There is something mildly disconcerting about visiting an intriguing city several times without having the spare time to go tourist. I first visited Charleston, South Carolina, in 2003, for a business meeting with the National Fire Protection Association, for which I led an American Planning Association consulting project evaluating the impact of NFPA’s Firewise training program. I wandered a few blocks from the hotel but got only a cursory impression of what the city had to offer. In more recent years, I have been there repeatedly for various meetings and conferences connected to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coastal Services Center. This led to considerable familiarity with some of the local hotels and restaurants but still did not afford many opportunities to simply wander.

There is something mildly disconcerting about visiting an intriguing city several times without having the spare time to go tourist. I first visited Charleston, South Carolina, in 2003, for a business meeting with the National Fire Protection Association, for which I led an American Planning Association consulting project evaluating the impact of NFPA’s Firewise training program. I wandered a few blocks from the hotel but got only a cursory impression of what the city had to offer. In more recent years, I have been there repeatedly for various meetings and conferences connected to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coastal Services Center. This led to considerable familiarity with some of the local hotels and restaurants but still did not afford many opportunities to simply wander.

This year, I decided to fix that problem. My wife, Jean, had never been there. We chose our 30th anniversary (June 8) as an excuse for a four-day visit. Besides, it was time for a vacation. Proposals, projects, meetings, and budgets could all wait.

Even as a vacation, it was a view of Charleston through the eyes of an urban planner. None of us leave our experience, knowledge, or even our biases behind. Mine lean toward intellectual inquiry and a fascination with history. Charleston is chock full of history and geographic challenges, which make for interesting environmental history. The old city sits on a once marshy peninsula facing the Atlantic Ocean with the Cooper River to one side, and the Ashley River to the other. Plantations and a thriving rice culture were once built on those foundations. The rice culture, however lucrative it may have been, was built on one other foundation that vanished after the Civil War: slavery. With its demise, and the rise by the late 19th Century of agricultural machinery for rice growing in Texas and Arkansas, rice died as a central feature of the South Carolina economy.

The story is told vividly in the South Carolina Lowlands exhibit in the Charleston Museum, a two-story building on Meeting Street along what is known as the Museum Mile. As that sobriquet suggests, the city has a great deal to offer in this respect, most of which we did not have the time to visit. The offerings include a Children’s Museum of the Lowcountry, the Confederate Museum, and the Gibbes Museum of Art, currently being renovated, among several others. The Charleston Area Regional Transit Authority makes these attractions readily accessible to visitors with three free trolley lines that come together on John St. in front of the Visitor Center, which sits between King St., largely a commercial corridor, and Meeting St. Of the three, the Green Line (#211) runs the length of the Museum Mile.

The story is told vividly in the South Carolina Lowlands exhibit in the Charleston Museum, a two-story building on Meeting Street along what is known as the Museum Mile. As that sobriquet suggests, the city has a great deal to offer in this respect, most of which we did not have the time to visit. The offerings include a Children’s Museum of the Lowcountry, the Confederate Museum, and the Gibbes Museum of Art, currently being renovated, among several others. The Charleston Area Regional Transit Authority makes these attractions readily accessible to visitors with three free trolley lines that come together on John St. in front of the Visitor Center, which sits between King St., largely a commercial corridor, and Meeting St. Of the three, the Green Line (#211) runs the length of the Museum Mile.

From our perspective, the history of the South Carolina Lowcountry makes up the best piece of the exhibits the Charleston Museum offers, and clearly the most extensive, using a combination of glassed display cases and short videos to tell the story from prehistoric Indian tribes to European settlement and Indian displacement, to colonization, the American Revolution and Civil War, to modern Charleston. Another exhibit, for those more biologically inclined, details the flora and fauna of the region, and two other, smaller exhibits display both the clothing of the area over time, and the furnishings and metalware of the early American presence. It is enough, if one is diligent about it, to occupy the better part of a day. The museum also contains an auditorium for special events.

