At first, the music was minimal or even silent. Voices from the twelve-member Adrian Dunn Singers, spread across the back and sides of the sanctuary of Augustana Lutheran Church of Hyde Park, simply announced a date in 2021, beginning on January 1, followed by the names of specific homicide victims of that day, mostly of gun violence. Steadily, they moved through the calendar year, each ten seconds in the score representing one day. Being the type of person who cranks numbers quickly in his head, I could not resist doing the calculation and determining that the pace stated in the program would consume just over an hour. A good length, I thought.

The weeks and months rolled by with the haunting music steadily asserting itself, but it was not lyrical. It sounded incantational, voices from the throat at various pitches as particular singers chimed in, based on troubadour melodies. This music induced, as my wife noted, meditative moods, or in my case, a growing and palpable sense of the waves of humanity slaughtered on the city’s streets and elsewhere, nearly 800 according to the Chicago Police Department, the worst year since 1994. For me, it was beyond a feeling of grief; it was an emotion that encompassed a profound sense of the waste of human lives, many of which never had the opportunity to contribute their talents to the city or our nation—just this gulf between what could have been and what we have become.

This July 23 premiere of “Memoria de Memoria,” a composition by composer Christophe Preissing, was requested by Rev. Nancy Goede, the parish pastor of Augustana, to honor the first anniversary of the death of Keith Cooper, 73, a member of Augustana killed last summer in a botched carjacking just two blocks away. Unanticipated was the punctuation of this year’s Chicago summer by the mass murder of seven people during a July 4 parade in nearby Highland Park, Illinois, a north shore suburb, in which about 30 other people were wounded, including an eight-year-old boy who now is paralyzed from the waist down. The alleged perpetrator, Robert Crimo III, was arrested later that night by police who found him in his car in Lake Forest. Highland Park, which quickly became the latest focus of national news on the problem of assault weapons and mass violence, will never be the same. There will always be before and after for Highland Park. For many violence-plagued neighborhoods in Chicago, however, there is always the frightening tension of now, of the gang that can’t shoot straight, of every day that we fail to get the guns off the streets and fail to find ways to give countless youths, many of them young Black men, some positive sense of purpose in life.

In the meantime, art can help us express our anger, our grief, our moral passion. That was the power of the Saturday evening presentation, of letting us experience all that emotionally through exquisitely crafted but distinctly unconventional music. Audience members had the opportunity to approach the altar, light memorial candles, and remember those whose memories they cherish as unique human beings whose light was extinguished prematurely through violence.

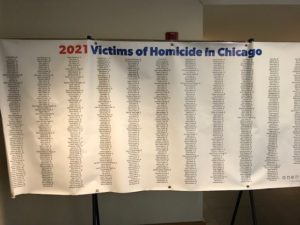

Readers may note in this blog post the absence of photos of the concert itself. It did not seem appropriate to shoot photos of or during the performance, although I share two that I took later and consider important. One shows the fabric art of Michele Makinen, who died of cancer earlier this year but lived in Chicago since 1974. “Guns: A Loaded Conversation” hung on the sanctuary wall, exhibiting the intricate workmanship Makinen brought to her response to the shooting of innocent children at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, in December 2012. The flag quilt became part of a traveling exhibit the following year. The other photograph shows the almost complete list of victims of violence in 2021 in the city of Chicago. I say “almost” because I was told it may not have included some people injured in late 2021 who died earlier this year after the poster was completed.

The other photograph shows the almost complete list of victims of violence in 2021 in the city of Chicago. I say “almost” because I was told it may not have included some people injured in late 2021 who died earlier this year after the poster was completed.

Let me just note, in closing, that the Hyde Park community and Augustana, in celebrating the life of Keith Cooper, whom I memorialized in a blog post a year ago, have created the Keith Cooper Fund to “provide monetary awards to promising young people between the ages of 16 and 26 who live in one of the neighborhoods of the near South Side of Chicago.” They may use the grants to seek training in a vocational or licensed trade; grow a startup business; or launch a career in jazz or other performing or fine arts. Keith Cooper represented all those aspirations and more, seeking to help those around him. Donations can be made online at www.augustanahydepark.org. You can contact the Keith Cooper Fund at keithcooperfund@gmail.com.

Jim Schwab