Category Archives: Government

Recovering Humanity Amid Terror

When I first moved to Chicago, in November 1985, I came alone from Omaha. My wife, who grew up in Nebraska, chose to stay there until the fall semester was over. She was teaching across the river in the Council Bluffs, Iowa, public schools. I needed to settle in with my new job and find an apartment, after which we would move our belongings from Omaha. That happened in December. Jean house-sat for a carpenter friend in Omaha who vacationed in the winter until she too moved to Chicago in late January of 1986.

During those initial weeks, I stayed in a home owned by a widow in the Hyde Park neighborhood near the University of Chicago. She had a spare room to rent. We talked on a few nights as I got used to my new setting, and I learned she was Swiss but had emigrated from Czechoslovakia after World War II. She had married a Czech and was trapped with him in Prague after Hitler’s armies invaded Czechoslovakia.

In Switzerland, she presumably would have been safe. But one night, she told me, the Gestapo took her into custody because her failure to fly the Nazi flag outside their home raised suspicions. During the interrogation, they pulled out her fingernails, an absolutely excruciating torture intended to force her to reveal whatever they thought she knew about something or other, which she maintained was nothing. She simply had not flown a flag. Maybe it was a slow night for the German secret police in Prague. But the nightmare still haunted her in Chicago more than 40 years later. She seemed withdrawn and shy, telling me all this in a low but calm and insistent voice. Perhaps my willingness to listen, a trait developed as a journalist and interviewer, put her at ease about talking to me. I am not sure. It just happened.

After the war, and I don’t remember how, she found her way to the United States and was able to build a new life in Chicago. For her, this nation became a safe haven, an escape from terror.

The point of relating this brief story is that it made a huge impression on me. It made me acutely aware on a very personal level of how trauma shapes and distorts personality and lingers in the subconscious. I could not imagine reliving her experience. Just being a patient listener was deeply humbling. It is one thing to know of such horrors from a distance or from reading about them, quite another to sit across the kitchen table from a person who can share with you how she was subjected to them.

The world is still full of people experiencing such horrors even today. Certainly, the nightmare of the Russian invasion of Ukraine comes to mind, with all the trauma it will leave in its wake even if the Ukrainians succeed in defending their freedom from what clearly is now an insane regime in Moscow. There is also the war in Syria, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, Chinese oppression of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, and the list goes on. Many in America have a profound tendency to compartmentalize, to choose categories, such as white Europeans, with whom we will sympathize, and to exclude from consideration Africans and Latin Americans, for instance, even though the reality of their own suffering is often no less traumatic.

This reality has in recent days become very clear in Chicago, which Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, in his remarkably callous fashion, added to his short list of Washington, D.C., and New York, as sanctuary cities to which he would dispatch unannounced busloads of migrants from the southern border with no preparation for their arrival, in order to protest federal border policy according to his own far-right vision of who belongs in America and who does not. In response, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot has welcomed them and called for donations, but that alone will not solve the long-term problem.

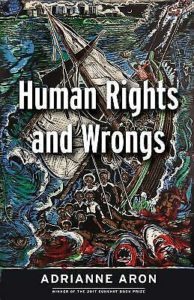

With that in mind, a small volume atop a pile of book award submissions from five years ago kept calling to me. Busy with other work, I ignored it, but it would not go away. It sat there atop this small pile on the floor, perhaps getting more attention because I had not yet decided what to do with that pile. I was not ready to cull more books from my collection. That pile was a remnant from the last year I had served as a judge for the Society of Midland Authors book awards contest. It had not made the cut, and to be honest, I had scanned it at the time. There are too many submissions, and too little time, to read every book thoroughly. Each judge uses their own techniques to manage that problem, which can involve evaluating 70 to 100 books in some categories in a matter of two or three months. My approach was to scan the first 20 pages to see if the book absolutely captivated me, then to concentrate on thoroughly reading the smaller contingent that made the cut, so that I could give potential winners the attention they deserved. With three judges on each panel, we sometimes influenced each other, suggesting attention to something that one judge found particularly meritorious. It was a collaborative effort.

