapidly growing modern cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Because of uncontrolled industrial pollution and poor sewage management, cities like Chicago, New York, and Baltimore were virtual petri dishes for disease. In time, both professions established positive visions for desired community outcomes, but those visions must now contend with the new threats climate adaptation aims to address. Thus, APA national and state conferences over the past two decades have seen dramatic shifts in content, with a greater emphasis on preserving those positive visions by addressing climate change and mitigating natural hazards. The Kresge report in its final chapter attempts to assess what the vision of a mature field of climate adaptation would be.

It is important, however, to understand the framework the report offers for the essential components of the climate adaptation (or any other) field of professional endeavor. Derived from lengthy interviews and surveys with study participants, including attendees at the 2017 National Adaptation Forum in St. Paul, Minnesota, Kresge offers what it calls “the 4 P’s.” These are:

- Purpose (why does this field need to exist?)

- People (who should be involved with what credentials?)

- Practice (how are best practices in this field identified?)

- Pillars (the public policy and funding support for the field)

This framing device may be one of the report’s most important contributions to thinking about the future leadership of the climate adaptation field. I would add that it is particularly important to see climate adaptation, much like its planning and public health forebears, as a field that is less about theory, although theory remains important, than about applied knowledge, which is almost inherent in the definition of adaptation. Unless adaptation is a matter of practice, the urgency the report discusses makes no sense. That said, one crucial skill planners may be able to contribute is synthesis. Planners may have their own unique set of skills and analytic methods, but they rely overwhelmingly on borrowing technical knowledge from the sciences, engineering, and economics to make sense of the urban organism and to help shape its future. Likewise, climate adaptation practitioners, while needing a solid knowledge base in climate science, will need to rely heavily on a bevy of other skills to succeed. Notable among these will be communication and people skills. Our communities will become hotbeds of climate progress only when the public is sold on both the nature of the problem and the feasibility of the solutions offered. The ability to facilitate that dialogue will be critical. Climbing that mountain will require pervasive public support.

The question of initiating effective dialogue with a public that is sometimes skeptical (location and timing matter here) feeds into another question raised in the Kresge report—whether it is more important to mainstream the concepts of climate adaptation or seek societal transformation with climate adaptation as a driving influence. Mainstreaming refers to the incorporation of climate adaptation concerns and practices into existing institutions and procedures. One major example would be hazard mitigation plans; another would be infusing such ideas into various elements of comprehensive plans, as well as regulatory tools such as zoning ordinances and building codes. Transformation, on the other hand, involves the pursuit of systemic changes in social and political structures. If there is to be a debate on this point, it seems to me the debate must be more one of emphasis than absolutes and should be context-sensitive. Transformation depends on situational opportunities tempered by foresight and the tenacious pursuit of a longer-term vision, but it does not rule out mainstreaming. Both approaches help to build more resilient communities for the future, but each may miss the mark if it is seen as the only valid perspective.

This is not an “either/or” choice but “both/and.” Because Kresge strives to maintain a social equity focus in climate adaptation discussions, I will point out that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was both a visionary and an effective tactician. One must know which matters most at a given moment. The report also mentions the tension between urban and rural perspectives and the potential for smaller communities being left behind in the quest for resources. Here lies a huge opportunity for transformational change, given the recent political divide. God bless the politician who can construct a connecting narrative that brings these forces together behind a progressive, scientifically informed agenda.

That leads to my final point before simply recommending that anyone with a serious interest in this field download and read the report. In its final chapter, the report takes note of the pressing need to build relationships across silos, to develop a common language and shared understanding of the problem, and to use a “whole community” approach to address problems. There is much more detail, but this is enough to suggest the drift. Climbing this mountain amid a landslide is no easy task. The details can be grinding and even discouraging when things do not go well. It is important to know how to measure progress and to keep the obstacles in perspective.

Planners, particularly, should know this. We are a profession of visionaries who know that details matter.

Jim Schwab