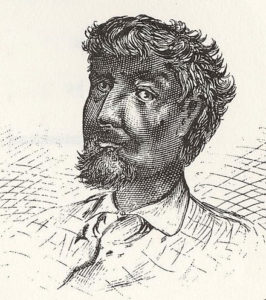

Depiction of Du Sable taken from A.T. Andreas’ book History of Chicago (1884). Reprinted from Wikipedia

Greetings from the U.S. city founded by a Haitian immigrant.

Sometime in the 1780s, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, reportedly born of a French father and an African slave mother, who had gained some education in France and made his way from New Orleans to the Midwest, settled with his Potawatomi wife on the north shore of the Chicago River. He developed what became a prosperous trading post before eventually selling it for $1,200 (no small sum in the early 1800s) before relocating to St. Charles, in what is now Missouri, where he died in 1818. According to the best-known assumption about his date of birth (1845), he would by then have been 73, a ripe age on the early American frontier. You can learn more about the admittedly sketchy details of his life here as well as through the link above. However, Chicago has long claimed him as part of its heritage, and his origins speak volumes about not only Chicago but the diversity of the American frontier despite the attempts in some quarters to continue to paint a much whiter portrait of the nation’s history than the truth affords. His story, and those of many others, can be viewed at the Du Sable Museum of African American History on Chicago’s South Side.

What does this have to do with President Donald Trump? As almost anyone not living in a cave knows by now, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL) has said that Trump, while Durbin was at the White House for a meeting with the President and several Republican members of Congress to discuss a possible compromise on legislation concerning immigration and border security, began a verbal tirade asking why the nation was allowing so many immigrants from “shithole countries” such as Africa and Haiti. Yes, Trump now denies saying it, but there were other witnesses, and even Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) acknowledges it and reports confronting Trump personally about his remarks. Moreover, the sad fact is that such remarks are consistent with a much broader pattern of similar comments ranging from his initial campaign announcement decrying Mexican “rapists” to provably untrue tweets to his infamous praise of “truly fine” people among the neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and Ku Klux Klan members protesting the pending removal of Confederate statues in downtown Charlottesville, Virginia, last summer. Since those comments last August, Trump has continued to lacerate the Twitterscape with new gems of disingenuous absurdity.

It also betrays a disturbing lack of depth of any historical knowledge that might ground Trump in the truth. There is surely little question that Haiti is one of the poorest and most environmentally beleaguered nations in the Western Hemisphere. But it helps to know how it got there, which takes us back to what was happening in Du Sable’s lifetime. Emulating the ideals of both the American and French revolutions, including the Declaration of Independence and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, deeply oppressed African slaves rebelled in 1791. An ill-advised expedition sent by Napoleon Bonaparte to suppress the revolution—Napoleon was more interested in financing his European wars with Haitian revenue than in honoring liberty among Africans—failed miserably when nearly 80 percent of 57,000 French troops first fell victim to yellow fever before being pounced upon by Haitian revolutionaries in their weakened state. Only a small contingent ever made it back to France alive. As time went on, however, Haiti found itself isolated in the New World. The United States, under presidents from Thomas Jefferson onward until the Civil War, refused to recognize the new republic, fearing a similar uprising among its own growing population of slaves in the South. Recognition finally happened in 1862, with the Confederacy in full rebellion against the Union and with Abraham Lincoln in the White House. The story gets much, much worse, including Haiti’s long-time mistreatment by France, its former colonial overseer, but those with more intellectual curiosity than our current U.S. president can read about it in a variety of books including Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution by Laurent Dubois; the fictionalized but brutally vivid and historically accurate trilogy (starting with All Souls’ Rising) by Madison Smartt Bell, whom I met 20 years ago at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference; and the more modern history of exploitation, The Uses of Haiti by Paul Farmer. There is much more; just search Amazon or your local library. It is all there for the learning. We are at least partly responsible for helping to create the historical pattern of misery and poverty in Haiti. Its people have suffered through vicious, greedy dictators like the Duvaliers and yet bravely insisted on creating a democracy despite all obstacles.

Why do I review all this? Because, especially as we celebrate the Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday and the ideals of the civil rights movement, history matters. For the President of the United States, at least a respectable knowledge of history matters, as do an open mind and a willingness to learn what matters. Little of that has been in evidence over the past year. And that remains a tragic loss for the nation.