The Joseph Manigault House, viewed from the Temple Gate.

The museum also owns two old houses that have been preserved and are open to the public. The Joseph Manigault House, named after a French Huguenot descended from religious fugitives to America in the 1600s who became wealthy planters by the early 1800s, was designed by the owner’s brother and completed in 1803 using Adam-style architecture. Among its features is a Gate Temple that was left intact in the mid-20th Century even as an Esso gasoline station operated on the property before the museum finally acquired it well after World War II. During the war, it was used by the USO to entertain service men stationed in Charleston. It is on Meeting St. across a short side street from the Charleston Museum.

The Heyward-Washington House, on the other hand, requires either a long walk down Meeting St. or a ride on the Green Line to the corner of Broad and Church St., at which

Backyard gardens of the Heyward-Washington House.

point one hikes a block south to a home modestly tucked between other buildings in an area that was urban even when the house was built, just before the American Revolution in 1772. It belonged initially to Thomas Heyward Jr., among other things a signer of the Declaration of Independence, but it never belonged to a Washington. President Washington, during a tour of the southern states in 1791, simply stayed there for one week in June as a guest of the Heywards. More interestingly, the home later became the property of John F. Grimke, who with his wife produced two daughters, Sarah and Angelina, who developed profound differences with their rich, slave-owning, planter parents. The daughters became radical abolitionists. Needless to say, they became less than welcome in South Carolina, which posted a warrant for their arrest. That never happened because they resettled in Philadelphia, where they became Quakers, allied themselves with other abolitionists, and continued their activities, speaking and writing widely for their cause. There is no doubt they remained a thorn in the side of their southern kin until the day they died.

But by now I am well ahead of, well, our trip. Neither the Charleston Museum nor the two historic homes were among the first things we saw. In fact, we arrived on Sunday, relaxed over brunch at the eminently affordable yet well-managed Town & Country Inn & Suites in West Ashley, a quieter part of the city west of downtown across the Ashley River, and finally made our way across not only the Ashley but the Cooper River, traversing the magnificently attractive Arthur Ravenel Bridge to Patriots Point in Mount Pleasant. The dock is home to the U.S.S. Yorktown, a World War II aircraft carrier now preserved as a museum for visitors. We did not happen to buy tickets for that while we were there, but it does look impressive from dockside.

But by now I am well ahead of, well, our trip. Neither the Charleston Museum nor the two historic homes were among the first things we saw. In fact, we arrived on Sunday, relaxed over brunch at the eminently affordable yet well-managed Town & Country Inn & Suites in West Ashley, a quieter part of the city west of downtown across the Ashley River, and finally made our way across not only the Ashley but the Cooper River, traversing the magnificently attractive Arthur Ravenel Bridge to Patriots Point in Mount Pleasant. The dock is home to the U.S.S. Yorktown, a World War II aircraft carrier now preserved as a museum for visitors. We did not happen to buy tickets for that while we were there, but it does look impressive from dockside.

We did have tickets for a dinner cruise that evening aboard the Spirit of Carolina, a much smaller vessel designed to provide a pleasant experience for those who like to eat a fine dinner while watching the waves and the birds and the pleasure boats in Charleston Harbor. Both of us enjoyed a well-prepared meal of rib-eye steak, foreshadowed by she-crab soup and a house salad, accompanied by a bottle of champagne provided for our anniversary, and topped off by key lime pie for dessert. To

We did have tickets for a dinner cruise that evening aboard the Spirit of Carolina, a much smaller vessel designed to provide a pleasant experience for those who like to eat a fine dinner while watching the waves and the birds and the pleasure boats in Charleston Harbor. Both of us enjoyed a well-prepared meal of rib-eye steak, foreshadowed by she-crab soup and a house salad, accompanied by a bottle of champagne provided for our anniversary, and topped off by key lime pie for dessert. To  be honest, I do not expect the absolute best of cuisine on dinner cruises; there are some natural limitations built into the format. The cruise is the point of it all. But this was excellent nonetheless. We both came away satisfied. With the help of some gentle guitar music and the breezes that greeted us during our short visit to the upper deck, it was an enjoyable way to celebrate an anniversary. By 9:15 p.m., as our boat pulled ashore to let everyone out, we felt our hosts had treated us to a very pleasant evening.

