Robert Loerzel, immediate past president of SMA, helps introduce the day’s events. He was preceded by current SMA president Meg Tebo.

Yesterday (May 2), a modest crowd celebrated 100 years of the Society of Midland Authors with speakers, panel discussions, and readings of authors past at the end of Society of Midland Authors Week, as declared by the Chicago City Council. Unfortunately, the event had to compete with the National Football League (NFL) draft ceremonies just a couple of blocks away in Grant Park, a contingency not foreseen when it was originally planned. While the NFL undoubtedly generates a stupendous sum of revenue even in the process of tagging star college players for professional opportunities, I would humbly argue that the literature of those celebrated at the University Center conference facility on State St. has done more to help define Chicago’s image than football ever will. Professional football shouts its presence from the skyboxes of Soldier Field. The novels, poems, and nonfiction narratives of Chicago and Midwestern writers insinuate their way into our consciousness slowly but pervasively and persuasively, like rainwater percolating into soil. Mind you, I do not dislike sports and spent Friday afternoon at a Wrigley Field rooftop party. But my understanding of real life was never altered nearly so much by a football game as by a really good book. And a few of those books were even about major sports figures.

With that in mind, I am going to divide this article into two parts. In the first, I will describe the centennial itself, which was preceded the night before by SMA’s annual book awards banquet at the Cliff Dwellers Club, which has long offered a home for many literary events, especially including those of SMA. In the second, I will describe my own small role in helping kick off the centennial as the first reader of a past author, poet Vachel Lindsay. I deliberately, several months earlier, asked the rest of SMA’s board of directors to “send me to Heaven” by letting me perform Lindsay’s art. They accommodated me, and I was grateful. The effort was part of a segment of the program in which past presidents of the society chose past SMA members and Midwestern authors whose works they would read, at short intervals between the invited speakers.

The Program

Many people save the best for last, but the best may have come first in some ways. That is saying a good deal because the program lasted from 10 a.m. until nearly 5 p.m.

The Gettysburg panel in action: From left, Peck, Burke, and Knorowski.

Carla Knorowski, CEO of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation, in Springfield, Illinois, led the first panel discussion by describing her work as the editor of Gettysburg Replies: The World Responds to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. The foundation asked potential contributors to write essays of 272 words, the precise length of the manuscript of the famous speech that is on display in the Lincoln Library. Their essays could discuss Lincoln, the Civil War, or any other aspect of the speech’s meaning that touched their souls, as long as they matched Lincoln’s brevity. The library further challenged them to submit their work in longhand, though surely many used the word count features of their computers to guarantee the length before committing their prose to cursive writing. But many found the cursive exercise humbling in an era in which such skills have been lost to many in the younger generation. Lincoln had no such advantage except that he chose the length, which established his unique ability to say so much in so few words. Lincoln was, the panelists said, a Midwestern literary genius in his own right. In the end, Knorowski and her team at the foundation had to choose the best 100 of more than 1,000 submitted essays, some of which arrived as poems, most as essays, and which included as authors every living ex-president, one Holocaust survivor, and numerous others whose observations are well worth the price of the book, which was on sale in the back of the hall.

After her opening presentation, Knorowski was followed by two of those essayists, Chicago Alderman Edward Burke, an author in his own right, who spoke later of Chicago’s storied literary history, and Graham A. Peck, associate professor of history at St. Xavier University in Chicago. Burke noted the political machinations of the Republican convention in the Wigwam in Chicago in May 1860 that made it possible to nominate a lesser known regional leader, Lincoln, in the face of strong national support for William Seward of New York. Without those machinations, of course, the nation would never have elected Lincoln nor grown to respect and love this unique political figure. Peck, on the other hand, noted from his essay that “wisdom, restraint, and self-sacrifice were in characteristically short supply” in Lincoln’s time, but that the true reason for celebrating Lincoln’s words are “with us still: the tentative, incomplete, and unrealized human commitment to freedom, which binds us equally profoundly today, and calls out insistently, everywhere, for a new birth in service of human dignity.”

