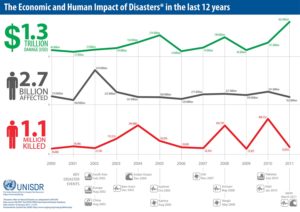

For some time, it has been my intent to address the question of how we communicate about and discuss climate change, with a focus on books that have tackled the issue of how to explain the issue. Several of these have crossed my desk in the last few years, and I have found some time to read most. These include: Climate Myths: The Campaign Against Climate Science, by John J. Berger (Northbrae Books, 2013), and America’s Climate Century, by Rob Hogg (2013). The latter, independently published, is the work of a State Senator from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, inspired by the ordeal his city underwent as a result of the 2008 floods. I met Hogg while serving on a plenary panel for the Iowa APA conference in October 2013 with Dr. Gerald Galloway, now a professor at the University of Maryland, but formerly with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers when he led a major federal study of the causes and consequences of the 1993 Midwest floods.

Another book that made it into my collection but still awaits reading is Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change, by George Marshall (Bloomsbury, 2014), an English environmentalist. To him and the others, I apologize. Many good ideas for blog posts went by the boards in past years when my occupational responsibilities at the American Planning Association sometimes kept me too busy to implement them. Whether it is still worthwhile to go back and review these works of past years is debatable, but at least I offer them up here as contributions to the literature. It is critical that we keep revisiting the issue of climate communication because, clearly, much previous communication has failed in the face of determined efforts by skeptics to sow doubt and uncertainty, to the point where the U.S. now has a president who has withdrawn the nation from the Paris climate accords, a subject I addressed here a month ago. It is imperative that we find better ways to share with people what matters most.

From https://www.climateofhope.com/

As a result, I was overjoyed to see two heavyweight voices, Michael Bloomberg and Carl Pope, offer what I consider a serious, well-focused discussion in their own brand new book, Climate of Hope: How Cities, Businesses, and Citizens Can Save the Planet (St. Martin’s Press, 2017). Bloomberg, of course, is the billionaire entrepreneur of his own media and financial services firm, Bloomberg L.P. I confess I read Bloomberg Business Week consistently because it is one business magazine that I find offers a balanced, thoughtful analysis of business events. Carl Pope, former executive director of the Sierra Club, is an environmental veteran with a keen eye to the more realistic political opportunities and strategies available to that movement and to those anxious to address the problems created by climate change. Theirs is an ideal pairing of talents and perspectives to offer a credible way forward.

This book will not seek to overwhelm you, even inadvertently, with the kind of daunting picture of our global future that leaves many people despondent. At the risk of offending some, I would venture that the most extreme and poorly considered pitches about climate change have nearly pirated for the Earth itself Dante’s line from The Inferno: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” I know one person who literally suggests something close to that. I fail to see where that sort of message leads us. The harsh political and social reality is that most people need to understand how something they can do will make some concrete difference that may make their lives better now as well as perhaps a half-century from now. There are temporal factors in human consciousness that greatly affect how we receive messages, and most of us are not well programmed to respond to issues too distant in time or in space. Framing the message effectively matters.

The bond that brings these two authors together is that combination of hope and realism. They may understand that polar bears are losing their habitats, but their message focuses closer to home: Business opportunities await those willing to embrace solutions to climate change. Cities can make themselves more livable even as they reduce their negative impacts on the atmosphere. Despondency is not only counterproductive; it is downright pointless in the face of such golden eggs waiting to hatch. This is more than rhetoric. Climate of Hope provides a steady diet of details for investing in solutions, whether through public policy and programs such as Bloomberg highlights in New York and other cities, or in the business sector, which both authors do very well.

Of course, there are some very tough questions that must be addressed. The biggest involves the future of energy both in the United States and around the world. In a chapter titled “Coal’s Toll,” Bloomberg is unflinching after crediting Pope and the Sierra Club for bringing to his attention the public health costs of continued reliance on coal. He notes that pollution from coal emissions “was prematurely killing 13,200 Americans a year,” or 36 per day because of various lung and respiratory diseases, with a resultant financial toll exceeding $100 billion annually. In many other parts of the world, the figures are even higher. All this is in addition to the environmental damage of lost and polluted creeks and rivers wherever coal is mined or burned. To counter this toll, the Sierra Club, with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies, undertook a campaign to close outdated coal-fired power plants. It is also important to recognize the degree to which fossil fuel companies have benefited from public subsidies and relaxed regulation that has failed to account for the magnitude of negative externalities associated with coal and petroleum.

