Sylvia Vargas and Ben Carlisle present FAICP medallion and certificate in Phoenix. Photo by Joe Szurszewski; copyright by American Planning Association.

Sometimes we find ourselves on a journey whose significance is bigger than the meaning for our own lives alone. In fact, if we are lucky, we come to realize that we can make at least some part of our lives much bigger than ourselves. Two weeks ago, while in Phoenix, being inducted into the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Certified Planners (AICP), one of the highest honors in the profession of urban planning, it became very apparent to me that I was not accepting this honor just for myself. I was also doing it for hundreds of other planners, if not thousands, who have incorporated disaster recovery and hazard mitigation priorities into their careers as essential parts of the ethical duty of planners to help promote public safety. Collectively, our work saves lives, reduces property damage, and reduces many of the negative impacts of human activities on the planetary environment.

Before I go farther in discussing those impacts, let me provide some context for the majority of readers who are not professional planners. AICP is a designation currently held by at least 15,000 professionals who have taken a certification exam, eligibility for which is based on a combination of education and experience. Most common these days as a starting point is a Master’s degree in urban planning, but there are other entry points, and there are undergraduate degrees in planning as well. AICP members, who are also members of the American Planning Association (APA), which has about 38,000 members, must maintain their status through a minimum of 32 hours of continuing education every two years, including 1.5 hours each of legal and ethical training. Only after a minimum of 15 years in AICP are planners eligible for consideration, through a rigorous review of their accomplishments and biography, for acceptance as fellows (FAICP). Only about 500 people have ever been inducted as fellows, including 61 in this year’s biennial ceremony, the largest group to date. I had the honor of being included in the class of 2016.

The very formal ceremony introduces each new fellow individually in alphabetical order while a member of the AICP review committee reads a 100-word summary of his or her achievements, during which the fellow receives a pin, a bemedaled ribbon, and certificate. Mine described my work as “pivotal” in incorporating natural hazards into the routine work of urban planners. That pivotal work is the point of my discussion that follows.

I did not start my work in urban planning with any focus on disasters, except perhaps the industrial variety. I did have an intense focus 30 years ago on environmental planning and wrote about issues like farmland preservation, Superfund, waste disposal, and other aspects of environmental protection. My first two books focused, in order, on the farm credit crisis of the 1980s and the environmental justice movement, the latter published by Sierra Club Books. I have joked in recent years, sometimes in public presentations, that even with that environmental focus in my academic training at the University of Iowa in urban and regional planning, I don’t recall ever hearing the words “flood,” “hazard,” or “disaster” once in all my classes. But I did hear about wetlands, air quality, water quality, and similar concerns. Frankly, in the early 1980s, natural hazards were simply not on the radar screen as a primary professional concern for any but a mere handful of planners. Even the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) came into being only in 1979, and these issues were seen largely as the purview of emergency managers. There certainly was no significant subdiscipline within planning devoted to hazards.

It was 1992 when Bill Klein, then the research director for APA, asked me to take over project management for an upcoming cooperative agreement with FEMA to examine planning for post-disaster recovery. As a preliminary step to this work, he sent me on a trip to south Florida for the APA Florida Chapter conference in October 1992 in Miami following Hurricane Andrew. Two aspects of that trip made a lasting impression. First was the keynote delivered by Bob Sheets, then the director of the National Hurricane Center. At one point, he showed a slide on the huge screen at the front end of the ballroom. It was an aerial photo of damage on two sides of a highway, with one side showing only modest damage and the other massive damage with roofs torn off and homes destroyed. There was no differential in wind patterns, he said, that could explain such differences at such small distances. The only plausible explanation, he insisted, lay in differences in the quality of enforcement of building codes. Florida then had stricter building codes than the rest of the nation for wind resistance, but they only mattered if code enforcement was consistent. Here, it was clear to me, was a problem directly related to development regulations. The second involved a field trip aboard several buses for interested planners to south Dade County. At one point I saw that the roof of a shopping center had been peeled off by the winds. It nearly took my breath away. Then our buses got caught in a traffic jam at the end of the afternoon. The cause was a long line of trucks hauling storm debris to landfills. This was already two months after Andrew.

