About six weeks ago, as the Biden administration was first asserting its priorities regarding climate change and the environment, I reviewed a book about the positive actions already being taken by cities around the world in addressing the climate crisis. The important takeaway was that, while climate policy languished or moved backwards under the Trump administration, cities and their mayors had not waited for national governments to act. They had instead taken the initiative.

But city governments are not alone. Architects, planners, engineers, and even developers have innovated in their own ways. In late 2019, Chicago architect Douglas Farr provided me with a copy of his book, Sustainable Nation: Urban Design Patterns for the Future, and I promised to review it. It is a sizeable, oversize, 400-page tome, but don’t let that intimidate you, even if I got sidetracked for numerous reasons and only a year later decided to devour the book from cover to cover. That is not necessary for everyone. The book functions much like an encyclopedia, reference work, or anthology. Farr solicited specialized contributions from numerous practitioners and experts. Pick a chapter, pick your favorite subtopic, or dive in randomly. You won’t fail to learn something, as I did, despite my general familiarity with Farr’s subject matter.

My timing in finally reviewing the book has proven fortuitous, in a way. It allows me to expand the message of the review of David Miller’s Solved, a much shorter book by a single author. Miller essentially is a success storyteller; Farr is a documenter. Both serve a purpose.

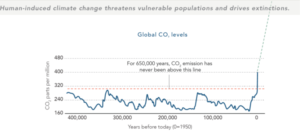

For 650,000 years, global carbon dioxide emissions have never been above the read line. They are now. All graphics courtesy of Farr Associates

Farr starts his book with a “Where We Are” section that includes color-coded maps documenting the huge disparities around the world in longevity (50-59 years in much of Africa, 70-79 in the U.S., above 80 in Japan, Australia, Canada, and Europe, in poverty, gender inequality, and so forth. A simple chart of global CO2 levels demonstrates that, within our lifetimes, we have nearly doubled atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations to levels not seen in the last 650,000 years. A parade of such graphics makes clear that ours is a planet on a collision course with natural reality.

But such searing images also clarify the importance of examples of what can be done. Farr leads us to the specific example in Seattle of the Bullitt Center, which he terms the “most sustainable office building in the world.” Composting toilets use an average of two tablespoons of water per use. There are no parking spaces, but there is 243 square meters of rooftop green space. The Bullitt Center earned designation as one of the first eight buildings to achieve full certification under the Living Building Challenge, and the first office building.

But no one in Seattle wants it to retain such titles. They would rather see new buildings and new developments claim new titles and surpass the Bullitt Center’s achievements as we move toward an entire new sustainable society. Farr takes us from “our default world” to “our preferred future,” with a procession of examples of how this can be done, then leads readers to a theory of change that discusses how we make change happen, over what timelines, and how we can step on the gas with “acceleration strategies” to make practical impacts on climate change happen more quickly.

But it is in the final section, “The Practice of Change,” which dominates more than half the book, where Farr enlists a variety of expert contributors to share the methods and designs that will carry us forward to reduce climate impacts and ultimately create a more livable society. This is not just about innovative building design but about human relationships. Mary Nelson, president and CEO emeritus of Chicago’s Bethel New Life Inc., and one of the pioneers of Chicago neighborhood change whom I most admire, discusses how we build strong relationships between people and place (spoiler alert: it involves hard work). Others describe the value of participatory art in communities or the need to transform public spaces into welcoming places (Fred Kent, president, Project for Public Spaces). Get the point? Architectural or planning solutions that have no human connection of involvement beyond an elite are dead letters in promoting real social change that will have any impact on our climate crisis. It’s all about us, whether the subject is local food culture, local planning checkups, ore re-envisioning underutilized space to promote equitable prosperity. Every single example has its champion in this book, someone who has worked on solutions and involved people in finding answers.

For a moment, I’d like to focus on contributions by two colleagues with whom I have worked, David Fields and Tom Price, to make the point. Fields is a veteran transportation planner now working in Houston as the city’s chief transportation planner, who discusses how elements of the urban setting such as residential density and mixed land uses that put homes within walking distance of retail, or put homes above ground-floor retail, can reduce vehicle trips by up to 90 percent, thus helping to reverse the tremendous negative impact of the automobile on the world’s climate, to say nothing of air quality. Price, on the other hand, is a civil engineer, instructs us on how to use “every project as an opportunity to process rainwater and stormwater,” while demanding beauty through improved design. His articles remind me of a lesson I learned years ago, after Hurricane Katrina, through a project in New Orleans called the Dutch Dialogues, in which the American Planning Association and others engaged with Dutch planners and engineers to promulgate the idea of seeing water not as the enemy but as a resource for enhancing urban quality of life. We need to find ways to help move water elegantly through the city instead of constantly finding ways to bury it, hide it, or divert it.

Whether the subject is community theater, transportation, or architectural styles that build housing affordability and reduced heating and cooling demands to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the overall point is not only repetitive but cumulative: For many of the challenges that climate change poses to our communities, we already know the answers if we are willing to explore the most innovative, effective, and creative approaches that others have already used. Yes, we have a new administration willing to rejoin the Paris climate accord and invest in solutions to climate change. That is important, as we need to push envelopes constantly and with urgency. But we dare not ignore the answers that are all around us in the innovations that are already helping our communities adapt to a carbon-neutral, democratic, more equitable future. They embody the lessons that, through replication, will accelerate our shift to a green future that eases the existential climate crisis of our planet.

Perhaps two points in Farr’s book, side by side, will help illuminate the point. One is a segment by Jason F. McLennan, founder of the Living Building Challenge. He defines something he calls the “sweet spot” in the sustainable urban fabric, buildings between four and eight stories high. These are buildings not so high as to isolate people on upper floors from fellow human beings at ground level. The building is also not so tall that reliance on energy-consuming elevators drives high energy demand for the building merely to function. There is a place for taller buildings, but the combination of density and manageable energy demand with the potential to minimize demands on the environment exists in that “sweet spot.” Subsequent examples in the same section

proceed to elaborate on ways we already know to produce affordable, carbon-neutral housing. At the end of the book, in contrast, Farr makes his plea, in large part to fellow architects, to “end the race to build the world’s tallest building,” detailing the negative effects of such edifices on public health, safety, and welfare, and ending with a quote from Sherrilyn Kenyon, “Just because you can doesn’t mean you should.” Indeed. That is the fundamental point of stranded carbon, that is, leaving fossil fuels unburned, in the ground, and shifting to a renewable energy economy.

Much of the secret of achieving this goal lies in knowing when to stop doing the wrong things and how to enable our society to do more of the green things. This being merely a blog post, I cannot attempt to share all the specific points Farr and his contributors make concerning street design, building envelopes, solar power, social equity, and commitment to environmental health. But I can urge you to seek out his book, in a library, online, or in a bookstore, to find the examples you need for the situation your own community faces in crafting a more sustainable future. This is the activist’s and practitioner’s manual to help get you started. Let’s all engage in some creative thinking and problem solving.

Jim Schwab