In two days, those who have not yet voted by mail or in person at an early voting site will have their last chance to express their views on America’s future. It is by far the starkest choice in my lifetime, and I will add that Harry Truman was in the White House when I was born. I have participated in presidential and other elections since 1972. The Twenty-sixth Amendment, which prohibited age discrimination in voting for those 18 and older, was ratified in 1971, while I was a junior in college. I have never taken that right for granted In five decades since then.

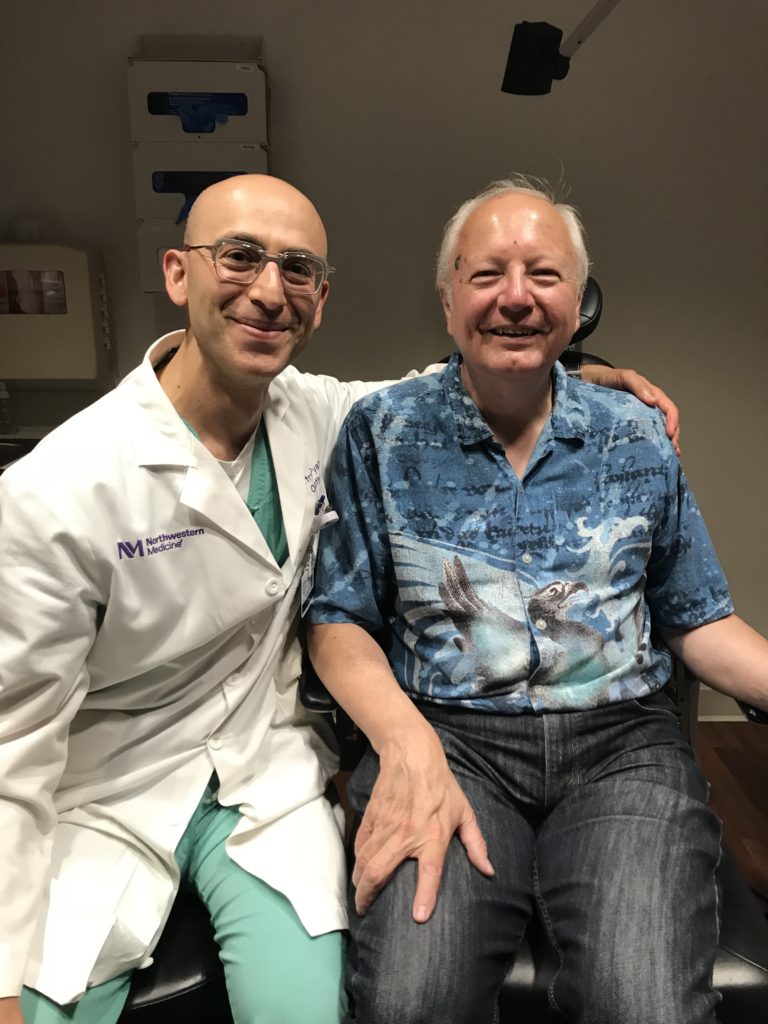

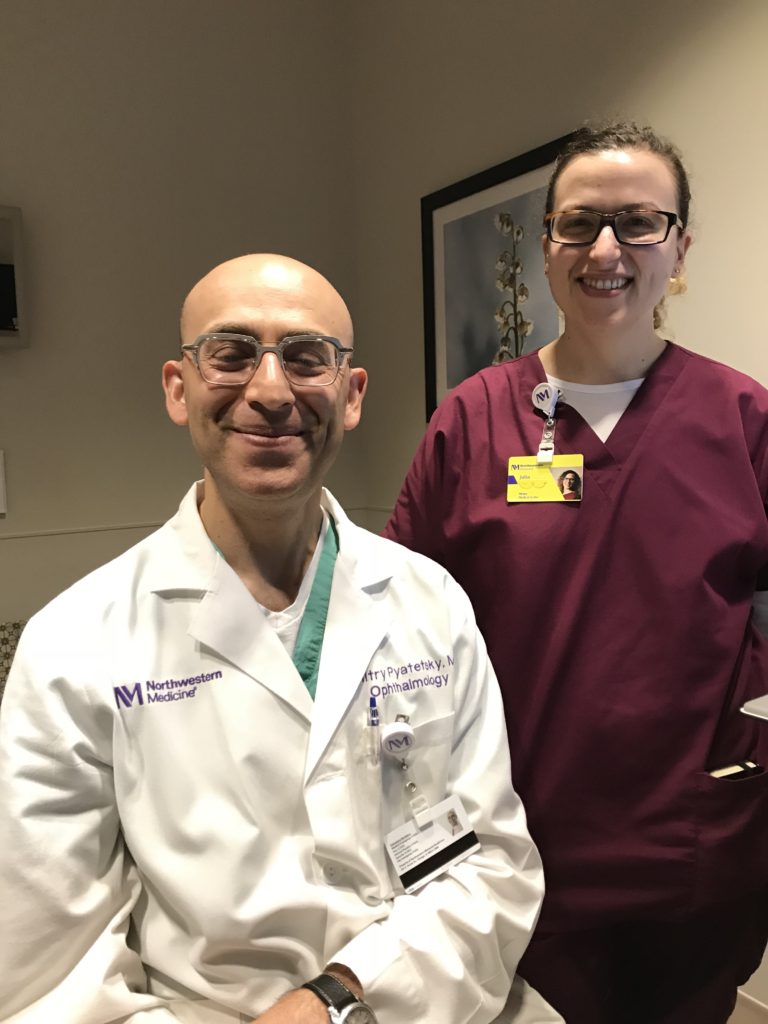

But I find it a curious coincidence that we face this choice in a year that can be pronounced Twenty-Twenty, the optometric formula for perfect vision. I first experienced the joy of 20/20 vision without glasses after my cataract surgery last year, so it has special meaning for me after growing up attached all day long to serious eyewear. But as I noted in my introductory blog post more than eight years ago, as a writer, scholar, parent, and student of life, I have also learned that 20/20 vision can be a metaphor for simply seeing the world clearly by sorting facts from fiction. It may thus be little surprise that, in a poetic post a few weeks ago, I used a hall of mirrors as the lens for viewing a current popular addiction to conspiratorial world views that have led many into the snare of our current U.S. president.

This is, first and foremost, an election about decency, honesty, and democratic norms. Simply put, one side observes them, and one side does not. I have never said that before about major party presidential candidates. Both sides have typically understood that a functioning democracy requires that standards exist that are not controverted, lines that are not crossed. Even Richard Nixon eventually acceded to such norms when he resigned the presidency in August 1974, following the Watergate scandal. Perhaps reluctantly, he acknowledged his own mistakes and shortcomings, and for the sake of the country left us all in the hands of Gerald Ford, a conservative but mainstream Republican who thoroughly embraced the need to respect institutional norms. When he, in turn, facing the headwinds of the era, lost a close election to Jimmy Carter, he conceded and moved on, as did Carter four years later. And so it has been throughout the vast majority of American history. Running for any office inherently entails the possibility of losing and accepting the verdict of the voters. I faced the same verdict myself In a city council election in Iowa City in 1983. Looking back, I can honestly say that, while raising some serious issues, I headlined a campaign that was less vigorous and convincing than it might have been. It was definitely a learning experience. Within two years, I was married in Omaha and found a job in Chicago. In a legitimate democracy, holding public office is a privilege, not an entitlement. Life moves on.