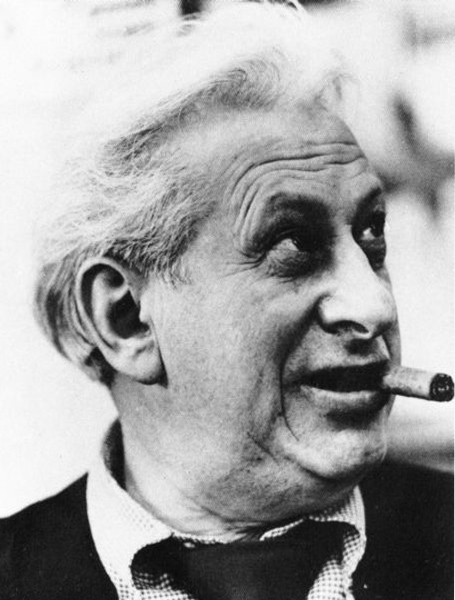

Haki Madhubuti, who was also founder of Third World Press.

Such comments raise the question of exactly how we perceive that commitment in 2015. If a later presentation by 73-year-old poet Haki Madhubuti seemed at times halting, at times even stumbling, there was no doubt he was speaking with conviction and concern about the fate of young African-Americans amid the turmoil of recent events, notably the very recent controversy over the death of Freddie Gray in the custody of the Baltimore police. Asked if he had any hope after his seemingly grim presentation of the state of the black community, Madhubuti stated forthrightly that he saw it in young people of all races who had not been corrupted by the racism of America’s past.

Rounding out the morning was Rick Kogan, journalist and SMA member, who recounted much of the colorful history of Chicago literature and journalism, and said of the future of the written word, “I am hopeful but scared at the same time.”

In addition to the oration of Ald. Burke, the afternoon consisted of three panels involving reporters (Steve Bogira and Jonathan Eig), children’s authors (Blue Balliett and Ilene Cooper), and novelists Christine Sneed, Carol Anshaw, and Rosellen Brown. But surely, due to a conflict that took me to Chuck E. Cheese for a granddaughter’s fifth birthday, I missed the treat of the day. On my way out, I personally excused myself to Dr. Martin Marty, a long-time professor of the history of religion at the University of Chicago, and the prolific author of at least 40 books (but who’s counting?), some of which have won literary awards. I quietly explained my circumstance as he sat in the back of the room, awaiting his turn, and with typical gracious humility as a fellow grandfather, he assured me the birthday was more important. So I asked him later what he had spoken about, and I got this third-person response, which made me laugh hard enough that I have decided to reproduce it in its entirety, with his permission:

Martin Marty, long-time member of the Society and happy possessor of a “lifetime” achievement award, used his twenty-one minutes to introduce readers to a non-existent figure, Franz Bibfeldt. He is available, amply, by the Google route; there are thousands of references to him, and he has many devotees around the world, despite his handicap: he doesn’t exist. Marty explained his light-hearted approach to demonstrate how the world of academic theology does not always take itself too seriously.

Bibfeldt was an invention of Marty in 1951, on the eve of his graduation from theological school and preparation to enter Christian ministry. It was a satire on eccentrics and eccentricities in “the system,” but when the hoax was exposed, not all of the exposed took kindly to it, and they wanted Marty punished. He had been scheduled to his first call to London, and that was canceled. The seminary dean had to follow disciplines, but Marty appealed to the seminary President, a kindly soul who said that instead of London MEM would be assigned to assist a senior minister of note, to be his mentor. It turned out to be Grace Lutheran in River Forest, whose call stipulated that the pastor assistant had to work on a doctorate. That is how, after a couple of years, Marty wound up at the University of Chicago to which, after ten years in pastoral ministry, he returned for a 35-year teaching career. Marty claimed to have made good on his observation that this non-existent person had greater influence on his career than anyone else.