None of that means the books left behind did not merit attention. They simply did not make it to the final rounds. Think of it as a preliminary heat in an athletic competition.

So it was with Human Rights and Wrongs, a 111-page collection of true stories by psychologist Adrianne Aron, who lives in Berkeley, California, and somewhat accidentally found her mission in life. She is a go-to expert for lawyers seeking to document asylum claims for immigrants who have suffered more trauma than most of us could handle. Sometimes, they can’t handle it either, but somehow, they made it to the U.S. and are seeking mercy and refuge, which is not always granted. To protect them, Aron does not use their real names, but she conveys very real stories with the flair of an aspiring fiction writer. If only what she relates were fiction. But these are real people, and she displays a unique and very human knack for finding ways to unravel the real story behind someone’s plea for asylum despite layers of fear, emotional numbness, and very often, cultural misunderstanding and language barriers.

So it was with Human Rights and Wrongs, a 111-page collection of true stories by psychologist Adrianne Aron, who lives in Berkeley, California, and somewhat accidentally found her mission in life. She is a go-to expert for lawyers seeking to document asylum claims for immigrants who have suffered more trauma than most of us could handle. Sometimes, they can’t handle it either, but somehow, they made it to the U.S. and are seeking mercy and refuge, which is not always granted. To protect them, Aron does not use their real names, but she conveys very real stories with the flair of an aspiring fiction writer. If only what she relates were fiction. But these are real people, and she displays a unique and very human knack for finding ways to unravel the real story behind someone’s plea for asylum despite layers of fear, emotional numbness, and very often, cultural misunderstanding and language barriers.

I will offer two examples. One involves a woman from El Salvador whose religious beliefs became the shield against reality that allowed her to avoid becoming detached from reality through post-traumatic stress. The other involves a Haitian man, arrested while defending himself from a drunken attacker, whose (mis)understanding of his rights in American courts was quite naturally molded by the rampantly unjust proceedings he had experienced in Haiti. Judges cannot (or should not) assume that asylum seekers see the world through the highly educated eyes of the social circles in which judges circulate. The need for a more diverse judiciary, in fact, stems in part from the frequent inability of privileged people to understand the world and experiences from which most refugees have emerged.

The Salvadoreña, whom Aron calls “Ms. Amaya,” was a simple mother from a rural community who had a story to tell, but her lawyers feared that, if she told it all, she would not be credible. Yet, not allowing her to tell her whole story would deprive her of the power to tell her own story as she knew it. It would continue the process of disempowering her that had begun in Central America when soldiers came to her house, accusing her of hiding arms of which she knew mothing. The soldiers took her to an army post, where she was gang-raped and tortured for four days before being released. She prayed to the Virgin Mary for salvation for her children’s sake and thanked her when it was over and she was still alive. As the detention wore on with other ordeals, she saw the hand of God in causing soldiers’ lit matches to go out when they threatened to set her on fire, and when their rifles misfired as she expected to be shot. But how could she know this was an intimidation tactic common in Latin America? It fell to Aron, the psychologist, to document the use of such tactics and to show that Ms. Amaya’s deep faith in divine intervention and mercy in fact protected her from the sort of deep psychological damage she might otherwise have suffered from confronting the reality of what was done to her. Religion gave her a belief structure that fit with her culture and afforded her some sense of divine protection.

Having helped make a successful case for Ms. Amaya’s grant of asylum, Aron also thought it wise not to mention in her brief that some of the oppressive tactics used by the Salvadoran military were actually consistent with those taught to visiting Latin American military officers by the U.S. School of the Americas. Challenging the judge’s world view might not have led to the best results for her client. Save that education for another day.