be honest, I do not expect the absolute best of cuisine on dinner cruises; there are some natural limitations built into the format. The cruise is the point of it all. But this was excellent nonetheless. We both came away satisfied. With the help of some gentle guitar music and the breezes that greeted us during our short visit to the upper deck, it was an enjoyable way to celebrate an anniversary. By 9:15 p.m., as our boat pulled ashore to let everyone out, we felt our hosts had treated us to a very pleasant evening.

The next day our target was the South Carolina Aquarium. Given the geography, and aquatic and maritime history, of Charleston, this aquarium is a natural feature of the city. It is situated on the eastern waterfront of Charleston, a few blocks east of Meeting St., but also accessible by trolley. (It also hosts a parking garage.) One can easily  spend a day there, and we spent most of a day there, absorbing the living exhibits of sea life that give patrons insights into aquatic life of all sizes and the ecological challenges facing much of it today. With such scientific powerhouses as NOAA nearby, one has high expectations of the aquarium for its scientific content, and by and large it delivers. One unusual feature, somewhat removed from its context, is the Madagascar exhibit, including some lemurs in a tree. I do not profess to know how that fits with the rest of the material, but it is edifying nonetheless. One learns of the utterly tiny amount of paved roads on an island nearly the size of Texas with nearly as many people but a declining rainforest. More related to the region, we discovered to our surprise an entire section devoted to piedmont ecology, examining the river life and aquatic ecology of the foothills of the Appalachians. If you can afford the time, the aquarium is well-endowed with such pleasant surprises. We arrived late in the morning but did not leave until about 4 p.m.

spend a day there, and we spent most of a day there, absorbing the living exhibits of sea life that give patrons insights into aquatic life of all sizes and the ecological challenges facing much of it today. With such scientific powerhouses as NOAA nearby, one has high expectations of the aquarium for its scientific content, and by and large it delivers. One unusual feature, somewhat removed from its context, is the Madagascar exhibit, including some lemurs in a tree. I do not profess to know how that fits with the rest of the material, but it is edifying nonetheless. One learns of the utterly tiny amount of paved roads on an island nearly the size of Texas with nearly as many people but a declining rainforest. More related to the region, we discovered to our surprise an entire section devoted to piedmont ecology, examining the river life and aquatic ecology of the foothills of the Appalachians. If you can afford the time, the aquarium is well-endowed with such pleasant surprises. We arrived late in the morning but did not leave until about 4 p.m.

Although we did not find time to undertake the tour to Fort Sumter, we did visit the Fort Sumter National Monument, a modest building next to the aquarium that houses some displays pertinent to the battle that launched the Civil War when Confederate forces shelled the Union fortress on a small island in Charleston Harbor. Tour boats depart from the piers behind the building, and it is probably worth a visit. I hope to accomplish that on a future trip. The Fort Sumter National Monument, unlike the tour, is free and open to the public, and managed by the National Park Service.

Although we did not find time to undertake the tour to Fort Sumter, we did visit the Fort Sumter National Monument, a modest building next to the aquarium that houses some displays pertinent to the battle that launched the Civil War when Confederate forces shelled the Union fortress on a small island in Charleston Harbor. Tour boats depart from the piers behind the building, and it is probably worth a visit. I hope to accomplish that on a future trip. The Fort Sumter National Monument, unlike the tour, is free and open to the public, and managed by the National Park Service.

