Some readers may have noticed that it has been seven weeks since I last posted to this blog (May 13). That delay was not by design but resulted from circumstances. For two weeks immediately after that last item, I was largely on the road, but that has happened before without slowing my pace. What followed most certainly did.

In early April, after sensing some eye strain in late winter, I responded to notices from Pearle Vision that it had been more than two years since my last eye exam. My last prescription for glasses was in 2016. I figured an updated prescription would cure the problem, as it had before.

This time, the optometrist noted some indications of cataracts, though he stated that an ophthalmologist would have to determine whether they were serious enough to require surgery. I took note and arranged for such an exam. There was a little discussion of floaters, and I indicated they had not been a problem. He ordered new lenses, and by late that week, they were installed in my existing frames. I thought I was good to go.

I was dead wrong. Before the weekend was out, I returned to complain that the new lenses had done nothing to cure some blurring, which I attributed to a long-standing combination of astigmatism with my well-defined myopia. I had been near-sighted since childhood and had glasses since I was ten. I am now 69. Glasses have been part of my existence for six decades. The optometrist conceded that he had not tested for astigmatism, noting, to my surprise, that the 2016 exam had shown no sign of it. Astigmatism, which causes blurred vision, can wax and wane over one’s lifetime. In mine, apparently, it had become much less pronounced than I had realized. But he conducted a free second exam and made minor adjustments to the prescription to solve the problem.

By then, there were only two days before I left for San Francisco for the annual National Planning Conference of the American Planning Association. I had to leave with the existing lenses and wait for the new ones to arrive. Pearle called while I was still in California to say that they had arrived, and I visited their store the very evening I returned. I tried on the new lenses. There was still no benefit in clarifying my vision. I decided to be patient and see what would happen—but nothing. I began to realize other factors might be at work.

In scheduling the ophthalmology exam, I contacted the highly regarded clinic at Northwestern Medical Center, part of the Northwestern University hospital system. They first offered an appointment for May 14 because they were booked for a few weeks, but I was already in their system because of a different issue a year before. I had to decline; I would be flying to Winnipeg that day to speak at the Manitoba Planning Conference. The following week, I would be in Cleveland for the annual conference of the Association of State Floodplain Managers. We finally settled on May 30. My own schedule produced the delays.