Louis Antoine was attacked by a drunk one day who stumbled into his path on the way out of a bar. As local police arrived, they saw him striking back. He ended up in the police car; the drunk walked away. Louis peed his pants from fear on the way to the station. After growing up in Haiti, being beaten by the Tonton Macoutes, the murderous gangsters who enforced the rule of dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier when he was a child and who had killed both his mother and father, he expected nothing but the worst when hustled into the back of a police car. One obstacle to retaining the political asylum granted him earlier was that he did not understand what he had pled to in court and, speaking Haitian Kreyol, did not understand the proceedings. Nor did he understand that the purpose of the French translator sitting with him was to help represent him because he spoke only Kreyol, not French. Why had he not asked for translation into a language he understood? It was not his experience that the defendant was allowed to understand. In Haiti, the French-speaking elite simply handed down decisions to the less fortunate masses. Simply put, he was unaware of rights in America that he had never experienced in Haiti. The psychologist’s job was to explain all this, based on the horrific injustices that Louis Antoine had experienced in Haiti. The man had shown the resourcefulness to save money and find his way to the United States, seeking a better life, so it was not emotional inhibition or trauma that held him back, but lack of knowledge of how the system worked. It fell to Aron to document his history and make clear where the American system had failed him until she helped reframe his case.

Underlying these and several other poignant stories is the fact that Aron’s techniques were not simply a matter of professional expertise, but of her very human willingness to listen, to find effective interpreters, and to probe deeply enough to make sense of it all and restore voice and agency to people who had mostly experienced distance and disempowerment from those who determined their fate. The American system has the potential to dispense real justice, but only when staffed and supported by people willing to invest the time and moral imagination to make it work.

For that very reason, although the book is now five years old, every story it tells retains a powerful relevance to current circumstances. We remain a nation that must rise above its petty prejudices to bestow mercy and live up to the very promises that brought Aron’s clients here in the first place.

Jim Schwab

Do We Need a Gun Victims Memorial Day?

I am going to keep this short and simple for two reasons. One, I am writing on the morning of Memorial Day, and I want to celebrate the holiday and spend time with my family. Our grandson Angel, who is graduating from high school on June 6, and from a Chicago Police and Fire Training Academy program on June 1, is coming with his father to earn $20 from me for assembling the brand-new outdoor grill I bought Saturday at Menard’s, and we will plan his graduation party. So, there is all that. Two, the coverage of the mass murder of school children at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, has received nearly wall-to-wall coverage in the news media, so it’s not clear I need to add to all that, other than to note that the tragedy of gun violence was perpetuated just yesterday by some shooting in downtown Chattanooga, Tennessee, that wounded six teenagers and sent yet more police officers into a scramble to sort out who did what and to rescue the victims. Gun violence comes in various forms, not just mass murders, but one wonders when it will end and what it will take to wake up the most stubborn defenders of indefensible views of Second Amendment rights. Those rights are real, within limits, as all rights are, but they do not and should not tower above all other rights in a civilized society. If, that is, we are willing to consider the United States of America in 2022 civilized.

It is all getting old, very old. Consider the lineup of just some of the major incidents with mass murders in the past decade:

- Sandy Hook Elementary, Newtown, Connecticut—27 dead, 2 injured

- Aurora Theater Shooting, Aurora, Colorado—12 dead, 70 injured

- Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.—12 dead, 8 injured

- San Bernardino Mass Shooting, San Bernardino, California—14 dead, 21 injured

- Orlando Night Club Massacre, Orlando, Florida—49 dead, 53 injured

- Las Vegas Strip Massacre, Las Vegas, Nevada—58 dead, 546 injured

- Texas First Baptist Church Massacre, Sutherland Springs, Texas—26 dead, 20 injured

- Santa Fe High School Shooting, Santa Fe, New Mexico—10 dead, 13 injured

- Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—11 dead, 6 injured

- Thousand Oaks Nightclub Shooting, Thousand Oaks, California—12 dead, 22 injured

- Virginia Beach Municipal Building Shooting, Virginia Beach, Virginia—12 dead, 4 injured