Franz Bibfeldt? Many articles online detail his theology and fame. In a world where too many theologians and other scholars take themselves too seriously, and define things too sharply, Bibfeldt wanted to please everyone. Some would call him “wishy-washy,” but Marty & Co. treat him as someone who agreed with everyone. He knew the famous book by philosopher Soren Kiekegaard; it was called Either/Or. Bibfeldt wrote Both/And, and when criticism came, he wrote Either/Or and/or Both/And.

The book The Unrelieved Paradox has just come out in a second edition from Eerdmans. The final essay in the new edition was by Jean-Luc Marion, a fan of Bibfeldt, who flew from the Sorbonne to Chicago and back again, to deliver the annual Bibfeldt Lecture, held, of course, on April Fool’s Day.

All of which serves appropriately to prove Lincoln’s alleged observation that God must have had a sense of humor.

Kindly submitted in earnest honesty,

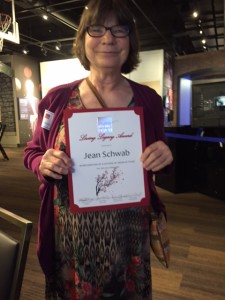

Jim Schwab

The Readings

Several of us throughout the day provided readings of former Midland Authors. As I noted above, I would have begged for the honor of presenting SMA founding father Vachel Lindsay, but I did not have to. The rest of the board and officers agreed almost as fast as I offered. I would also note, before going further, that SMA had founding mothers as well, among them Harriet Monroe and Edna Ferber. The list of those who saw fit to found this organization in 1915 is virtually a Who’s Who of Midwestern literary lights of the time.

But Vachel is a particular challenge for a modern presenter. A forerunner of today’s performance poets, his work was rhythmic, often accompanied by musical instruments, and so highly susceptible to public presentation that Lindsay became known for his “Poems for Bread,” which involved his bartering a reading of his work to some farm family in Illinois in exchange for a bed for the night and breakfast in the morning. His work was so close to the working-class fiber of the Midwest that long-time Socialist leader and presidential candidate Eugene Debs was a big fan. How do I know? Bernard Brommel, former SMA president and author, and long-time professor of speech and communications at Northeastern Illinois University, who wrote a book about Debs, told me so.

So how to get this right? I chose two poems by Lindsay, short enough to stay within my allotted five minutes while providing sharply contrasting views of the influence of religion in his life and career. First was “The Unpardonable Sin,” which I used as prelude to a blog post last fall. It is an angry anti-war poem written in the midst of World War One. Second was a celebratory poem, “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven,” meant to honor the founder of the Salvation Army after his death. The first could simply be recited, but required entering into the mood of its creation. The second took a little more: a search of the Internet to find renditions of “The Blood of the Lamb,” the tune to which it was set, to get the rhythm and tone right. Soon enough, I discovered a podcast of a recording of the song by none other than Woody Guthrie, in many ways a contemporary of Lindsay. That gave me the best possible sense of the underlying performance style that I could acquire.

That said, the second poem is designed for musical accompaniment by banjos, flute, and tambourines. I had none of these available for this modest performance, so I asked the audience to clap in rhythm when I raised my arms, and to stop when I lowered them for the softer stanzas. I am pleased to say that they accommodated me warmly, including Ald. Burke.

With that in mind, I provide links below to the two poems in their entirety for the edification and enjoyment of this blog’s readers. I enjoyed myself thoroughly; I hope you will too.

The Unpardonable Sin

General William Booth Enters into Heaven

Lindsay’s work is available in various reprinted editions, some of which I have read in their entirety. I acquired my Vachel Lindsay addiction in a high school creative writing class in the late 1960s. I have never submitted to rehab for this happy addiction, so rehab has done nothing for me.

P.S.: If this article inspires you to support the Society of Midland Authors, their website allows you to buy some great swag in the form of shirts, keychains, mugs, and tote bags. And you thought I was above this sort of appeal? 🙂

Jim Schwab