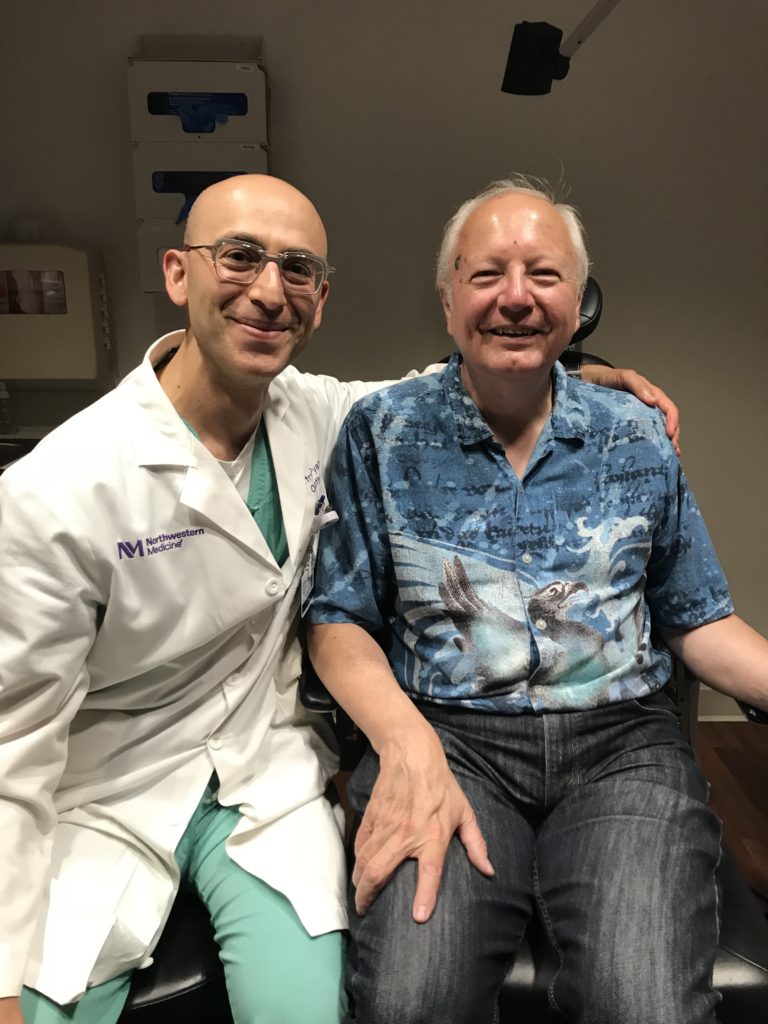

At that appointment, I met Dr. Dmitry Pyatetsky, who conducted the exam. He quickly informed me that my right eye had a serious cataract that needed surgery. The left eye had a smaller cataract, and the wise approach would be to follow with surgery on the second eye. Cataract surgery basically involves breaking up the cataract, which clouds one’s vision, and then replacing the natural lens in the eye with an artificial lens that provides 20/20 vision. I would no longer need glasses, except for reading and computer work. For the first time in my adult life, I would spend most of my day seeing clearly without glasses. Moreover, Dr. Pyatetsky chose to waste no time. Surgery on the right eye was scheduled for June 20, just three weeks later, preceded by some preparatory appointments including a biometric exam to acquire precise eye measurements. That exam also determined that there was nowhere near enough astigmatism to justify Toric lenses, which can correct astigmatism but involve an out-of-pocket expense in the low four figures. I would have spent the money if there had been a problem to solve that insurance would not cover, but I was relieved to find out otherwise.

In fact, I was relieved by many things I learned about modern eye surgery. We live in an age that has made routine many procedures that used to be either problematic or downright dangerous for past generations. I was aware of this already on an intellectual level, but this experience made it personal.

Just a year ago, as an adult nonfiction book awards judge for the Society of Midland Authors, I had read The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine, a remarkable piece of medical history by Lindsey Fitzharris, for which our Honorable Mention was merely one of several prizes, topped by the 2018 PEN/E.O. Wilson Prize for Literary Science Writing. This graphic, often gruesome story made me acutely aware of the benefits we enjoy from medical advances, for only two centuries ago, it was demonstrably dangerous to visit doctors or hospitals, who understood nothing about germs and infections and seldom bothered to clean the instruments with which they performed their surgeries. The result was a high death rate but no grasp of their cause. The story details Dr. Joseph Lister’s struggle to prove that sanitation was essential, in the face of a medical profession in the Victorian era that preferred not to believe that its own practices put patients at risk. One can, of course, read much more about this monumental shift in medical thinking that put many benighted practices behind us. Nearly 15 years ago, in reading Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield, by Kenneth D. Ackerman, I learned that Garfield’s death in 1881 was more the result of medical malpractice and the refusal of his doctor to accept modern bacterial science than a direct result of the assassin’s bullet. Historically speaking, we are not so far removed from the Dark Ages, yet the medical advances of recent decades have been stunning.

As someone who will turn 70 late this year, I am experiencing a growing appreciation of all that is possible with modern medical practice. Old age no longer need be the cavalcade of horrors that it once was. What is true generally is certainly true of modern ophthalmology. The time is not long past when cataracts were simply a fact of advancing age. The Bible is replete with references to lost vision as a result of age, such as “Isaac was old, and his eyes were dim, so that he could not see” (Genesis 27:1). The situation was common well into the 20th century. Although medical history documents surgical procedures for cataracts dating back for many centuries, a close reading of the techniques mostly reveals what must seem a catalogue of horrors from the perspective of modern patients. Couching, in which the lens was pushed into the rear of the eye with a curved needle, was replaced in the 1700s, at least in Europe, by extraction, which broke up the cataract and sucked it out. Johann Sebastian Bach underwent couching but remained blind and, in his case, died four months later. Nothing about these procedures sounds pleasant or painless, or without profound side effects.