- El Paso Walmart Shooting, El Paso, Texas—22 dead, 26 injured

- Boulder Supermarket Shooting, Boulder, Colorado—10 dead

- Buffalo Supermarket Shooting, Buffalo, New York—10 dead, 3 injured

- Robb Elementary School Massacre, Uvalde, Texas—21 dead, 17 injured

The Mother Jones site from which I pulled the above data lists 129 such events dating back to 1982 with three or more fatalities, of which I used only those since 2012 where the dead numbered in double digits. Although Mother Jones does not offer an overall tally, the numbers climb well into the hundreds of dead and hundreds of injured, and well, at some point, what’s the point of counting. There may well be more next week. There were only ten days between the most recent incidents in Buffalo and Uvalde, Texas, which alone produced 31 deaths and 20 injuries. It is a terrifying tally.

America’s problem, moreover, is not limited to mass shootings, which unquestionably produce the most news coverage. But gang shootings in cities big and small (yes, including but hardly unique to Chicago), domestic violence, suicides, arguments in bars, and heaven knows how many other circumstances involving people with firearms produced, according to the Pew Research Center, more than 45,000 deaths from gun violence in 2020, the most recent year for which complete data have been compiled. Add that up over a decade, and we have numbers that rival the sacrifices of American military heroes in the largest and most violent wars this nation has ever fought, including both World War II and the Civil War.

That leads me to a modest proposal, probably one that is well ahead of its time, but the fight for a holiday to honor the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., took three decades to become a reality. On Memorial Day, however controversial my suggestion may be, and I expect some pushback, I must wonder if the time has come to begin to consider a Gun Victims Memorial Day. Someday, if we are in fact the civilized nation we imagine ourselves to be, we will look back in amazement that we tolerated all this for so long, listened to inane arguments against even the most basic proposals for gun control, such as banning assault weapons or at least raising the age requirements for purchasing such weapons, or instituting universal background checks, and wonder, as other nations do, as we still do regarding racial equality and civil rights, why we ever had to fight so hard for something so sane and so simple. And a Gun Victims Memorial Day would help us to tell each other at that time in our future, “Never again.”

It does not matter what day we choose. Gun violence happens every day in America. The dates of various mass murders pile up almost weekly now. The National Rifle Association, governors and senators and other public officials enslaved to the NRA, all repeat the same tired assertion that guns don’t kill people, people kill people, as if just anyone with a butcher knife could rain down terror on a school or a concert in mere minutes, as if . . . . well, one could go on, but as I say, what is the point of repeating the obvious? Let’s get to work removing the obstacles to justice from public office. That is the first step toward honoring the memory of so many who have died so unnecessarily, so gruesomely.

Jim Schwab

Modern Links to Lincoln

It was spring break in the Chicago Public Schools this past week (April 11-15). Despite busy lives, I thought my wife and I should do something special with Alex, our 13-year-old grandson, so I proposed a visit to Springfield, the Illinois capital, to visit the Abraham Lincoln Museum, which we had never seen. The museum is part of a complex, opened in 2005, that includes the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, an invaluable resource for students and scholars on about Lincoln, the Civil War, and related historical topics, and the Illinois State Historical Library, founded in 1889. Across the street sits Springfield Union Station, which now contains an exhibit about the 2012 Steven Spielberg movie titled Lincoln. The library and museum are connected by a walkway above the street.

From Chicago, Springfield is a fairly easy day trip, about three to three and a half hours each way, depending on traffic. The Lincoln Museum and the State Capitol are popular field trip destinations for Illinois schools, particularly those in central Illinois. Even with many schools out on the day we came, the museum was an obvious magnet for smaller groups of teens and for families. Lincoln, despite nearly 160 years’ distance in time from us today, remains one of the most fascinating figures in U.S. presidential history. The museum notes that only Jesus Christ may be the subject of more biographies than Lincoln himself. It is interesting to contemplate that both had more obscure beginnings than most major historical figures. Does that add to the fascination? I suspect that may well be the case.

