Hillsborough County is a dense metropolitan area, anchored by the city of Tampa. Tampa and nearby St. Petersburg, in Pinellas County, sit on opposite shores of Tampa Bay, a 400-square-mile expanse of water connected to the Gulf of Mexico. Across that gap sits the Sunshine Skyway Bridge, a magnificent and scenic section of I-275. On a sunny day, it displays coastal Florida in all its glory.

Eugene Henry, like anyone else, enjoys those sunny days, but he also worries about what may happen when the region suffers inclement weather. As Hillsborough County’s Hazard Mitigation Program Manager, it is his job to think about how well the area will fare under the impact of natural and other disasters, which can include hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, sinkholes, and wildfires. At least the first two are complicated by sea level rise, and one can easily argue that climate change in a broader sense may well influence the damage from wildfires. For those uninitiated in the particulars of Florida’s natural environment, wildfires are a recurring feature. In what is ordinarily such a lush environment fostered by rain and abundant sunshine, it takes only one drought year amid high heat to turn dense vegetation into a tinderbox. It has happened before, repeatedly.

But the biggest concern, by far, is the arrival of the Big One, the high-intensity hurricane that the county readily admits it has escaped in recent decades. In its Post-Disaster Redevelopment Plan (PDRP), the county states forthrightly that this is merely a matter of good fortune and that planners fully understand that the day will surely come—and that they had best be ready for it. Disaster resilience in the face of hurricanes is not a matter to be taken lightly with 158 miles of shoreline along Tampa Bay, numerous rivers and streams, and numerous vulnerable, low-lying areas. Absent serious attention to mitigation, damages from a Category 4 or 5 hurricane, or one like Harvey that stalls and dumps voluminous rain on an urban area, could become catastrophic.

But Tampa and Hillsborough County have been very fortunate. The last Category 3 hurricane struck the area in 1921. What may have been a Category 4 struck in 1848, though wind speed measurements were primitive at the time, and the U.S. had no official records yet. According to the county’s Local Mitigation Strategy, that storm “reshaped parts of the coast and destroyed much of what few human works and habitation were then in the Tampa Bay area.” Tides rose 14 feet. Tampa was still a small city then, and Gene Henry wonders about the staggering losses that might occur with a comparable event today.

I had long wanted to visit the area to see in person how these issues are being addressed. I have known Gene for a long time, and I have read the county’s PDRP, an extensive document laying out the county’s preparations for recovery from disasters. But I had never been to Tampa. As the result, however, of a personal invitation from a high school classmate, David Taylor, who now lives in Sarasota, my wife and I flew to Tampa February 20 and stayed with Dave and his wife, Linda, for five days. Sarasota is about one hour’s drive south of Tampa. As part of the trip, I arranged to meet with Gene the day after we arrived and tour the county to see the hazard mitigation projects underway there. I also delivered a one-hour lecture the following afternoon in West Palm Beach, on behalf of Florida Atlantic University, as part of a two-hour program that included a panel discussion following my talk on “Recovery and Resilience: Facing the Disasters of the Future.” Not one to skip a learning opportunity, Gene drove four hours from Tampa to attend the program.

But back to Hillsborough. My wife and I met Gene at the county’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) around mid-morning, hopped in his county truck, and took off. Our first stop was the Florida Center for Design + Research, housed in the School of Architecture + Design at the University of South Florida (USF), Gene’s graduate alma mater. The school features an urban planning program where he wanted us to meet Professor Brian Cook. Planning students often take studio classes, which involve design or research work on real-life community problems. Students learn to define a community design or policy issue, work with clients, and try to produce solutions that will be of some practical value to the community they are serving. They typically work in teams. In this case, students were applying geographic information system (GIS), or mapping, skills to determine areas of high vulnerability to flooding and sea level rise in less affluent neighborhoods. Gene’s county office collaborates with USF instructors to identify areas of practical concern for the students’ work. The photos show some of the design work the students have done, the best of which is often displayed in poster sessions at state and national professional planning conferences.

