Like most people, I learned of the insurrection that resulted in five deaths and considerably more than 100 injuries to Capitol police from television news. Don’t ask me which channel; it was probably either CNN or MSNBC, but honestly, I don’t remember. I only remember what I saw—the searing image of American citizens attacking the seat of their own government on behalf of a President who lied to them because his twisted psyche did not allow him to admit that he had lost an election, fair and square. If he believes that the election was stolen, it is not because he has ever had any evidence to that effect. It is because he has repeated the lie to himself so often that he has internalized it completely. Such men are very dangerous.

There are plenty of good, well-written commentaries on the events of January 6, and it is not my aim to add another broad assessment of the day. The testimony before, and the final report of, the House Select Committee will add immensely to our knowledge, but it remains to be seen whether it can change minds. Even in 1974, as Richard Nixon was about to resign the presidency after a visit by a delegation of distinguished Republican Senators convinced him the gig was up, about one-quarter of the American public still sided with him, either disregarding or disbelieving the criminality on display from the Watergate affair. Even the most venal and corrupt politicians have always had their supporters, often until the bitter end. It is not as if the larger public is composed entirely of angels, after all. When the support fades, it is usually because the politician in question is no longer useful.

Corrupt and authoritarian politicians are almost always bullies who are highly skilled at making offers that their followers, and often others, cannot refuse. There is nothing new about this phenomenon. It is as old as civilization itself. The Bible is replete with evidence of such venality, dating back thousands of years.

So, what do I have to offer?

On the afternoon of the insurrection, I was preparing for a pair of sequential consulting meetings when the news caught my attention. That led to a mercifully brief text exchange with someone I will leave unidentified. I will paraphrase for clarity while sharing its essence. The point is not who it is, but his perceptions in the face of what effectively was a coup attempt. I understood his politics for many years beforehand; sometimes, he would needle me about it, and sometimes in recent years I was forced to terminate a conversation that, in my view, had departed earth’s orbit and no longer made sense.

But at that moment, I had to believe even this riot, insurrection, coup attempt, call if what you will, would be too much even for him. I was wrong.

I asked if he was still happy with Trump after Trump had incited an insurrection at the Capitol.

I was told that, after years of corruption that no one had challenged, except for Trump in the previous four years, “people are fed up.”

I want to step back here and make two points about this expression of frustration.

First, regarding corruption, this is a vague term that, without specifics, can be used as a broad brush against almost anything one disagrees with, and I believe that was happening here. There is, in my view, little question that corruption has at times affected both political parties. Personally, I have been perfectly willing to cross party lines to vote against candidates and office holders with documented records of corruption of any kind. I intensely dislike politicians who put self-interest ahead of the public interest. I am also aware that my disagreement with their policies does not constitute evidence of their corruption. Those are two different things, and we need to respect that difference if democracy is going to involve any kind of principled debate about what is best for our society. There are times when those lines are blurred, and times when it is clear. For instance, I was pleased last year when Democrats in the Illinois House of Representatives voted to replace long-time Speaker Michael Madigan, who had become entangled in a corruption scandal involving Commonwealth Edison Co. and its parent Exelon, with Chris Welch, who became the first Black Speaker in Illinois history. Welch may not be perfect either, but it was time for Madigan to leave. He has retired into obscurity, but he may yet face federal charges. I could name dozens of such situations in either party.

But to suggest that no one had addressed such corruption until Trump did so is ludicrous. It also demonstrates a willful blindness to facts. The litany of evidence of Trump’s shady transactions in both business and politics is overwhelming, from the $25 million fraud settlement in the lawsuit against Trump University, to the tax and insurance fraud charges now being brought against the Trump Organization by the Manhattan District Attorney, to the investigation of Trump’s demand of Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find” enough votes to allow Trump to claim victory in that state in the 2020 election—the details have filled multiple books over many years. No matter the depth of evidence that Trump not only does not fight corruption, but personifies it, followers will insist on dismissing such evidence, almost surely without ever reviewing it. Nonetheless, it is absolutely clear to anyone reading all this, as I have, that Trump has never been the weapon against this corruption that this complaint suggests.

For those who may think otherwise, or want to better arm themselves to discuss this topic, I include a short, incomplete bibliography of Trump-related investigative literature at the end of this blog post. Beware: It may keep you occupied for weeks.

But there is also the claim that “people are fed up.” This deserves closer analysis. One could ask, Fed up with what, exactly? My correspondent cited Biden “bringing back old retreads that Obama had in his cabinet.” That is hardly a crime, of course, and may well have indicated a preference by a new president facing a crisis of confidence in government for choosing experienced people who know how to make government work. That is hardly cause for a riot, let alone a coup attempt, and I said as much, though admittedly I may have sparked further anger in referring to the corruption claims as a “bullshit excuse” for an insurrection—especially since the express purpose was to prevent certification of the election. He also noted the need for better trade agreements, for someone to “actually help the working person,” and the loss of manufacturing jobs. I would readily agree that these are all legitimate political issues, subject to debate both on the streets and in the media, and in Congress and state legislatures, but justification for an insurrection?