Others have written about the museum and library since it opened, but this is a unique time to visit, given contemporary events in Ukraine, where war is ravaging an entire nation much as it did our own in the 1860s. One is almost compelled to make comparisons, and guests were asked to use flower-shaped paper cutouts and glue to write messages on blue and yellow strips that will be displayed to communicate messages of support to the Ukrainian people in their struggle for freedom against a Russian invasion. Blue and yellow, of course, are the colors of the Ukrainian flag. Jean and Alex both wrote their own messages; I wrote mine in Russian, which I learned half a century ago at Cleveland State University in classes half filled with Ukrainian American students. Мир, I wrote on half of the petals I glued together; Свобода, I wrote on the overlying petals: “Peace” and “Freedom.” Unfortunately, I do not know any Ukrainian, but most Ukrainians know Russian. The message is clear enough.

But back to Lincoln and his own times, when a battle raged for the unity of the nation in the face of slave holders determined to maintain white supremacy at any cost in a war that soon enough led to the liberation of more than four million enslaved African Americans. Nothing is ever simple, and Lincoln was not perfect, but his saving grace, unlike a recent American president, is that he never thought he was. He was simply an elected leader who was determined to find a path for his nation through its darkest days, and somehow succeeded. But he was also assassinated by John Wilkes Booth before he could ever see some of his most important gains for equality sacrificed to political myopia and expedience with no opportunity to do anything about it. His own vice-president, Andrew Johnson, proved not only inadequate to the task but riddled with racial bias. Vice-presidents in those days were often mere ticket balancers with little thought given to their abilities to lead the nation. Sometimes, one wonders how much has changed in that respect.

The intriguing thing about the museum is the way in which its designers have chosen to convey to visitors the realities of Lincoln’s life and times. This is truly a modern museum. After taking advantage of the opportunity to “get a picture with the Lincolns,” standing among their images in the lobby, we attended a short holographic presentation called “Ghosts of the Library,” in which a young researcher named Thomas helps people envision how the thousands of documents and historical items in the facility can come to life and share their stories. We realize that every item in the collection has its own story, so many that one could spend a lifetime hearing them all, but, of course, we had only a few hours to get the gist.

The intriguing thing about the museum is the way in which its designers have chosen to convey to visitors the realities of Lincoln’s life and times. This is truly a modern museum. After taking advantage of the opportunity to “get a picture with the Lincolns,” standing among their images in the lobby, we attended a short holographic presentation called “Ghosts of the Library,” in which a young researcher named Thomas helps people envision how the thousands of documents and historical items in the facility can come to life and share their stories. We realize that every item in the collection has its own story, so many that one could spend a lifetime hearing them all, but, of course, we had only a few hours to get the gist.

But that gist then, for us, moved to another theater, in which another narrator walked us through Lincoln’s life from a deprived childhood in a wilderness cabin to the peaks of power in the White House, surrounded by turmoil and controversy, until a gunshot rings out, and we know that Booth has struck at Ford’s Theater, and Lincoln at that point, as Secretary of War Edwin Stanton famously stated, “belongs to the ages.”

Paralleling that sequence are two very different displays, one small, approximating the size of the cabin in which Lincoln grew up, showing him reclined before the light of a fireplace, book in hand, educating himself, for he had only two years of formal education in his entire life. But his absolute fascination with books, and his ambition, served him well. In those days, one became a lawyer through such self-study under the aegis of a practicing lawyer, and it gradually became clear that Lincoln was an intellectual match for most of those around him. He served in the Illinois legislature in the 1830s, in Congress during the Mexican War, and despite periodic defeats including two Senate races, finally won election as president of the United States.

For Alex, seeing the cabin in which Lincoln grew up seemed to make an impression. Although Alex’s life had its challenges before we were awarded custody, he now lives in our three-story brick home with three bedrooms and modern furnishings. Yet, here was Lincoln, teaching himself to read and ultimately making one of the most profound impacts on human history. As I said, perhaps that is what makes the story so compelling.

