Have you ever tried to visualize yourself in a prominent, visible role other than whatever you do for a living? Can you see yourself accepting a Grammy, say, or racing across the goal line with a touchdown pass? Most of us at some point have some fantasy about our lives. Such fantasies are largely harmless things. They inspire us to aspire without making us delusional.

Sometime last night before the stroke of midnight in Chicago, some one of you became the 12,000th subscriber to this blog. I mention the point only because, as this audience grows, so grow the odds that someone out there can relate to what I am saying in a blog post like this, when I grow tired of discussing politics or public policy and just itch to let my imagination roam. I know I’m not the only one, as John Lennon once sang.

Several circumstances have converged to inspire this rumination. One is that I have needed to spend time this weekend on some serious technical writing in order to catch up on work I promised to do, some of which was forestalled Friday by family business. I want to break out of the rut. A second fact is that I have joined nearly the whole city of Chicago in pensively following the almost inconceivable set of daily triumphs this spring that have given our generally luckless baseball city the two best teams in Major League Baseball—at least so far, knock on wood, and may I not jinx either one by speaking too soon. When I’ve had the chance, I have watched both Jake Arrieta of the Cubs and Chris Sale of the White Sox as they have mowed down opposing hitters and built enviable records on the mound. I mean, between them, they have a 15-0 record this season and a combined ERA of about 1.0.

Why do I care? Back to the rumination—they are living a fantasy that I am only beginning to understand, now that I am far too old to hope to achieve anything like it. In fact, I am old enough to be their father. When I was their age, I was only beginning to overcome the intimidation in facing pitchers wrought by the fact that I needed thick glasses by the time I was ten, a story I rendered in my very first blog post on this site about four years ago. I did not understand how people threw curve balls at 90 miles per hour, and I certainly did not understand how anyone swung the bat fast enough to hit such pitches. Having never learned the rapid reactions that allow people even to face such pitchers, let alone hit home runs against them, I could only stand there dumbfounded as the ball whizzed past. It did not matter whether I swung. I was nearly 40 before I started to play competent intramural softball. By that age, most professional athletes have seen their best days and are on the way to retirement.

But that is not really my point. It was about then that my cognitive assets began to kick into gear, at least with regard to some sports, to notice from observation just how these athletes managed to do what they do. I started to follow the path of the ball closely, and the arc of the bat, and other central elements of professional baseball. I have come to realize what kind of arm or reflexes it takes to perform at that level. Even if I was never capable of realizing a daydream of launching a ball out of the park—and believe me, I never was—I at least began to realize how they did it, and the strategies behind the confrontation of hitter and pitcher. Because I have a better grasp of what is happening, I enjoy the game now more than I ever have in the past. I appreciate what Arrieta and Sale do in a way I never could before. I have become a student of the game.

That gets me to my real point. Well, sort of. We can be students of many things in our lives and benefit from it all, somehow. At the end of 2013, an exceedingly hectic year in which I racked up 23 business trips connected with my position at the American Planning Association, two more connected with teaching at the University of Iowa, plus some personal travel, I knew that something had to change. I had not gotten to my fitness club for weeks at a time, and I was wearing down. So I switched clubs to XSport Fitness and signed up to work with a personal trainer, having decided the additional expense would be more than compensated with renewed stamina and physical discipline. Then I had to wait about two months before I could start because, on New Year’s Day 2014 at a Barnes & Noble store, I pinched a shoulder nerve by carelessly tossing an overly heavy laptop bag on my left shoulder as I prepared to leave. That reinforced the logic of why I needed such training in the first place.

I have worked since then and made great strides in personal fitness, including, recently, a string of 150-second planks. More important, however, is what I have been learning through the trainer, Michael Caldwell, with whom I regularly discuss why I am doing what he asks me to do. I am thus gaining both intellectually, with a better understanding of physical fitness technique, and physically, by pursuing higher goals over time—and steadily achieving them. It is an important lesson in perseverance. I realize just how much work professional athletes must perform to condition themselves, no matter what natural talents they begin with. Fitness does not just happen.

It is not, however, as if I had never learned perseverance before. I have merely changed the setting or, to put it another way, added a new setting to those that were already familiar. And what I have learned in life is that loving what we do is what makes perseverance seem worthwhile and endurable. For athletes, it is literally the love of the game—that is not merely a phrase—and when that goes away, it is surely time to retire and find something else to do.