The most encouraging aspect of that visit was, for me, the mere fact that the students are engaging with such a pressing problem. I have researched the issue of hazards and climate change in the planning curriculum for both undergraduate and graduate degree programs in urban planning, and most such programs are lacking in this respect, a situation that is disserving the planners of tomorrow who must be well trained to come to grips with these challenges in whatever communities they end up serving. But a growing number of students are getting such training—I have myself been teaching such a course at the University of Iowa since 2008—and southern Florida is as good a laboratory as they could wish for. To see collaboration between a county agency and USF graduate students and faculty is a most welcome note.

But Gene had other places to take us in the afternoon, besides, that is, the Cuban-themed La Teresita restaurant where we ate lunch—a place I am willing to recommend if you ever visit Tampa.

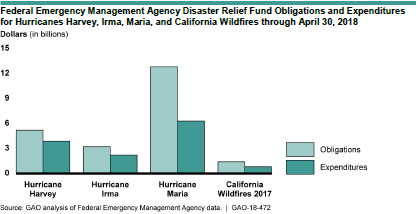

First up in the afternoon was the University Mall area north of downtown Tampa and just east of I-275. This involves a stormwater management and flood-mitigation project in an area subject to a certain amount of repetitive loss, meaning that the same properties continue to suffer periodic flood losses. The project removed structures while creating additional areas for stormwater storage and reshaping a natural area known as Duck Pond, thus creating a system for stormwater conveyance. This includes a large stormwater pump that transfers slow-moving stormwater to areas further downstream and, in due course, to a reservoir owned by the City of Tampa. Before this project was initiated, storms used to inundate multifamily apartment buildings, Gene says, as well as a nearby assisted living facility. How does the county pay for all this? He credits a combination of local funds, which is certainly not unusual, and federal money in the form of Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) funds. The latter are available as part of an overall recovery package after a Presidential Disaster Declaration, but require that purchased properties, once cleared, remain in perpetual open space. The point is to ensure that a vulnerable area is not redeveloped, thus perpetuating the problem.

At 132nd Street, also in Tampa, another flood-mitigation and stormwater management project presents a very different appearance. This too was subject to repetitive loss and required protection from urban flooding, which is typically the result of poor stormwater drainage in developed areas. The problems can include poor water conveyance from one area to the next—the nearby highway provided an impediment to drainage—and high levels of impervious surface, meaning coverage with concrete and structures that limit percolation of water into the soil. In this case, a small subdivision suffered repetitive flooding even with small storms. Here also, the county acquired homes with HMGP funds, which are dispensed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The streets were removed, and stormwater ponds were added.

This was a location where the county’s partnership with USF paid dividends. Researchers analyzed which plants were best at removing nitrogen and other chemicals common in stormwater runoff in order to clean up the water before it reaches Tampa Bay. Henry says this project was made possible through a combination of local and HMGP funds in combination with federal Community Development Block Grant entitlement money.

I included the chain link in my photo to show that the solution may not be complete. After all, chain link fences are intended to limit access. What consideration, I asked, had been given to eventually converting this cleared area to some sort of public park and thus facilitating a public benefit? There can be challenges in part because of pollution cleanup and other public safety factors. Gene readily admitted he would love that solution, but it may take time. The adjoining neighborhood must be comfortable with that use, which can involve solving various site-related problems. A nearby church might be a potential ally, serving as a patron and watchdog, but reaching agreement about solutions and responsibilities, including ongoing maintenance and supervision, takes time. And only time will tell whether such a solution materializes with the support of local public officials.

Some projects assist a single homeowner with a stubborn problem. This is often the case with homes that are elevated, a common site in parts of the Southeast, where coastal and riverine flooding can wreak havoc with homes in vulnerable locations that do not necessarily require buyouts and relocation. That was the case near Rocky Creek, where a homeowner rebuilt a structure elevated three feet above base flood elevation (BFE) using a combination of private funds and a Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grant from FEMA. The result is living space that is better protected when flood waters surround the lower level.

The same story occurred at a home near the Alafia River, where another homeowner was elevated three feet above BFE, using the same combination of funds.

Gene also shared with us an interesting strategy at a frequently flooded and highly vulnerable modular home park, where an area had been cleared of its former homes to allow repopulation with recreational vehicles (RVs). The logic is that, when flood warnings arrive, RV owners will be able, unlike those with more stationary modular homes, to simply drive off the site to safer areas until the emergency subsides. The initiative, Gene says, was taken by the park’s new owner (which owns other parks nationwide), which identified no more permanent structures in the floodway as part of its compliance strategy after the most recent flooding event in the area.

