I grew up near the shores of Lake Erie, in suburban Cleveland. After a seven-year stint in Iowa and Nebraska, I ended up in Chicago, where I have lived since 1985. The Great Lakes have been part of my ecological and geographic consciousness for essentially 90 percent of my lifetime. As an urban planner, that means I am deeply aware of their significance on many levels.

It will surprise no one, then, that as a planner who has focused heavily on environmental and natural hazards issues, I have been involved in projects aimed at protecting that natural heritage. As manager of the Hazards Planning Center at the American Planning Association (APA), I involved APA as a partner with the Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM) as ASFPM developed its Great Lakes Coastal Resilience website with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) support. Later, I prepared a successful grant for support from NOAA’s Sectoral Applications Research Program for a project on integrating climate change data into local comprehensive and capital improvements planning. In that project, APA collaborated with the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and the University of Illinois. That project, which involved work with five pilot communities in the Chicago metropolitan area, was (and still is) ongoing when I left APA at the end of May 2017. The aim was to develop applicable models for such planning for other communities throughout the Great Lakes region.

It is thus always encouraging to see others pick up the same mantle. It was hardly surprising that the Environmental Law & Policy Center (ELPC), a long-time Chicago-based staple of the public interest community, would see fit to do so. On March 20, in concert with the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, ELPC released “An Assessment of the Impact of Climate Change on the Great Lakes,” with 18 scientists contributing to the 74-page report. I spoke two weeks later with Howard Learner, the long-time president and executive director of ELPC, about the rationale and hopes for the report.

The impact of adding one more report to the parade is cumulative but important. Learner explained that national studies, particularly the National Climate Assessment, mention regional impacts of climate change, but that drilling down to the impacts on a specific region and making local and state decision makers aware of the issues at those levels was the point. Thus, he asked Don Wuebbles, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Illinois and a science adviser to ELPC, to assemble a team of experts for the purpose. Wuebbles recruited most of the team, with the goal not only of identifying problems but of developing or pinpointing solutions. Repeatedly, Learner emphasized the public policy role of ELPC as a “problem-solving” institution. The intended audience was governors, provincial ministers, congressional delegations from Great Lakes states, and other public officials, providing them with an assessment of the state of the science concerning the Great Lakes.

I won’t even attempt to review all the data in the report, but certain points are essential to an adequate public understanding. For one, the Great Lakes are simply huge and constitute a very complex ecosystem in a heavily populated region of more than 34 million people in the U.S. and Canada, the vast majority of whom repeatedly express support for protection of the Great Lakes in public opinion polls. It is the largest freshwater group of lakes on the planet, and second largest in volume. It is a binational ecosystem that demands cooperation across state, provincial, and national boundaries. It is home to 170 species of fish and a $7 billion fisheries industry. It has long been home to one of the most significant industrial regions of both nations. What happens here matters.

The term “lake effect” is most often associated with the Great Lakes because their sheer mass has a measurable impact on local and regional weather patterns. Winds pick up considerable moisture that often lands downwind in the form of snowstorms and precipitation. For instance, any frequent visitor of farmers’ markets along the Great Lakes is likely to be aware of western Michigan’s “fruit belt” offerings of apples, cherries, pears, and other crops dependent on the lake effect.

Figure 3. Observed changes in annually-averaged temperature (°F) for the U.S. states bordering the Great Lakes for present-day (1986–2016) relative to 1901–1960. Derived from the NOAA nClimDiv dataset (Vose et al., 2014). Figure source: NOAA/NCEI (Both images reprinted from report courtesy ELPC.

