In an era of congressional gridlock, with so little productive activity coming out of Washington that many people have begun to wonder if federal government is good for anything, the best models often work quietly in the shadows—and they may not even work primarily out of Washington. They work around the country, in the hinterlands, and along the coasts. They may even have odd names like Digital Coast, suggesting the marriage of digital technology with environmental and coastal planning needs. This is the story, in my own idiosyncratic fashion, of one such model.

Just last week, I spent three days in Milwaukee at a meeting of the Digital Coast Partnership, which is affiliated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), an arm of the U.S. Department of Commerce. Digital Coast is a program of NOAA’s Coastal Services Center (CSC), based in Charleston, South Carolina. CSC is in the process of merging with the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management (OCRM), in order to form a single coastal operation within NOAA. OCRM has been responsible for administering the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA), a piece of legislation passed in 1972 that supports a cooperative approach to better coastal resource management between the states and the federal government. But all this may be more bureaucracy than most people want to know, so let’s cut to the chase.

Overburdened local governments and regional planning agencies in coastal areas often do not have all the resources they may need to do a thorough job of planning intelligently for the future of the nation’s coastline. Under the CZMA, that coastline includes all areas along the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic Oceans, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Great Lakes, including estuaries and bays like the Chesapeake Bay. In addition to tens of thousands of miles of coast, this area also is home to 39 percent of the U.S. population and many of our largest cities, including Boston, New York, Miami, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, and Honolulu. In all, some 30 states and five territories are included in the Coastal Zone Management Program.

Managing coastal resources is a delicate balancing act that includes planning for many environmentally sensitive areas, economic powerhouses and attractive tourist destinations, and major ports that drive trillions of dollars in economic activity. It requires advanced planning tools, knowledge of both economics and environmental science, and an understanding of the demographics of these areas, which can be very diverse. Many of our coastal cities like New York have been historic points of entry for many of the immigrants who have subsequently built so much of the modern United States.

Providing a modest suite of online tools and resources to make that job just a little easier at the local level is the job of Digital Coast. But now I am going to dive into the truly interesting part of this whole story—the emergence of the partnership.

Early in 2010, I was approached by representatives of NOAA on behalf of the Digital Coast program to gauge the interest of the American Planning Association in joining what was then a group of five national organizations that comprised the Digital Coast Partnership. These were the original team that had been assembled to help NOAA assess the usefulness of the resources it was creating and to reach deeply into the user communities for those resources to spread the word that this online resource existed. Those five organizations were The Nature Conservancy, National States Geographic Information Council, Coastal States Organization, Association of State Floodplain Managers, and National Association of Counties. Within the first year, they determined that something was missing—contact with urban planners. So they decided to invite us to join them. By July 2010, we signed an agreement to do exactly that, and we have never looked back. At the same time, as Nicholas J. (“Miki”) Schmidt, CSC’s Division Chief for Coastal Geospatial Services, likes to say, they could not be happier that APA joined.

What is the point of this partnership? It is long past the point in American history where a federal agency can afford to develop a new resource for local government without having some means to determine whether what they think will be useful actually is what is most useful to practitioners. Collaboration is more the order of the day. Find the people who will have to make best use of the tools, resources, and data you want to create, and ask whether what you have in mind is as useful as it could be, or even useful at all. If those user groups can vet your product and tell you seriously that, with perhaps this change or that tweak, what you are considering developing would be beneficial to local officials, planners, and resource managers, then go for it. If not, rethink it. In the end, what emerges is a highly productive symbiotic relationship in which those who must make better coastal planning and resource management happen at a local and regional level have a voice in the kinds of tools, data, and resources that may make their jobs easier.

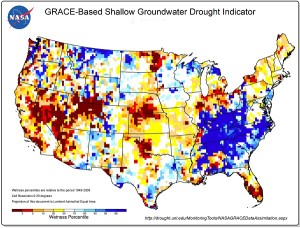

As logical as all that sounds, the case for this model becomes even more compelling in the context of climate change. Our evolving climate, driven by the relentless addition of greenhouse gases from modern transportation, industry, and agriculture, among other, lesser sources, has greatly complicated long-term prediction models, particularly as they affect the modeling of future natural hazards such as flooding, drought, heat waves, and coastal storms. Unfortunately, at the same time, NOAA, as the governmental entity providing or funding much of the science of climate change, has had a target on its back in some of the oversight committees in Congress, especially those now chaired by skeptics of climate change. Some of these members of Congress seem virtually impervious to the mountains of evidence produced both domestically and internationally, to the nearly unanimous consensus behind the theory of climate change among climate scientists, and to the many reports that have supported climate concerns. We live in a strange universe in which science itself has become suspect among some in the halls of Congress, even as the need for scientific insights into complex planetary processes becomes more profound, and the long-term economic consequences of any missteps become ever more frightening. Several recent reports (e.g., Risky Business) and books suggest that we are playing Russian roulette with the world’s economic future.

