For the people of the Texas Gulf Coast, the rain and winds of Hurricane Harvey are just the beginning of a long journey. The storm will last a few days. The recovery will last years.

I am not there, so I can only surmise, based on the news coverage I have seen, the full extent of the damage and suffering that people are enduring in Corpus Christi, Houston, Galveston, and hundreds of other communities in a wide arc that has fallen under the impact of this storm. I do not even expect that people there will read this, certainly not right now. Nonetheless, it may be worthwhile to offer some insights to people elsewhere. I have never lived or worked in Texas, but I have been there numerous times and visited Louisiana more often than I can remember. I saw first-hand the devastation wrought in the Bolivar Peninsula and Galveston after Hurricane Ike. I have worked with people in Texas, including those at the Texas A&M Hazards Reduction and Recovery Center, over many years. They have educated me greatly on the vulnerabilities of their state.

With all due humility, therefore, but also with experience from other disasters over the past quarter-century, I offer some observations that may enhance what readers of this blog may learn from the news.

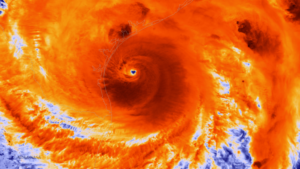

Photo from NOAA. The NOAA/NASA Suomi NPP satellite captured this infrared image of Hurricane Harvey just prior to making landfall along the Texas coast on August 25, 2017 at 18:55 UTC. NOAA’s National Hurricane Center has clocked Harvey’s maximum sustained winds at 110 miles per hour with higher gusts. Infrared images like this one can help meteorologists identify the areas of the greatest intensity within large storm systems, such as the areas with the most intense convection, known as overshooting cloud tops (dark orange), surrounding the eye and along the outer bands. https://www.nnvl.noaa.gov/MediaDetail2.php?MediaID=2086&MediaTypeID=1

First, this is apparently a somewhat unusual storm system. It approached the coast just northeast of Corpus Christi as a Category 4 hurricane, although it is now downgraded to a tropical storm. That does not make it less dangerous. The Saffir-Simpson scale that is used to rate hurricane strength deals only with wind speeds. Winds are certainly important, especially when they reach the 130 mile-per-hour range that was the peak for this event. Winds have, from all the visual evidence on the various news outlets I have watched, wreaked tremendous havoc along the coast, tearing apart buildings and overturning trailers and other vehicles. Moreover, hurricanes often spawn tornadoes, and some of the intermittent damage—that is, buildings ripped apart near others largely intact—suggests that this has occurred. In other words, if the more diffuse hurricane winds don’t get you, the tornado just might. It is no laughing matter. It is a wonder the death toll remains relatively low, although we almost surely don’t know the full tally just yet.

One specific impact that always accompanies coastal storms of this magnitude is storm surge, the waters pushed landward by the winds that in this case ranged from six to twelve feet. These can do considerable damage in low-lying areas along the coast and may also exacerbate coastal erosion.

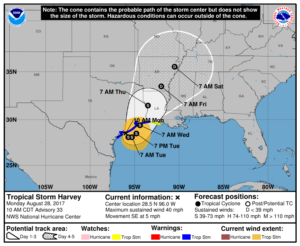

What makes the storm somewhat unusual also makes it dangerous even after being downgraded to a tropical storm. The storm system appears to have stalled a bit on Sunday and may even be backing out into the gulf for another landfall. At least two very serious consequences can flow from this. One is that the stagnant storm front will dump immense amounts of rain over consecutive days. The projected precipitation totals, even larger than what has fallen so far, mount up, so that projections for many communities range as high as 50 inches. Keep in mind that 30 inches is ample rainfall for an entire year in many parts of the country, and almost no city in the United States is prepared to absorb even half that amount in just a few days. The average yearly rainfall in Houston is just shy of 50 inches.

Moreover, as the storm moves back out over the Gulf of Mexico, it may regain strength that storms typically lose as they make landfall. Tropical storms draw their strength from the warmth of the water over which they pass until they make landfall, after which wind speeds begin to die down. The water of the Gulf right now is in the mid- to high 80s Fahrenheit, reportedly a full two to three degrees above average. That is the source of the strength of Harvey. Regaining any strength from the warm Gulf waters is not a good omen for the Texas coast, and as the storm moves slowly northeast, more of this will affect Houston than was originally the case. That is why we are seeing such intense scenes of flooding in Houston: The storm began with enormous amounts of moisture and has moved along the coast at a snail’s pace, at times just a mile an hour. As the week progresses, however, the storm is projected to move northeast over Louisiana and Arkansas, weakening along the way.

Of course, those warm waters raise questions about the influence of global warming, a topic that does not always receive a warm reception in Texas political circles. It is impossible to say that a specific storm like Harvey would not have happened but for climate change. It is also possible to say very credibly that warmer waters make stronger storms possible. Warmer waters can reflect seasonal and yearly variations, but over time they can also reflect climatic trends. For now, let’s leave it at that. People will have plenty of time later to debate this topic. In due course, as recovery proceeds, it should become a topic of reasonable, informed public discourse.

