I know. My very title for this blog post sounds to some like yet another naïve stab at kumbaya. Well, stay with me, anyway. We are talking about solving problems in our communities, and the more people who get behind the solution, the more successful it is likely to be.

What I am really aiming to write about, in the narrowest sense, is a morning keynote presentation by Kristin Baja at the tenth annual Growing Sustainable Communities conference in Dubuque, Iowa, on October 4. The City of Dubuque has been hosting this event from the outset, and I rather like the riverside convention center where they host it. Hell, I rather like the mystique of the Mississippi River, the very reason Dubuque exists. I’m fascinated enough that I thought the conference a good venue for meeting people who might be useful to my pet project since leaving the American Planning Association (APA) at the end of May: a two-book series on the 1993 and 2008 Midwest floods. Dubuque is one of those communities that understands that environmentally healthy communities are a necessary path to the future.

That is why they engaged Kristin Baja, a former planner for the city of Baltimore who was instrumental in effecting significant changes in planning that recognized the fundamental problems that Baltimore needed to address, both socially and environmentally. She openly states that Baltimore was built on a legacy of racism that must be overcome through new approaches that must complement the city’s efforts to address climate change. The poor tend to be more vulnerable to natural hazards. Recently, Baja left her city position to become the Climate Resilience Officer for the Urban Sustainability Directors Network. In this new role, she is essentially bringing what she learned at the local level to the national stage.

What she seems to have learned most, and emphasized in her keynote, is the value of empathy, a quality often sorely lacking in national politics. I frankly think we are more likely to relearn its value at the community level, where we can engage directly and personally with our neighbors. Perhaps then we can reapply it to national policy discussions if we can get past the angry tweets and the noise of shouting talk show hosts.

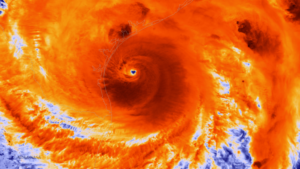

Baja started with a display of many of the same points I have made in this blog before. The climate is changing, and we have plenty of evidence to make this point if we can get people to listen. We cannot afford to continue to confuse weather with climate, for instance, by using one snowstorm to ridicule the entire notion of global warming. “Weather is your mood, climate is your personality,” she suggested, and it is not a bad analogy for helping people to grasp the distinction between short-term and long-term trends. If we are to achieve resilience in our communities, it will be essential to understand that we must build community strength in the face of both shocks, which are sudden and unexpected changes, and stressors, those long-time problems that weaken a community’s social fabric, like high unemployment, poverty, racism, and distrust of authority. If community leaders want to overcome some of that malaise, it is critical that they foster and sustain mutual trust, be accountable, keep promises, share power, value people’s time, and focus on community cohesion. It may be a tall order, but I would add one other factor. When a community finds such leaders, it needs to honor them. Too often, the best intentions are drowned in a tidal wave of vitriol.

I will not reprise every aspect of Baja’s captivating presentation. What I want to share is the underlying logic of her approach. She first came to my attention when I learned about Baltimore’s now well-known DP3 project, which stands for Disaster Preparedness and Planning Project. DP3 resulted in the approval in 2013 of a combined local hazard mitigation plan and climate adaptation plan. Baja participated in a July 2016 webinar I organized for APA on the subject of merging climate adaptation and hazard mitigation plans.

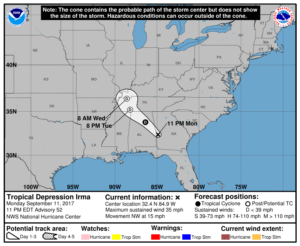

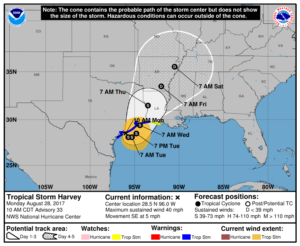

Hazard mitigation plans have been produced by the thousands by state and local governments ever since the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 decreed that they would be ineligible for federal mitigation grants, which pay for many hazard mitigation projects after disasters, unless they adopted a FEMA-approved plan. All states now have such plans, and about 20,000 units of local government have adopted them, often participating in multijurisdictional efforts. But almost universally, until a few creative cities like Baltimore began to outline a new approach, these plans have been backward-looking in identifying local hazards. Why? Because the standard approach is to project future hazards based on historical patterns. The problem is that climate change is disrupting those expectations and exacerbating existing vulnerabilities. The path to resilience lies in using climate science data to anticipate the hazards of the future. Baltimore accomplished that by integrating data about climate trends into its hazard mitigation plan, thus elegantly addressing both existing and future hazards. Baja was at the center of this activity.

But her innovative style goes farther. She worked on the use of vacant lots in cities for development of green infrastructure to help remedy urban flooding. In March of this year, she attended the first of two day-long roundtables APA organized with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on ways to integrate climate science into the local planning process. She was feisty and persuasive as usual, and we all appreciated her contributions.

Ultimately, what Baja discussed with the audience was not merely the policy changes that are needed to produce climate-resilient communities, but the practices of community engagement that would undergird those policies and make them stick, embed them in municipal and regional civic culture. She unleashed her own flood of ideas about how to do this, including training staff, as she has done recently in Dubuque, with training games that make the undertaking fun, such as a “Game of Floods.” The laundry list that rolled from her tongue and flowed from the PowerPoint screen included these tips for engaging members of the community and removing barriers to participation in civic meetings:

- Go to people

- Partner with community leaders

- Provide transportation

- Provide food and beverages

- Provide childcare or activities with children

- Consider language barriers

- Translate signs and data

- Insure compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act

- Collect stories

- Approach all stakeholders with empathy

- Provide interactive and fun ways of engagement

- Invite participation on advisory committees

One of her approaches, used in Baltimore to give life to these ideas, was to create a community ambassador network to empower the very people who often labor to advance these ideas through small neighborhood organizations with no financial support from the city. Recognizing the contribution these people make to their city goes a long way to strengthening the trust that supports progressive policy making.

There is a method to the madness of making this all work. Baja is not the only person who has discovered the value of empowering volunteers for good planning, but she herself is now a full-time ambassador through USDN. I’d say they found the right person.

Jim Schwab