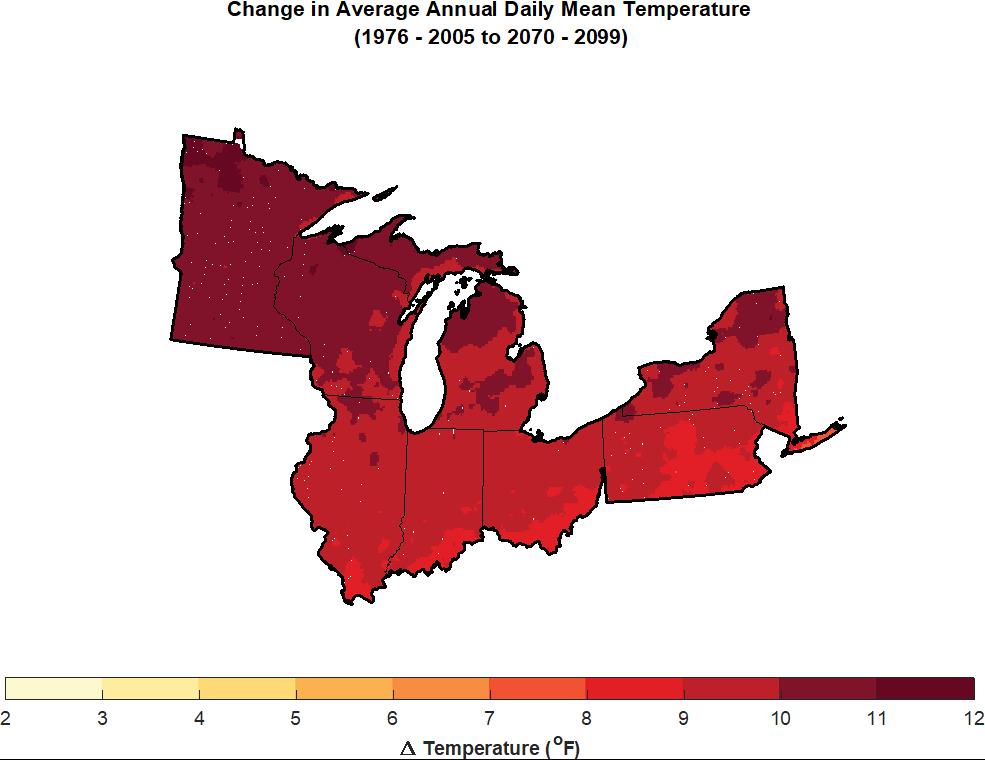

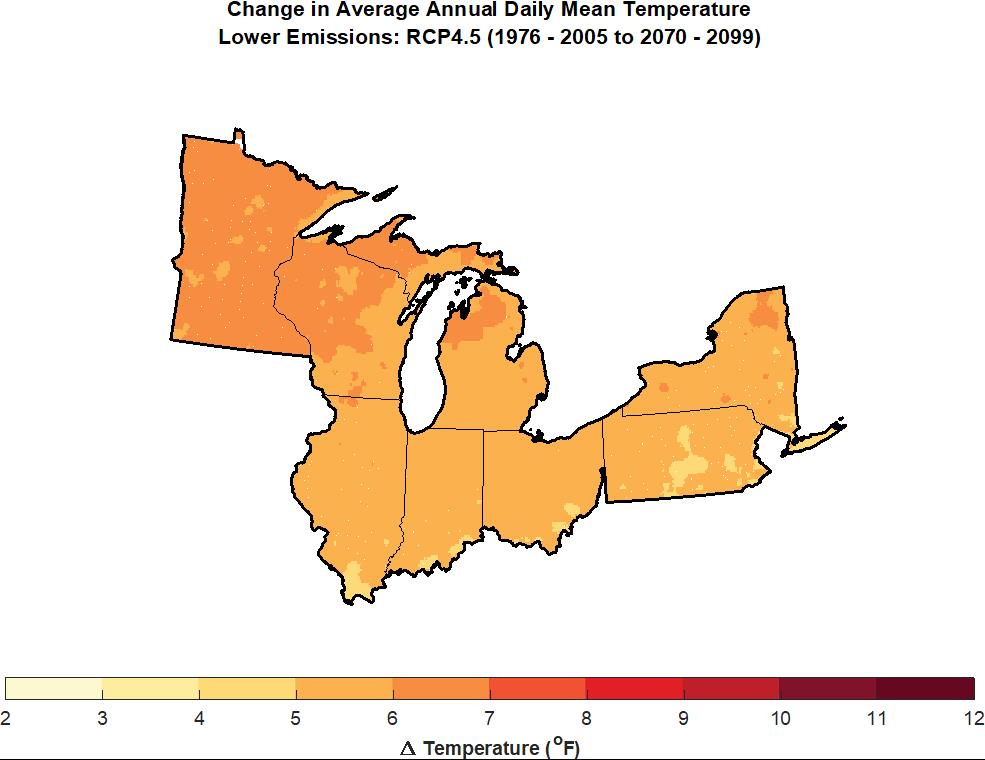

Figure 4. Projected change in annually-averaged temperature (°F) for U.S. states bordering the Great Lakes from the (a) higher (RCP8.5) and (b) lower (RCP4.5) scenarios for the 2085 (2070-2099) time period relative to 1976-2005. Figure source: NOAA/NCEI

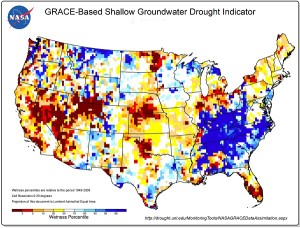

The lake effect, of course, is a part of the natural system in a region carved out of the landscape by melting glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age. Recent climate change is another matter. The region has already experienced a 1.6° F. increase in average daily temperatures in the 1985-2016 period as compared to the 1901-1960 average. Those increases are expected to accelerate over the remainder of this century. It is not just temperatures that change, however, because changing weather patterns as a result of long-term climate change result in altered precipitation patterns. Summer precipitation is predicted to decline by 5 to 15 percent, suggesting some increased propensity for drought, while winter and spring precipitation will increase, producing an increased regional propensity for spring flooding. Increased intensity of major thunderstorm events will exacerbate the vulnerability of urban areas to stormwater runoff, resulting in increased “urban flooding,” often a result of inadequate stormwater drainage systems in highly developed urban areas. That, in turn, has huge implications for municipal and regional investments in stormwater and sewage treatment infrastructure. In addition, heat waves can threaten lives and public health. Public decision makers ignore these implications at the fiscal and physical peril of their affected communities.

Among those impacts highlighted in the report is the increased danger of algal blooms in the Great Lakes as a result of changing biological conditions. The report notes that the largest algal bloom in Lake Erie history occurred in 2011, offshore from Toledo, Ohio, affecting drinking water for a metropolitan area of 500,000 people.