But again, I digress. I am trying to focus on the value of Digital Coast and the partnership that supports it.

So back to Milwaukee. Our three days there were the latest iteration of a series of twice-yearly meetings of the partners and their NOAA compatriots in an ongoing quest to advance the program and enhance its value, something the partnership has been doing for more than five years now. In the past year, we added two new organizations that have embraced the partnership with enthusiasm: Urban Land Institute, and the National Estuarine Research Reserve Association (NERRA). The latter may sound like a mouthful; it is a relatively small organization, but it is important. Its members constitute the staff of a nationwide network of national estuarine research reserves, where services are provided to monitor and learn the value of coastal and tidal estuaries, to provide educational and environmental services, and to help us all learn what a biologically rich system these estuaries provide if properly cared for. The coast is an intricate fabric of ecosystems. NERRA members help us understand its essential value.

The first of our three days in Milwaukee was devoted to a rather intriguing experiment by ASFPM, which hosted a No Adverse Impact seminar for the Great Lakes, held at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus. ASFPM has been leading the development of a Great Lakes Coastal Resilience Planning Guide, to which APA contributed through research support and outreach. This one-day seminar, attended by about 50 people, allowed practitioners who were not directly allied with Digital Coast to mix with the representatives of partner organizations. It also let the partners learn how Digital Coast concepts and tools might be more useful to their members and constituents. I spoke at this seminar in the morning, offering a comparison of two Great Lakes coastal counties and their varying governance systems in an effort to assess their progress toward achieving resilient coastal communities. I also fed into a later presentation about a new “no build” ordinance in St. Joseph, Michigan, requiring that new development in a beachfront residential area be set back far enough to account for the inevitable rise and fall of lake levels and to prevent the rush to build closer to the shore during periods when the lake had retreated.

That question ties directly to one of the major differences between the Great Lakes and oceanic coasts, where sea level rise is the dominant long-term concern. Increased weather variability in the Great Lakes region, as a result of climate change, is likely only to exacerbate long-term oscillations in lake levels, not to raise water levels. Periods of drought and increased temperatures may accelerate evaporation of Great Lakes waters, with considerable variation among the lakes, while heavy precipitation may add to lake levels, and extreme outcomes like the past winter’s polar vortex may extend ice cover and raise lake levels. It is a complex picture. Climate change entails mostly warming most of the time, but with serious variations from the norm on many other occasions. If there is one thing we can count on, it is increased volatility. But that all makes regulating coastal development on the Great Lakes very tricky business because many public officials and much of the public share relatively short memories and short-term perspectives on the associated hazards. We all need a greater tolerance for complexity if we are to understand the problems that lie ahead.

With the seminar behind us, the two-day meeting (August 20-21) involved our usual packed agenda of discussions among more than 20 representatives of NOAA and the partner organizations. We discussed the improvements in the Digital Coast website, how we were going to fund future operations, how we could collaborate on future projects, and how all the work would get done. The NOAA personnel appear to have had wonderful training in collaborative leadership, in ensuring that every partner’s input is valued, and in translating the resulting information into better governmental resources to aid the practitioners who need to make crucial local decisions about coastal development, environmental protection, the protection of jobs that depend on a healthy coast, and other vital subjects. That rubs off on the partners, and the result is a rather seamless web of ideas, contributions, testing, and feedback that serves to enrich what Digital Coast has to offer. This includes tools to visualize impacts of sea level rise, coastal habitat conservation, and the economic value of coastal activities such as commercial fishing, recreation, shipping, and tourism.

So go ahead; click on Digital Coast to visit the website and test-drive the tools, data, and resources and find out why we use the slogan, “More than just data.” Oh, and did I say “we”? Yes. It’s not just another federal program. It is a federal program that wants to hear from you and actually values input and feedback. Digital Coast has taught me a great deal. It has given me reasons to be hopeful about new collaborative models for providing federal services to the public.

Jim Schwab