It was not until the 1940s that British ophthalmologist Harold Ridley hit upon the use of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), a type of plastic that lacks any inflammatory qualities (so long as it does not touch the iris) as an artificial lens implant, now known as the intraocular lens (IOL). Among the inspirations for this approach to restoring sight was the observation that Royal Air Force pilots in World War II showed no adverse impacts from absorbing PMMA when their fighter plane shields were shot out by German planes, leaving tiny shreds of PMMA shrapnel in their eyeballs. This biological tolerance for PMMA paved the way for the first transplant of an IOL in 1949 in London. Subsequent innovation introduced the use of phacoemulsification, which permits the use of ultrasound to emulsify the natural lens and eliminate the need for removal with an incision. In short, the past half century of medical improvements in this field has made a world of difference for patients like me in 2019. The surgical success rate is now somewhere around 99.5 percent. Especially considering that I had almost no other health problems that might interfere with recovery, I was happy to take those odds. In fact, by the time the second surgery was conducted, on the left eye, on June 26, I was mostly just anxious to get it all over with.

The reason was simple. Until April, I was not even aware I had a cataract and had never given the possibility of it much thought. However, by May, aware that new glasses had solved nothing but increasingly aware of my own blurred sight, I found myself increasingly limited in my ability to read or work efficiently. One turning point came while I was in Manitoba. My agreement with the Manitoba Planning Conference was both to lead a three-hour workshop on the opening day (Wednesday) and provide a keynote address on the closing day. The workshop posed little challenge because I had converted a lengthy article I had produced for the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science, on “Planning Systems for Natural Hazard Risk Reduction,” into a teaching format with substantial audience participation. It was a small group in a small room, I knew the material thoroughly, and my need to rely on the screen to see my PowerPoints was minimal. Nothing challenged my visual acuity. Then, on Thursday, I was introduced to the format in the ballroom for the next morning’s keynote, in front of 250 Canadian planners. Two large screens would be on either side of me, facing the audience, but speakers should face the audience and not be looking at those screens, so another, smaller screen was set at the base of the dais, away from audience view, but allowing me to see the slide on display.

I quickly realized there was one problem: I could not see the slides clearly. I knew right then that I did not want to be squinting at slides in the middle of a tightly timed, 45-minute presentation. I simply had to know the slides intimately so that the broad image reminded me of what I wanted to say even if I could not quickly or clearly discern the details of a graph.

And so it was. I undertook the extra work of memorizing those details overnight because only rarely do I speak from a script. I prefer to be able to remember what I want to say about each slide, but under ordinary circumstances, I can also see that slide in front of me, on a laptop screen or, in this case, a screen sitting on the platform. In this case, I had to wing it. I did it, and all was well. The main lesson was that I realized I had a noticeable problem two weeks before the ophthalmological exam confirmed it. For some people, cataracts grow slowly and can remain small enough not to merit surgical attention for months or even years. In my case, the cataract grew quickly, and my life had to adjust accordingly.

All that said, the adjustment has changed a significant aspect of my life permanently. I have reading glasses for computer work and reading newspapers, books, and the like. But for all other purposes, including driving and physical activities, I now benefit from 20/20 vision. I am grateful to the medical staff at Northwestern, including Dr. Pyatetsky, for their outstanding care and patient services. They have been excellent. I am also simply grateful for living in the 21st century. There was a time when people like me had few options once they had grown old “and their eyes grew dim.”

Instead, I can enjoy life, exercise safely, and continue to contribute to the world and community around me. I consider that the very essence of satisfaction with life.

Jim Schwab