But apparently not for Donald Trump, for whom wealth and power seem an entitlement, and truth and honesty merely convenient fictions in a transactional lifestyle. Books exploring this megalomania, including one by his own niece, Mary L. Trump, have virtually become a cottage industry. I cannot think of another U.S. president whose own psyche has been the subject of so much close examination, hand-wringing, and concern about his grip on power—and I have read at least one biography of every single president in U.S. history. The problem is that Donald Trump is one of the least introspective presidents we have ever seen, and his obsessions are a legitimate source of concern.

Those fixations and projections have introduced elements into the present election that leadership skills alone, on the part of previous candidates, have suppressed for the public good. In 2008, John McCain notably rejected the efforts of some supporters to make race an issue against President Barack Obama. In 2000, despite a U.S. Supreme Court decision that many regarded as blatantly partisan and unfair, Vice President Al Gore, who had won the popular vote by about 500,000 votes, nonetheless sought to tamp down partisan anger for the sake of constitutional and institutional stability. Trump appears ready to do no one such favors. It is all about his ego.

Take, for example, his campaign’s ridiculous demand that a winner be declared on election night, viewed against a backdrop of baseless complaints about massive fraud in voting by mail (which I myself did this year, without a problem, to avoid being in a crowd amid a pandemic). This demand has absolutely no basis in American history, which is replete with instances in which it has taken well past midnight, and in 2000, several weeks, before a decision was clear. Even a modicum of reading in U.S. presidential history reveals, for instance, that in 1948, it was the morning after the election when the Chicago Tribune printed the famous headline, “Dewey Defeats Truman,” which Truman subsequently waved as a badge of honor when the final tally proved otherwise. In 1960, when John F. Kennedy won the popular vote by a razor-thin margin of 0.17 percent, Nixon did not concede until the following afternoon. These are hardly the only such cases.