There is also danger to the stability of some shoreline bluffs, an issue highlighted on the Great Lakes Coastal Resilience website, as a result of reduced days of ice cover during the winter. While less ice cover may seem a minor problem to some, in fact it means changes in water density and seasonal mixing patterns in water columns, but it also means the loss of protection from winter waves from storm patterns because the ice cover prevents those waves from reaching the shore until the spring melt. The result is increased shoreline erosion.

All of that harks back to the central question of my interview with Learner: What do you hope to achieve? “The time for climate action is now,” he insisted, noting that the Trump presidency has been “a step back,” making it important for cities and states to “step up with their own climate solutions.” Learner hopes the report at least provides a “road map” for governors and Canadian premiers to focus their actions on the impact of climate change on the Great Lakes, such as “extreme weather events.”

Curiously, one arena in which new action may be possible is the city of Chicago itself, which on April 2 elected a new mayor, Lori Lightfoot. Media attention has focused on the fact that she is both the first gay mayor and the first African-American female mayor in the city’s history, but equally significant is her history as a former federal prosecutor who campaigned against corruption. Learner notes that outgoing Mayor Rahm Emanuel convened a Chicago Climate Summit in November 2017, and that ELPC is now “looking to Mayor Lightfoot to step up Chicago’s game” to benefit both the local economy and environment with a stronger approach to climate change.

The same can be said, of course, for numerous other municipalities choosing new leadership and for the new governors of the region, including J.B. Pritzker in Illinois. They all have much work to do, but an increasing amount of research and guidance with which to do it.

Jim Schwab