Across the hall was a replica of parts of the White House and a sometimes-noisy presentation of the Civil War years, with holographic figures in one part of the passageway speaking aloud what was often said in print, in letters, newspapers, and other forums of the time. Some are angry men denouncing him as incompetent, but another is a young woman writing to the president about her brother, serving in the Army, who, in her view, did not need to serve alongside “Negroes” who would be unlikely to fight. The comment is even more compelling in light of our historical knowledge that Black troops, who joined the Union army in the second half of the war, were among the bravest, perhaps in part driven by the emerging news that Confederate forces who captured Black soldiers simply executed them instead of placing them in prisoner camps, although plenty of white troops died under inhumane conditions in such camps before the war ended. What comes across most clearly from this mode of presentation, in a way that written words cannot convey so well, is the sheer nasty divisiveness that infested the country in Lincoln’s time. It makes me wonder what impression this makes on anyone who still approves of the January 6 insurrection at the nation’s capital, inspired by a president who refused to acknowledge loss. When one thinks about Lincoln’s losses on the way to the White House, and the high cost of political division during his presidency, the lack of political grace by some today is even more appalling.

All of that is already compelling enough for a museum visit, but the museum offers one more powerful witness by including what docents warn is a display that visitors may find deeply disturbing. This new exhibit, “Stories of Survival,” opened at the Lincoln Museum on March 22 but was developed by the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center. It displays artifacts and photos from the Holocaust in World War II, but also more recent events such as the migrations of refugees from Middle East hot spots such as Syria. The stories and images are heart-wrenching. In my mind, they force two compelling questions: What is different today from the slaughter of the Civil War, and how does that contrast with events in Ukraine?

The biggest single factor, it seems to me, is that those who were resisting the Union in 1861, and who started the war, as Lincoln anticipated, by shelling Fort Sumter in South Carolina, were doing so not to advance human freedom but to preserve the domination of one race over another. In Ukraine, a sovereign nation, Ukraine, although an offshoot of the politically depleted former Soviet Union, is seeking to preserve its gains in building democracy and freedom. It is the commitment to its own independence and the attraction of a more dignified and promising political system that drives the impressive Ukrainian commitment to fight so well against the odds. The outcome remains in limbo, the destruction remains appalling, but the desire for a free and better life could not be clearer. In other cases, such as Syria (which has been aided by Russia), the power of an oppressive system remains the driving force in continuing genocidal warfare now into the third decade of a twenty-first century that we might have hoped would bring an end to such conflicts. Instead, we find ourselves confronted with evidence of a continued determination by strongmen throughout the world to enforce their will and of the ability of all too many to follow such leaders and excuse their behavior.

It is a sobering realization that the struggle for human freedom, dignity, and equality remains the compelling work of our time.

On the way home, I asked Alex what he felt he had learned from his visit to the Lincoln museum. Sitting in the back seat of the car, he thought for a moment and then said, “Being president is a very difficult job, and lots of people will be against you or criticize you.”

If he got that much out of it at his age, I thought, this trip was well worth the time. I did not ask about the “Stories of Survival” exhibit. It’s a bit much for the most mature adults to take in, let alone a seventh grader.

Jim Schwab

No Time for Cowards

This past Sunday, I attended a rally for Ukraine at Chicago’s downtown Daley Plaza. I am no expert at crowd counts, but it was clear that hundreds attended, filling most of the plaza. The point was painfully obvious: People were hugely upset with the unwarranted Russian invasion of Ukraine that began two weeks ago.

It is hard not to notice such things in Chicago, particularly on the near North Side. We live about one mile from a neighborhood known as Ukrainian Village. Chicago hosts the second-largest Ukrainian population in the U.S., estimated at 54,000. Many of us know or work with Ukrainian-American friends and colleagues. One of our daughters has a long-time friend from her junior college years. She talked to her recently and reported that, while Ivanka had talked to her frightened grandmother in Ukraine, she subsequently learned that her grandmother died in a Russian attack on her apartment building.