That evening, we cheated, but who cares? We engaged a second establishment, Stars, in helping us celebrate our anniversary, this time on the actual date. I have previously reviewed Stars on this blog. So why not try something new instead? For starters, Jean had never been there; I had been there with colleagues during business trips. After reading my most recent review, Jean insisted she wanted to try the place herself, so I made a reservation. Upon arrival, after checking in with the maître d’, I took her upstairs to see the rooftop bar, where we were promptly served Bellinis, after a short explanation of a drink new to both of us. We loved it. Back downstairs, we got the royal treatment from a waiter who one of the owners subsequently informed us was “Big John,” as opposed to “Little John,” also working there, who was at that moment at the front of the restaurant. Big John had migrated from up north but, for the moment at least, found Charleston to his liking.

That evening, we cheated, but who cares? We engaged a second establishment, Stars, in helping us celebrate our anniversary, this time on the actual date. I have previously reviewed Stars on this blog. So why not try something new instead? For starters, Jean had never been there; I had been there with colleagues during business trips. After reading my most recent review, Jean insisted she wanted to try the place herself, so I made a reservation. Upon arrival, after checking in with the maître d’, I took her upstairs to see the rooftop bar, where we were promptly served Bellinis, after a short explanation of a drink new to both of us. We loved it. Back downstairs, we got the royal treatment from a waiter who one of the owners subsequently informed us was “Big John,” as opposed to “Little John,” also working there, who was at that moment at the front of the restaurant. Big John had migrated from up north but, for the moment at least, found Charleston to his liking.

This time, we diverged in our orders, Jean getting steak (with black truffle grits and bacon braised mushrooms) while I ordered sea scallops. But neither entrée, while excellent, stole the show, at least in our estimate. That honor was reserved for a special share plate that featured cauliflower and broccolini roasted in a cheddar cheese sauce that was as good and succulent as any appetizer I can remember in a long time.

On Tuesday, our afternoon visit to the Charleston Museum followed a morning visit to the Waterfront Park, much closer to the Battery at the end of the peninsula than to the aquarium and most of Museum Mile, but still accessible by trolley. The park is simply a wonderful outdoor setting in which to view the ocean, complete with fountains, palm trees, and walkways along the water’s edge. It is a very pleasant place to pass some time, especially on a warm summer day. It looks like a wonderful venue for an outdoor wedding and has been used that way. For those who simply want to use their laptop or mobile device while occupying one of many park benches, it is also fully equipped with wifi, courtesy of Google and the Charleston Digital Corridor.

On Tuesday, our afternoon visit to the Charleston Museum followed a morning visit to the Waterfront Park, much closer to the Battery at the end of the peninsula than to the aquarium and most of Museum Mile, but still accessible by trolley. The park is simply a wonderful outdoor setting in which to view the ocean, complete with fountains, palm trees, and walkways along the water’s edge. It is a very pleasant place to pass some time, especially on a warm summer day. It looks like a wonderful venue for an outdoor wedding and has been used that way. For those who simply want to use their laptop or mobile device while occupying one of many park benches, it is also fully equipped with wifi, courtesy of Google and the Charleston Digital Corridor.

Hiking up the street past the old Custom House and turning left at Market St., we reached the popular City Market, a stretch of airy long buildings containing booths featuring numerous local artists and jewelry makers, among others. From one of them I eventually bought a small matte painting of a tropical seashore for my office. It will serve me well on cold Chicago winter days. We also ate lunch at an open air restaurant nearby, the Noisy Oyster, which offered commendable seafood at very reasonable prices. (By this time we were looking to limit both our food expenditures and our caloric intake.) From City Market we took the trolley back to the Visitors Center, where we had parked in the garage for the day, but first took our detour into the Charleston Museum, across the street.

After leaving the museum to get our car, however, we noticed the ominous, heavy gray clouds gathering overhead. Something told us the better part of wisdom lay in returning to our hotel, where we could read our books. (I was working on the H.W. Brands biography of Ben Franklin, The First American. I like to tackle the 700-page heavyweights during vacations.) By the time we arrived at the hotel, the rain was beginning to drip but not coming down very fast. Soon enough, however, the lightning and thunder mounted, and the rain pounded. On the television, we saw news reports from King St. showing cars struggling through several inches of water. I soon learned that much of downtown is either below sea level or at very low elevations with poor drainage, making for a chronic problem of urban flooding. Charleston, also subject to tropical storms such as Hurricane Hugo, which devastated the area in 1989, was not quite the seaside paradise we had enjoyed until then. It is, in fact, one very vulnerable coastal city that also experiences occasional tremors from a fault that triggered a major earthquake in 1886. Charleston needs good disaster plans.