Finally, we returned to learn a little about the EOC. We visited what is often known in such centers as the “war room,” where designated officials meet to discuss and establish strategies for dealing with an emergency of any sort that activates the emergency operations plan. In the photo, each chair is designated for a specific official, with groups of people with related tasks seated in color-coded sections of the room. Many such EOCs are much smaller, but Hillsborough County is very urban and populated, and the needs are complex and interrelated. It is expected that those involved will arrive with authority to respond to the disaster, to indicate what they are and are not capable of doing as part of the overall response to disaster. It is not a place where one expresses a need to go back to another office and “find out.”

Ready to relax and enjoy a drink and a snack, we followed Gene down the highway to the Sunset Grill at Little Harbor, which has a beautiful view of the bay. At dusk, numerous people followed a daily ritual of photographing the sunset over the water. Tourist attraction it may be, as well as a local watering hole, but the surrounding area has a significant mangrove forest and salt-bed areas that were preserved as open space using Environmental Land Acquisition Funds from what Gene describes as a “locally instigated preservation program.”

And so, with the sun declining in the west, we sat at an outdoor table and hashed over the world’s problems, and sometimes our own. One point that seems clear to me is that Hillsborough County has a great deal to offer to other jurisdictions, just as it has undoubtedly learned a great deal as well—one reason both he and a resident scholar and Japanese graduate student from the University of Illinois, Kensuke Otsuyama, planned to drive to West Palm Beach the next day to hear my presentation. Although there is sometimes a tendency for local governments to become more insular, to allow fewer opportunities for employees like Gene to share and exchange information in professional forums and conferences, this, I think, is always a mistake. The growth in the value of what someone like Gene does lies in this fruitful sharing of experience and perspectives that such opportunities allow, and I hope that will continue, for certainly Gene made my day by sharing his time to allow me to learn and to share with the growing readership that follows this blog.

Supplemental Comment:

Although the hearing was held today, making live streaming a moot point, significant written and recorded testimony on hazard mitigation and climate resilience issues occurred before the U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing, and Urban Development. Yesterday, the following link was made available from several sources including the American Planning Association (APA) to provide access to this testimony and information:

Representatives from APA, PEW, Houston Public Works,

Rutgers University, and the Town of Arlington, MA are delivering testimony to

the Transportation and Housing and Urban Development (THUD) congressional

subcommittee tomorrow, March 13th at 10:00 a.m. EST. THUD, a part of

the House Committee on Appropriations, writes laws that fund the federal

government’s important responsibilities. The testimony is available for

streaming here:

https://appropriations.house.gov/legislation/hearings/stakeholder-perspectives-building-resilient-communities

APA will submit written testimony that will be put into the Congressional

record. The testimony will be available on APA’s website tomorrow.

Jim Schwab

Sustainable City Network will host a 4-hour online course Aug. 21 and 22 for anyone responsible for initiatives related to resilience and disaster recovery planning. In the first 2-hour session, we’ll review the overall concept of recovery planning and the need for widespread involvement by various sectors of the community. The second segment will walk participants through information gathering, assessing the scale and spectrum of the disaster, and how to involve the public in meaningful long-term recovery planning. Instructor James Schwab, FAICP, is a planning consultant, public speaker and author who has taught since 2008 as adjunct assistant professor in the University of Iowa School of Urban and Regional Planning, with a master’s course on “Planning for Disaster Mitigation and Recovery.” Attend live or via on-demand video. Cost is $286 when purchased by Aug. 3.

Sustainable City Network will host a 4-hour online course Aug. 21 and 22 for anyone responsible for initiatives related to resilience and disaster recovery planning. In the first 2-hour session, we’ll review the overall concept of recovery planning and the need for widespread involvement by various sectors of the community. The second segment will walk participants through information gathering, assessing the scale and spectrum of the disaster, and how to involve the public in meaningful long-term recovery planning. Instructor James Schwab, FAICP, is a planning consultant, public speaker and author who has taught since 2008 as adjunct assistant professor in the University of Iowa School of Urban and Regional Planning, with a master’s course on “Planning for Disaster Mitigation and Recovery.” Attend live or via on-demand video. Cost is $286 when purchased by Aug. 3.