Inevitably, someone will ask, what about the jobs? The strength of Bloomberg in this debate is his understanding of markets, and he rightly notes that, for the most part, coal is losing ground because of the steady advance of less polluting, and increasingly less expensive, alternatives including not only natural gas but a variety of new energy technologies like wind turbines, energy-efficient LED lights, and electronic innovations that make coal essentially obsolete. The issue, as I have noted before in this blog, is not saving coal jobs but investing in alternative job development for those areas most affected. Once upon a time, the federal government created a Tennessee Valley Authority to provide economic hope and vision for a desperately poor region. Although the TVA or something like it could certainly be reconfigured to serve that mission today, the federal vision seems to be lacking. Instead, we get backward-looking rhetoric that merely prolongs the problem and makes our day of reckoning more problematic.

It is also essential to balance the problems of coal against the opportunities to shape a more positive, environmentally friendly energy future. In many parts of the world, off-grid solar can replace more polluting but less capital-intensive fuels like kerosene or wood for cooking. Hundreds of millions of poor people in India and other developing countries could be afforded the opportunity to bypass the centralized electrical facilities of the West through low-cost loans to build solar networks. Again, what may be missing is the vision of world banking institutions, but under the encouragement of international climate agreements, and with the proper technical support, places like India can make major contributions to reducing their own greenhouse gas output. The U.S. expenditures in this regard about which Trump complained in his announcement of the U.S. withdrawal from the climate accord are in fact investments in our own climate health as well as future trade opportunities. In chapter after chapter, Bloomberg and Pope describe these opportunities for private investment and more creative public policy. The intelligent reader soon gets the idea. This is no time for despair; it is instead a golden day for rolling up our sleeves and investing in and crafting a better future.

It is possible, but probably not desirable, for this review to roll on with one example after another. We face tough questions, such as reshaping the human diet to reduce the environmental and climatic impacts of meat and rice production in the form of methane, but there are answers, and Pope explores them in a chapter about the influence of food on climate. Food waste is a source of heat-trapping methane. Both en route to our plates and after we scrape them off, food waste can be a major contributor to our problems because of decomposition, but again there are answers. The issue is not whether we can solve problems but whether we are willing to focus on doing so. There will be disruption in the markets in many instances, but disruption creates new opportunities. We need to reexamine how the transportation systems in our cities affect the climate, but we should do so in the knowledge that innovative transit solutions can make huge positive impacts. We can reframe our thinking to realize that urban density is an ally, not an enemy, of the environment, when planned wisely. Urban dwellers, contrary to what many believe, generally have much lighter environmental footprints than their rural and suburban neighbors. They ride mass transit more, bicycle more, and mow less grass. Lifestyles matter, where we live matters, planning matters.

Quality of life in our cities is a function, however, of forward-looking public policy. Bloomberg notes the huge changes being made in Beijing to reduce its horrific air pollution. He notes:

One of the biggest changes in urban governance in this century has been mayors’ recognition that promoting private investment requires protecting public health—and protecting public health requires fighting climate change.

I have personally found that, even in “red” states in the U.S., it is easy to find public officials in the larger cities who recognize this problem and are attuned to the exigencies of climate change. Mayors have far less latitude for climbing on a soap box with opinions rooted in ideology because they must daily account for the welfare of citizens in very practical matters, such as public health and what draws investors and entrepreneurs to their cities in the first place. Hot air, they quickly discover, won’t do the trick.

Staten Island neighborhood, post-Sandy, January 2013

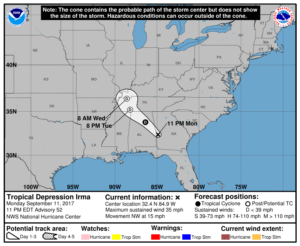

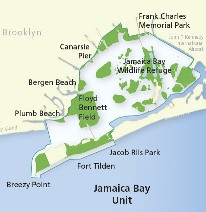

Necessarily, the authors, toward the end of the book, come to terms with the potential consequences of failing to act. Bloomberg, in a chapter titled “New Normals,” describes the state of affairs in New York City after Hurricane Sandy, a storm that could easily have been far more destructive than it already was. For a dozen years, he was the mayor of a city with 520 miles of coastline. To its credit, New York City pursued numerous practical solutions and recognized that no one size fits all, that making the city more resilient would require implementing hundreds of individual steps that dealt with various aspects of the problem. Some of the solutions may seem insignificant, such as restoring oyster beds, but collectively they produce real change over time. Other changes can be more noticeable, such as redesigns of subway systems, changing building codes and flood maps, and rebuilding natural dune systems. The battle against climate change will be won in thousands of ways with thousands of innovations, involving all levels of government, but also businesses, investors, and civic and religious leaders.

All of that leads to the final chapter, “The Way Forward,” which seems to make precisely that point by identifying roles for nearly everyone. Bring your diverse talents to the challenge: the solutions are municipal, political, and financial, and require urban planning, public policy, and investment tools. In the end, although I recognize the potential for readers to quibble with specific details of the prescriptions that Bloomberg and Pope offer, I would still argue that they provide invaluable insights into the practical equations behind a wide range of decisions that our nation and the world face in coming years. The important thing is to choose your favorite practical solution and get busy.

Jim Schwab