Other factors are at work as well. The sheer extent of flooding reflects the inexorable fact that the ground in any area has limited capacity to absorb rain. The hydrological cycle allows much rain under normal circumstances to drain into the ground, depending on the types of soil present in any given location. Sand absorbs very well but does not provide a very solid building foundation. Clay provides a better foundation but does not absorb water as quickly. Soil types matter, therefore, but in urban areas we have complicated matters greatly with large quantities of impervious surface that absorb little or no water by design. Impervious surface includes buildings (with the limited exception of green roofs), paved surfaces like roads, parking lots, and driveways, and other structural impediments to the movement and absorption of water. Houston is a very large metropolitan area with the fourth-largest population among major cities in the U.S. Although it is making strides, it is also far from the greenest city in America. Like most major cities, the percentage of impervious surface varies widely, depending on density levels in specific neighborhoods and corridors. Flooding is also influenced by the quality of the drainage systems; Houston is challenged in this respect by low-lying, flat terrain. It is criss-crossed with numerous bayous and canals that provide paths for the movement of water but also have serious limits to the water they can absorb before spilling over onto streets and highways. Those water-filled streets are the main obstacle to evacuation for those who stayed behind. There comes a point where people are better off remaining in place than trying to move, which is why Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner chose not to recommend evacuation.

Some dangers of mass evacuation for 6.5 million people are self-evident: clogged highways that are rapidly filling with water, producing death traps for people in stranded vehicles. Pedestrians cannot see steep drop-offs in elevation as they wade through high waters and can trip and drown. In Houston, the bayous may also contain alligators, water moccasins, and other wildlife hazards that are more easily avoided in dry weather. Moreover, the sheer volume of water can produce eddies and swirls that catch people off guard, and not everyone will be strong enough to regain their footing. Finally, flood water is always dirty water, sometimes just plain filthy, posing a potentially serious threat to public health.

All that said, many other major cities suffer from similar problems. I can think of no city that is prepared for the sheer volume of water currently falling along the Texas coast.

The Texas Gulf Coast communities, therefore, will emerge from this storm with a widespread pattern of both wind- and flood-related damage that will vary significantly from one area to the next, but collectively the costs will probably skyrocket into tens of billions of dollars. It is impossible to know the full costs just yet, but this will almost surely rank as one of the most expensive disasters in U.S. history. The recovery will take years of planning and implementation. If done well, it will involve a great deal of reassessment of patterns of development along the Gulf Coast and of the quality and importance of building codes. Social equity considerations will demand a new examination of the location and quality of low-income housing and the adequacy of affordable housing. Development regulations have seldom been politically popular in Texas, a state that still has never empowered counties to enact zoning codes. Some coastal communities may also wish to look more closely at the prospect of undergrounding utility lines to protect them from hurricane winds.

Events can push public attitudes in new directions. Part of that may depend on new lines of thought gaining traction in the discussion of rebuilding after the disaster. That may require some degree of courageous political leadership. Some very significant changes occurred in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina, including consolidation of levee district management, adoption of a statewide building code, and a charter amendment in New Orleans that gave a new master plan more control over development regulations. We should not make perverse assumptions about outcomes, just as we also should not be naïve about the obstacles. But in my time at the helm of the Hazards Planning Center of the American Planning Association, we certainly worked hard to create a thorough blueprint for those willing to advocate better planning in response to major and catastrophic disasters, and I assume APA remains prepared to further that discussion and provide technical assistance where it can.

There will also be plenty of help available from the federal government, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and other agencies. We can only hope that Congress will sidestep much of its partisan bickering to ensure rapid allocation of the necessary resources. And we can hope that those resources and personnel are managed well to advance the recovery process, which is complicated and daunting.

One encouraging factor in the response has been the emergence of both willing volunteers and the effective use of social media to expedite search and rescue operations. The number of boats driven by volunteers rescuing people from rooftops and the interiors of flooded homes reminded me of the so-called Cajun Navy that operated throughout New Orleans in the desperate days that followed Hurricane Katrina. Disasters have a fortunate tendency in most cases to bring out the best in people, but we are also at a point in history where our new technologies facilitate the ability of willing heroes to find the people who most need help. Even the elderly and disabled are largely capable of dialing 911, or tweeting, or posting photos of their situation on Facebook, sharing their location, and pleading for help—and then finding their guardian angel at the front door with a motor boat. That is a huge advance from only a decade ago because it enables the willing volunteers to become effective heroes. If those civic and humanitarian instincts carry over into the slower grind of recovery, perhaps a stronger, more resilient Gulf Coast can yet rise from the mud, the grime, and the shattered buildings we see now.

Jim Schwab