It has always amazed me how much time and energy has been wasted, particularly in the U.S., on the denial of climate change in the face of so much scientific evidence. Sea level rise is a directly measurable phenomenon. So are changes in precipitation patterns over time. The fallback denial position, once the data are made clear, is that we do not know what is causing the change that we see, and therefore it is pointless to point to human influence on the environment. This, too, is of course nonsense because the theory behind the impact of greenhouse gases on warming temperatures has been with us for more than a century and has been validated for several decades. Yet, in the world of politics, the silliness goes on. And on.

One intriguing aspect of this denial is that distance from the problem seems to lend itself to a greater disposition toward denial. It is easier to ignore a problem that does not confront you visibly and directly. This distance need not be geographic; it can also be social and economic. Those near the seacoast with greater wealth and the ability to protect their property may not feel the pain of increased flooding and sea level rise nearly as much as poor homeowners who have fewer options to move or rebuild. For the same reason, if one can avoid loaded political language and discuss practicalities, it is possible to get many farmers to observe that growing seasons have grown longer, droughts have grown drier, and that something has surely changed in recent decades. As the saying goes, it is what it is.

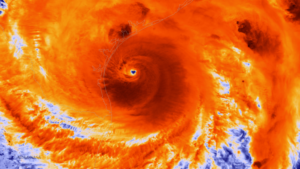

Elizabeth Rush will not let us forget what is. In Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, she gently but firmly seizes our attention to lead us through coastal communities that are already experiencing the ravages of sea level rise. She does not focus on projected damages or what may happen in three generations. She speaks powerfully, poetically, lyrically about what happens to people in communities that have depended on coastal ecosystems for generations but now must face the prospect of relocating or abandoning the places to which they belong, of which they have been an organic part. We visit communities in Florida, Louisiana, San Francisco Bay, and New England that are witnessing permanent change in their shorelines and the loss of neighborhoods and towns that are no longer viable. She takes us on hikes through forests and wetlands that are already changing or have changed permanently, where scientists are documenting the adaptation of plant and animal species to changing weather and higher water.

Rush is not a scientist but a scientifically literate environmental journalist with poetry in her bones and empathy in her manner. She sits down with Isle de Jean Charles Indians in the Louisiana bayou to discuss their removal from a once robust island that has shrunk from 55 square miles to less than one square mile in the past century, a place where few can still live and many have left already. Albert Naquin talks in poignant terms about his tribe’s struggle to reassemble a homeland further inland on higher ground in the face of numerous bureaucratic obstacles at both the federal and state level. Rush allows many other actors, in places from Maine to Staten Island to Pensacola, to speak in their own voices and tell us firsthand of the wrenching experience of loss and relocation. This is not a book about those with the means to choose their homesite. This is about people who have known and adapted to one place for a long time and have no options left. The book reminds us vividly that the issue of climate change is as much about people as it is about abstract scientific concepts.

Over the years, with the hurricanes and the land loss and flooding, many people have been displaced. It got to the point that if something wasn’t done eventually there would be no Native community, no more people of the Isle de Jean Charles. Many of those that left, it looks like they’re going to be included too, and I think for them especially this relocation can do some good. The island is already a skeleton of its former self and that’s what’s happening inside the community as well. When we relocate to higher ground we will at least be able to hold on to each other. I mean if we can stay together, then we haven’t lost as much.

. . . . I mean really we are talking about having to choose to move away from our ancestral home. I know a lot of people figure we would be celebrating, to be moving to firmer ground and all. But it’s not like I threw a party when I heard about the relocation. I’ll be leaving a place that has been home to my family for right under two hundred years.

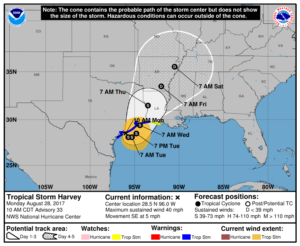

Of course, many others have experienced the pain and mixed feelings of forced relocation. Coastal storms and inland flooding have led to the buyouts and relocations of thousands of Americans in recent decades, and the toll climbs with every Hurricane Katrina, Harvey, Irma, or Maria. The toll will continue and grow.

Still, Rush’s book is not the typical call to action of a climate change activist. Rush is engaged more clearly and subtly in attempting to adjust our mindset, showing us in real terms the impacts of a history of environmental racism in which the least fortunate live in the most vulnerable neighborhoods, less by choice than because of a historic lack of options. She is raising our awareness of our historic ignorance about the ecological value of wetlands, which has caused us to compromise their protective functions and make shorelines more vulnerable. She is introducing us to the powerful sense of place of traditional communities, a sense that is generally lacking in affluent vacation homes by the sea. She is sensitizing us to a sense of doom in some communities and the lost opportunity felt by the departing residents. In short, she wants us not just to know but to feel the immediate loss produced by sea level rise today.

There are many volumes of studies and reports where one can acquire detailed scientific data about climate change. I have cited many for readers of this blog, and they are important. But it is also important to understand this crisis on its most human level. Helping us do that is Rush’s forte. Rising is a great introduction to the human cost of our global environmental neglect.

Jim Schwab