Charleston needs a few other things as well. On our final day, after visiting the Heyward house, we took a long stroll up King St. back in the direction of Stars and the Visitors Center. On a hot day, that can be challenging, so we tried our best to hew to the shady side of the street, though at noon in June, there is a period when no such thing exists. What does exist is a wide variety of old and new storefronts, and we ended up buying some flip-flops and shoes in an H&M store, lunch at the 208 Kitchen, a pleasant little lunch establishment with good sandwiches at single-digit prices, and delicious Belgian gelato at a small store called, well, Belgian Gelato. Eventually, Jean, having finished off her murder mystery, wanted something new to read and found out there was a Barnes & Noble bookstore around the corner from the Francis Marion Hotel, a charming historic place where I have stayed on several previous trips to Charleston. She decided to try Identical by Scott Turow, a Chicago-area writer and fellow member with me of the Society of Midland Authors.

So what does Charleston need? As helpful as the trolley is, and although there is bus service provided by CARTA, it is clear that the creaking, older part of the city is ultimately facing a challenge of mobility as a result of too much dependence on the automobile. Light rail would help, and some people told me it had been discussed, but the big question is how to retrofit it into the existing fabric of this historic core of the city.

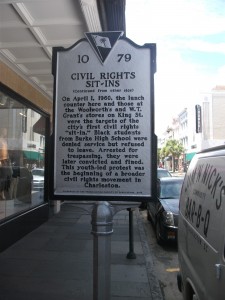

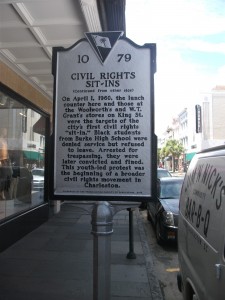

With all the tourism the city is now attracting, it is also facing the classic challenge of most such aging urban magnets of maintaining affordable housing for the workforce it needs to support such attractions within a reasonable distance of their employment. Already there is an obvious outmigration of the working poor to areas like North Charleston, a suburb that has very recently experienced toxic racial tensions between citizens and police, particularly after the shooting of Walter Scott this spring. When we researched hotel prices in preparation for our trip, it became obvious that the downtown area is experiencing significant price escalations. Charleston can easily allow the old city core to become a playground for the affluent, a tax generator as such, but it cannot afford to lose its character in the process. Charleston has come a long way since the lunch counter sit-ins of 1960 and the segregationist politics of Strom Thurmond. The challenge now is to preserve its well-earned reputation by honoring that progress in a progressive fashion. A cursory reading over breakfast of local newspapers told me that issue is far from settled in the development debates that are currently underway.

With all the tourism the city is now attracting, it is also facing the classic challenge of most such aging urban magnets of maintaining affordable housing for the workforce it needs to support such attractions within a reasonable distance of their employment. Already there is an obvious outmigration of the working poor to areas like North Charleston, a suburb that has very recently experienced toxic racial tensions between citizens and police, particularly after the shooting of Walter Scott this spring. When we researched hotel prices in preparation for our trip, it became obvious that the downtown area is experiencing significant price escalations. Charleston can easily allow the old city core to become a playground for the affluent, a tax generator as such, but it cannot afford to lose its character in the process. Charleston has come a long way since the lunch counter sit-ins of 1960 and the segregationist politics of Strom Thurmond. The challenge now is to preserve its well-earned reputation by honoring that progress in a progressive fashion. A cursory reading over breakfast of local newspapers told me that issue is far from settled in the development debates that are currently underway.

Jim Schwab