That was the red line I could not cross, nor could I accept that anyone else should be allowed to do so.

The idea that all this frustration, not all of it based on accurate perceptions, justified an attempt to overthrow an election underlines a sense of civic privilege that I find appalling. If your preferred candidate failed to make his case to the American people—and that is precisely what happened to Trump—it does not follow that the only path forward is insurrection. The presumption behind this logic is deeply rooted in white privilege, even if its advocates do not wish to consciously own that brutal truth.

After all, if anyone is entitled to a sense that they are pushing back against persistent injustice, it would be African Americans, who can cite centuries of brutal suppression and slavery prior to the Civil War, the use of home-grown terrorism through organizations like the Ku Klux Klan to suppress Black voting rights and citizenship and economic opportunity, Jim Crow laws that enforced inequality well into the 20th century, vicious housing discrimination, and violent police actions, such as those of the Alabama state troopers who assaulted peaceful demonstrators in Selma in 1965, all of which make pro-Trump protesters’ allegations of unfairness pale in comparison. Yet, most African American citizens have persisted across centuries to use what levers they have within the democratic system to achieve a more equitable society. Admittedly, there are times when tensions have boiled over, but who could reasonably have expected otherwise? I am not justifying violence, but asking reasonable people to consider the disappointments to which Black Americans have been subjected for generations before making comparisons to the complaints of the MAGA crowd.

Moreover, such issues of delayed justice have affected other minorities, such as Chinese, the subject of an immigration exclusion law for decades, the Japanese internment during World War II, and widespread prejudice and discrimination against Latino immigrants over the past century. One could go on, but the point is clear. All have sought doggedly to work through the existing system to resolve injustice.

That leads to the next element of the exchange, in which I insisted that any Democrat instigating such an attack would be accused of treason, and that to react otherwise to Trump’s insurrection is “blatant hypocrisy.” I wanted to draw direct attention to the double standard that was being applied by many Republicans in this instance. In fact, I added, “Coup attempt is crime.” Democrats made similar allegations, of course, in the second impeachment trial.

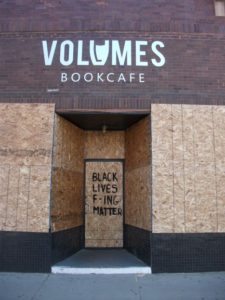

That led to the countercharge that Democrats were hypocritical in allowing “looting, burning, shooting and harassing of innocent people” in the demonstrations and riots that followed the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in the summer of 2020. He then referred to Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot as “part of the elitist liberal problem in this country.” As with the corruption issue, we were back to the broad-brush approach to asserting problems without specifics.

At that point, I decided to end the conversation because it seemed clear that the discussion was going to veer off track. I made clear that “I have never endorsed violence and I never will.” But I added that in Trump’s case, “This is an official condoning this,” which separated it from mayors who did not like the violence in their cities, but were faced with challenges in deciding the best approach to handling it. His comments also ignored the fact that 93 percent of Black Lives Matter protests were completely peaceful. I contrasted such practical policy decisions to “federal crimes encouraged by a US president who should know better.” And with that, the exchange ended.

I realize, of course, that this is just one such conversation among millions of exchanges among friends and relatives with contrasting views across the country. I did not completely disagree with all of his concerns, but I also was deeply puzzled as to how those of us worried about the future of democracy when it is under attack by followers of a demagogue like Trump can wrestle with jello or shadow-box with phantoms, given the vague and disingenuous statements with which we are confronted, including some of his.

In the meantime, speaking of stealing elections, we are watching some amazing voting rights shenanigans, to say nothing of phony “audits,” at the state level. What will we say when the second insurrection anniversary rolls around? Will anything have changed?

Partial Bibliography: Recent Books on President Donald Trump and/or the Insurrection

Johnston, David Cay. The Big Cheat: How Donald Trump Fleeced America and Enriched Himself and His Family. Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Karl, Jonathan. Betrayal. Dutton, 2021.

Leonnig, Carol, and Philip Rucker. A Very Stable Genius. Penguin Press, 2020.

Leonnig & Rucker. I Alone Can Fix It. Penguin Press, 2021.

Raskin, Jamie. Unthinkable: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy. Harper, 2022.

Schiff, Adam. Midnight in Washington: How We Almost Lost Our Democracy and Still Could. Random House, 2021.

Woodward, Bob, and Robert Costa. Peril. Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Woolf, Michael. Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House. Little Brown, 2018.

Jim Schwab