Two nights ago, Friday the 13th, my wife and I attended The King and I at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. We both loved the show. Jean, whose father was at one point in his life a music instructor, loves such musicals and enjoyed every minute of it. I mention it because I have never, in my entire life, tried to envision myself as one of the performers for such a show. I have never imagined that I have the kind of voice that it would take to impress a large audience, and my gift for music is marginal at best. For this, I was and will remain merely a spectator, a member of the consuming public. I cannot imagine myself enjoying the process of developing the necessary talent. It is not part of my rumination. I might add that, having purchased the tickets as a Mother’s Day gift, I should have anticipated that Friday the 13th would be a night in which, after the show, we would have to race five blocks through a downpour to the Blue Line to go home, getting soaked even with a raincoat and umbrella between us. (Forget the taxi line at the Lyric; it was hopeless.) I have never daydreamed about becoming a meteorologist either, not even a handsomely paid one on television. Not my thing. But I digress.

Any savvy reader will grasp by now that I am writing this article because I did find my calling, and I did persevere in developing my skills, however convoluted the path I may have taken in life. As early as the third grade, I was attempting to write science fiction stories. I dreamed of publishing them, although today I am glad that those early manuscripts have mercifully disappeared, their pages rotting in some landfill in northern Ohio. The love of writing took many forms over the years, but it has never left me. In high school, I used my electives to include one-semester courses in both journalism and creative writing. I was a co-founder of the Brecksville High School Writers Club. I began college as an English major, switching to political science only as I became drawn to the turmoil of the 1960s and the elusive prospect of somehow changing the world. I wrote for the student newspaper, sometimes well, sometimes poorly. Later I wrote a handful of op-eds for the Plain Dealer in Cleveland, and then I moved to Iowa, and continued to write and publish there. I found my way into graduate school at the University of Iowa, and not satisfied simply to get a master’s degree in urban and regional planning, I prolonged my academic efforts by adding a second master’s in journalism. Then came a fateful day when I had to decide on a master’s project in journalism, and I decided that if I had to do such a project, it ought to become a book. Three years after graduation, it emerged between two covers from the University of Illinois Press as Raising Less Corn and More Hell, an oral history of the 1980s Midwest farm credit crisis. At 38 years old, I finally found myself being reviewed in the New York Times. I had envisioned myself as a published author and cared so much about learning the craft that I never noticed just how much perseverance, how much sweat, how many wrong turns turned around I had poured into this and other projects to reach this plateau. Only in looking back do I realize the level of effort I sustained.

Like Arrieta and Sale, though certainly not with their level of fame, I loved my game and was passionate about succeeding.

The great thing about writing is that, at 66, although my energy may flag more than it did 30 years ago, I can keep going. I will not wear out my arm on the keyboard. Studs Terkel published his last book at the ripe age of 94. I can keep getting smarter about my craft without worrying about its physical toll, at least for the foreseeable future. As for that other degree? It built on my background in political science, in a way, and more importantly, it gave me something truly substantive to write about. I didn’t just want to write. I had something to say. I had another passion.

If you are one of my young readers, find your dream. Persevere with it. Trust me, it is worth it. And if you are older, well, hang in there. Life can still be beautiful if you have a purpose.

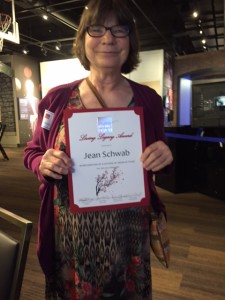

By the way, as for that mention of Mother’s Day: By the time I finished graduate school, I had met my wife, and we got married. I learned about passion and purpose from her too. She is retired now, but her passion was teaching. And she was happy last week. At a luncheon for its retirees, the Chicago Teachers Union gave her a lifetime achievement award for her activism. I have seldom seen her more pleased.

By the way, as for that mention of Mother’s Day: By the time I finished graduate school, I had met my wife, and we got married. I learned about passion and purpose from her too. She is retired now, but her passion was teaching. And she was happy last week. At a luncheon for its retirees, the Chicago Teachers Union gave her a lifetime achievement award for her activism. I have seldom seen her more pleased.

Jim Schwab