Under the agreement, we didn’t start work on the project until October 1, 1993. In the meantime, floods had swept the Upper Midwest, making parts or all of nine states presidential disaster declaration zones. I decided to jump the gun on our start date and visit Iowa while it still was under water. Local planning departments in Iowa City and Des Moines cooperated in showing me their cities and sharing what had happened. It turned out that I was undertaking this project, in which I engaged several veteran planners to help write case studies and other material, at the beginning of America’s first big decade of disasters. (The next was even bigger.) In 1994, the Northridge earthquake struck the Los Angeles area. In 1996, Hurricane Fran struck North Carolina, followed by Hurricane Floyd in 1999. In the meantime, not only had our report, Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery and Reconstruction, been published in 1998, but so was another report of which I was the sole author: Planning and Zoning for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations. Floyd left much of eastern North Carolina, liberally sprinkled with poultry and hog feedlots as a result of regulatory exemptions, devastated, with hundreds of thousands of animal carcasses floating downstream. Eventually, they were burned in mobile incinerators introduced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Suddenly, it became apparent to me that the environmental concerns aroused by such operations and the impacts of natural disasters were thoroughly intermingled. Bad public policy was exacerbating the impact of disasters like hurricanes and floods.

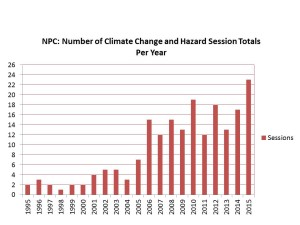

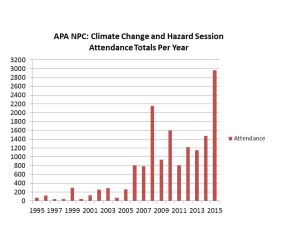

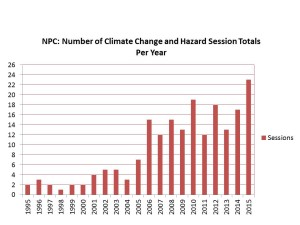

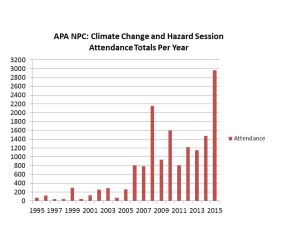

At this point, I need to make clear how low the level of engagement was back then between professional planners and disaster issues. In 1995, the APA National Planning Conference, which in recent years has typically attracted about 5,000 registrants, included two sessions related to disasters, at which the total attendance was 73 people. Disasters were anything but the topic du jour. Yet the events of that decade made clear, at least to me, that something had to change in that regard.

What I did not anticipate, based on past experience, was how quickly that would happen. For one thing, the Planning Advisory Service (PAS) Report grew on people and became a classic in the planning field. By 2005, after Hurricane Katrina, APA published a new edition, and FEMA made boxes of them readily available in the Gulf Coast, with planners like Stephen Villavaso, then the president of APA’s Louisiana chapter, voluntarily driving through stricken towns and passing out copies to local officials. In the meantime, I had worked on several other hazard-related projects addressing planning for landslides and wildfires and providing training on local hazard mitigation planning, among other efforts. After the APA conference in New Orleans in 2001, a group formed and continued to meet over dinner at every subsequent conference that billed itself as the “Disaster Planners Dinner,” an event that has become the subject of some legends among its veterans. The growing contingent of planners taking hazards seriously as a focus of their professional responsibilities was growing quickly and steadily.

Hurricane Katrina, more than any other event, added a powerful new element to the public discussion. It made crystal clear to the national news media that planning mattered in relation to disasters, and because of that perception, they called APA. Paul Farmer, then the CEO and executive director, and I shared those calls, and I logged no fewer than 40 major interviews in the two months following the event in late August 2005. I stressed that disasters involve the collision of the built environment with utterly natural events, and the resulting damage is not an “act of God” but the outcome of human decisions on what we build, where we build it, and how we build it. Planners have the responsibility to explain the consequences of those choices to communities and their elected officials during the development process, and those choices sometimes have huge social justice impacts. Katrina cost more than 1,800 lives on the Gulf Coast, most of them involving the poor and the physically disadvantaged. Better planning thus became a moral imperative. Making that perception stick produced a sea change in public understanding of the high stakes involved.