Instead, we have a President who, before taking office, spent five years helping to peddle the canard that President Barack Obama was born in Kenya, and thus not a native-born U.S. citizen as required by the U.S. Constitution. Based on his recent comments, one might suspect that, all along, he regarded Kenya as among the “shithole countries.” It is small wonder, then, that he holds Obama’s legacy in such low regard. (Several years ago, while in Oahu, my wife and I met a Punahou School high school classmate of Obama, working as a tour guide, who said he knew Obama’s grandparents. “I was not in the delivery room,” he mused, but “I think I would have known” if Obama had not been born in Honolulu.)

The problem, as millions of Americans seem to understand, is that, despite Trump’s claim that these nations “do not send us their best,” our nation has a history of watching greatness arise from humble origins. Abraham Lincoln, in fact, arose from starker poverty in Kentucky and southern Illinois than many immigrants even from African nations have ever seen. Major League Baseball might be considerably diminished without the many Dominicans who have striven mightily to escape poverty and succeed, more than a few making it to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. (I worked in the Dominican Republic in 2000-2001, organizing HUD-funded Spanish-language training on site planning for design professionals working on reconstruction after Hurricane Georges, and can attest first-hand to the national pride Dominicans feel about their achievements in the U.S.) How many Americans visit doctors who emanated from India, Nigeria, and other countries who saw opportunity here to expand their talents and contribute to this nation’s welfare? And, lest we forget, Steve Jobs, who created more and better American jobs through Apple than Trump ever dreamed of creating, was the son of Syrian immigrants.

Only willful ignorance and prejudice can blind us to these contributions and lead us to accept the validity of Trump’s vile observations. As adjunct assistant professor, I teach a graduate-level seminar (Planning for Disaster Mitigation and Recovery) each year at the University of Iowa School of Urban and Regional Planning. Since this began in 2008, I have taught not only Americans but high-quality students—in a few cases, Fulbright scholars—from places like Zambia, Haiti, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. They do not see themselves as coming from “shithole countries,” but they do perceive that they are availing themselves of excellent educational opportunities in a nation they have typically seen as a paragon of democratic ideals. Now we are undermining that perception at a breakneck pace. These students, whose full tuition helps undergird the finances of American universities, know there are viable alternatives for a modern education in Britain, France, Germany, and Canada, but until now they have believed in the promise of America.

Meanwhile, Europeans—the very people whom Trump apparently would like to see more of among our immigrant ranks—are watching this charade with alarm and dismay. I know this evidence is anecdotal, but my wife and I, as noted in recent blog posts, traveled to Norway last July. We encountered New Zealand, South African, Danish, Dutch, Swedish, German, British, and Norwegian citizens, among others, as we traveled. Almost no one we met was impressed with Trump. This is a new development in European perception of American leadership. Moreover, our perceptions then are supported by reporting in the last few days on reaction to Trump’s comments. Despite Trump asking why we cannot have more immigrants from Norway, NBC News reports that Norwegians are largely rejecting this call as “backhanded praise.” If we want more European immigration to the U.S., we would do far better impressing them with our sophistication and our commitment to the democratic ideals we have all shared since World War II.

Beyond all this, it must be noted that thousands of dedicated Americans serve overseas in the nations Trump has insulted, wearing the uniforms of the Armed Services, staffing diplomatic missions, and representing their nation in other ways. No true patriot would thoughtlessly place them in jeopardy and make their jobs more awkward than they need to be. It is one thing to face the hostility of Islamic State or other terrorist-oriented entities because of U.S. policy. Those who enlist or take overseas jobs with the U.S. government understand those risks. It is another to engender needless fear and hostility among nations that historically have been open to American influence and leadership. How do we mend fences once they perceive the U.S. President as an unapologetic bigot?

That question leads to another, more troubling one. Silence effectively becomes complicity, but far too few Republican members of Congress have found the moral backbone to confront the reality that both their party’s and their nation’s reputation will suffer lasting damage if they remain too timid to stand up to the schoolyard bully they helped elect. A few, like Ohio Gov. John Kasich, Mitt Romney, and members of the Bush family, have demonstrated such integrity, but most have not. It is one thing to recognize that you badly misjudged the character of the man you nominated and helped elect. It is another entirely to refuse to speak up once it is obvious. Admittedly, Democrats right now have the easier job. But this problem transcends partisan boundaries. It is about America’s badly damaged license to lead in the world. We either reclaim it, or we begin the long, slow torture of forfeiting it.

Jim Schwab