However, before the era of television, the public rarely expected to learn the results on election night. This quick determination is a result not only of modern communications, but of the willingness of broadcasters to lure viewers with even the hint of making the first announcement of the apparent victor. What is different in 2020? Obviously, in a year of pandemic, early voting and mail-in ballots have far exceeded numbers seen in past elections; in Texas, such votes have already topped the entire voter turnout of 2016, perhaps because Texas is finally seen as competitive. Clearly, this high voter turnout is an indication that many more Americans have decided that the stakes are very high this year. But the false claims about fraud resonate with conspiracy-minded followers of the President, and combined with notable voter suppression tactics by several state Republican parties, they serve to undermine public confidence in the system to the advantage of no one but the incumbent. As I said, for Trump, it is all about Trump.

But it gets worse, as we have seen. By winking and laughing and refusing to insist that his own supporters observe at least the most basic democratic norms, Trump has enabled behavior that would be outrageous under any circumstances. For example, the Biden campaign was forced to cancel an event in Austin, Texas, when the campaign bus was surrounded on the highway by a caravan of dozens of cars of Trump supporters who slowed down in front of it, blocked its path, and in one case, rammed into an SUV belonging to a Biden staff member. Historian Eric Cervini, driving nearby, noted that the cars “outnumbered police 50-1.” This type of intimidation would have been both totally unacceptable as well as inconceivable in any campaign of the past. But not for Trump, who is probably amused. Where is his urgent call for law and order when his own supporters are the violators? Apparently, it is as ephemeral as it was after 14 men associated with a Michigan militia group were indicted on state and federal charges for plotting to kidnap the Michigan governor and put her on “trial” for what they imagined to be crimes related to protecting the public against the spread of COVID-19. Truly, we are operating in a funhouse reality when public health measures intended to save lives are viewed as crimes worthy of kidnapping and possible execution by vigilantes.

I could go on, but the point is already clear. Patriotic Republicans who still believe in democratic principles and in the value of American institutions of governance have already supported efforts like the Lincoln Project, which is backing Biden as the only means to return this nation to a semblance of sanity, in which presidents no longer mock science but listen carefully to experts and make reasoned decisions based on realistic perceptions of the threats to our nation’s health and security. One can be well-informed and skeptical of specific scientific findings, in part because science functions through a constant questioning and reanalysis to determine if inherited wisdom is sound or merits reexamination. As with everything from Joseph Lister’s development of sterility guidelines for surgery in the late 1800s to Albert Einstein’s theories concerning relativity to modern knowledge of the workings of DNA, that does not make science false. It is simply a process of making it better—far better than the silly ramblings of someone who would speculate about injecting disinfectants into the human body as a means of curing a coronavirus infection. We have huge challenges ahead in regaining our bearings on all these matters, and the fact is that the only viable alternative to Trump is former Vice President Joseph Biden, who benefits from long experience in the public sector and a healthy dose of humility, compassion, and empathy for his fellow human beings.

But I want to close on a special note for my friends and readers who may be independents or Republicans, or even Greens and Libertarians, or whatever other options may exist. I am not speaking here as a Democrat, although I will confess to that leaning. Throughout my life, especially in races below the presidency, I have been willing to cast aside partisan arguments to make independent judgments in cases where I felt specific public officials simply did not deserve my vote. This happened most often in cases of corruption, though ineptitude could also be a factor. I have, on occasion, voted for Republican and even third-party candidates when I felt the need to do so.

The most prominent example occurred in the 2006 gubernatorial election in Illinois. The tally would indicate that most Democrats supported Gov. Rob Blagojevich for re-election that year against Judy Baar Topinka, a Republican and former state treasurer. I had already begun to form a jaundiced view of Blagojevich’s infatuation with power and his own public image, and his frequent posing as a populist savior of the common man and woman. Something struck me as just plain wrong. In the end, I opted to vote for the Green Party candidate, but in retrospect, I should have just crossed the aisle to support Topinka, who was an honorable public servant. Disagreements on some issues were less important than a commitment to decency and honesty.

Subsequently, Blagojevich, following Obama’s ascent to the presidency, was charged and convicted on various charges of corruption, including an attempt to sell Obama’s seat in the U.S. Senate. He was impeached and removed from office by the Illinois legislature, and convicted by a federal jury and sent to prison. He is now out of prison because President Trump commuted his sentence, and as an act of gratitude, this Democrat who once appeared on The Apprentice is campaigning for Trump. Surprised? Not me. They are two peas in a pod. This year’s election is ultimately not about partisan affiliations but about public standards of behavior and decency in the White House. Which side are you on?

Harking back to my theme, this year is about viewing the options with 20/20 clarity. We can afford nothing less.

Jim Schwab