That afforded me considerable leverage to win funding for new projects with FEMA and other entities, most notably including the 2010 publication of Hazard Mitigation: Integrating Best Practices into Planning, a PAS Report that argued strongly for making hazard mitigation an essential element of all aspects of local planning practice, from visioning to comprehensive planning to policy implementation tools like zoning and subdivision regulations. Now the focus of a growing amount of federal and state guidance in this arena, that report was followed in 2014 with a massive update and revision of the post-disaster report, Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery: Next Generation, which dissected the whole process of long-term community recovery from disasters and argued fervently for pre-disaster planning to set the stage for effective recovery and resilience after an event. Those efforts came under the umbrella of the Hazards Planning Center (HPC), created by APA in 2008 along with two other centers as part of the National Centers for Planning. I have been the manager since HPC’s inception, and I was happy. We had succeeded in institutionalizing within the profession what had once been treated as a marginal concern of planners.

Along the way, that dinner group grew, attracting dozens of attendees by the end of the decade, and becoming large enough and attracting enough petition signatures to become APA’s newest membership division in 2015, the Hazard Mitigation and Disaster Recovery Planning Division. They now meet as such during the APA conferences. They are no longer an informal group. They are official and at last count had at least 250 paid members. But the interest is far larger. Remember those numbers from the 1995 APA conference? In Seattle at the 2015 APA conference, almost 3,000 people attended 23 different sessions related to climate change and natural hazards. I was the opening speaker for the very first session in the climate track, and the room was full. There was an overflow crowd in the hall outside. Hazards and climate change adaptation had arrived as a primary concern of planners. A growing number of graduate schools of planning, including the University of Iowa, where I have been adjunct faculty since 2008, now include curricula on such topics.

This bar graph and the one below were developed last year for a presentation I did in July 2015 at the opening plenary of the 40th annual Natural Hazards Workshop, in Broomfield, Colorado.

I want to state that, although I often had only one intern working with me at APA, I have never been a one-man show. On most of those projects, I involved colleagues outside the APA staff as expert contributors and invited many more to symposia to help define issues. Those APA sessions attract numerous speakers with all sorts of valuable experience and expertise to share. This is a movement, and I have simply been lucky to have the opportunity to drive the train within the APA framework as the head of the Center.

The night after the FAICP induction, at their division reception, members of the new APA division jokingly award me an “F” to go with my AICP. Alongside me is Barry Hokanson, HMDR chairman.

So let me take this story back to that moment two weeks ago when I walked on stage and accepted induction into FAICP. Before, during, and after that event, I received congratulations from many colleagues intensely interested in hazards planning, and I realized I was not simply accepting this honor for myself. My achievement was theirs too, and was literally impossible without them.

“You’ve gone from fringe to mainstream,” my colleague Jason Jordan told me the opening night of the Phoenix conference. He ought to know. Jason is the experienced governmental affairs director for APA and has a keen sense of the trends in planning and of government policy toward planning. But in order for his statement to be true, one important thing had to happen: Lots of other planners had to climb aboard that train for the journey. My success in winning this honor was symbolic for them, in that it served to validate the value of their commitment. I did not get there alone. A growing army of planners who care about public safety and community resilience helped make it happen, and I shall always be grateful—for them as well as for myself.

Jim Schwab

What makes a community stronger and more resilient in the face of severe weather threats and disasters? Clearly, preparation, awareness of existing and potential problems, and a willingness to confront harsh realities and solve problems are among the answers. Can we bottle any of that for those communities still trying to find the keys to resilience? Perhaps not, but we can share many of the success stories some communities have produced and hope that the knowledge is disseminated.

What makes a community stronger and more resilient in the face of severe weather threats and disasters? Clearly, preparation, awareness of existing and potential problems, and a willingness to confront harsh realities and solve problems are among the answers. Can we bottle any of that for those communities still trying to find the keys to resilience? Perhaps not, but we can share many of the success stories some communities have produced and hope that the knowledge is disseminated.