Welcome to Hell on Earth, Putin-style. Nothing is too brutal or inhumane if his personal power is at stake. Despite this savage reputation, well-earned in places like Syria, he has his admirers in the U.S., including a recent former president who shares an inability to put morality ahead of self-interest. Trump’s willingness to sacrifice Ukraine for the mere bauble of finding supposed dirt on Joe Biden surely provided a signal to Putin that Ukraine was fair game. The infamous telephone call between Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zalenskyy, of course, led to Trump’s impeachment, followed by a highly partisan acquittal in the U.S. Senate. Both Trump and Putin have massive amounts of blood on their hands. With more than 2 million Ukrainian refugees so far flowing into Eastern Europe, this is no time to be polite in saying so.

My own awareness of the crisis is heightened by having been a political science major at Cleveland State University, where I indulged in Soviet and Russian history and learned a modest dose of the Russian language in a class half full of Ukrainian-Americans. That enabled me to read some of the signs at the rally that were not in English, though most were. One caught my eye: Русскийй Военный Кораблъ: Иди Нахуй. It was the challenging anatomical assignment that a Ukrainian commander on Snake Island threw back at a Russian warship that demanded his troops’ surrender. It seemed to sum up the sentiment on the Ukrainian side of the conflict.

My own awareness of the crisis is heightened by having been a political science major at Cleveland State University, where I indulged in Soviet and Russian history and learned a modest dose of the Russian language in a class half full of Ukrainian-Americans. That enabled me to read some of the signs at the rally that were not in English, though most were. One caught my eye: Русскийй Военный Кораблъ: Иди Нахуй. It was the challenging anatomical assignment that a Ukrainian commander on Snake Island threw back at a Russian warship that demanded his troops’ surrender. It seemed to sum up the sentiment on the Ukrainian side of the conflict.

Why was I there? Along with having donated $100 that Trip Advisor offered to match to support the efforts of World Central Kitchen to feed the mass of refugees at the Polish border, I felt it was the least I could do in a nation of comforts while millions of Ukrainians were being forced either to flee their homes or fight for them against a massive invading Russian army. That army has been finding, to Putin’s surprise, that Ukrainians are not inclined to surrender their sovereignty, especially in the face of massive human rights violations and war crimes. What awaits them if they surrender may be worse than the fight itself, so they will fight.

The issue is that, after reaching seemingly comfortable accommodations in recent decades with autocratic and authoritarian regimes in major nations like Russia and China, we collectively underestimated the potential malevolence of such leadership anywhere. It is certainly true that the United States alone, and even NATO and the European Union collectively, cannot hope to convert every nation in the world to democratic principles. Those are societal features that must be internalized by any culture that wishes to share a more enlightened world view. Whole books, particularly but not only by political scientists, have explored the necessary conditions for fostering such systems. In the past decade, even in the U.S., we have seen just how fragile democratic systems can be when faced with an onslaught of disinformation and the personality cults of those who offer simplistic answers to complex questions.

But the problem for Ukraine is different. Ukrainians had been steadily and deliberately working to steer their own society toward those principles, and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy represents a remarkable commitment by new and talented leadership to those ideals. The problem is that Ukraine is a former Soviet republic with an extensive Russian border, led by a neighboring leader who suffers from profound paranoia and a delusional belief in the glory of the former USSR. Putin is remarkably lacking in moral principle and empathy, and thus, it should be no surprise that, at the same time that he refers to Russians and Ukrainians as ethnic “brothers”, he is willing to kill his alleged brother in order to save him from Western-style democracy. It is the classic bear hug of an abusive older sibling whose only real concern is getting what he wants, no matter the cost in human lives and suffering. If they don’t love me, the thinking goes, I will make them wish that they did.

The concept of doing the hard work required to create a Russian society that is actually attractive to the outside world escapes him. After all, he does not even trust his own people with the truth. If he did, the Russian Duma would not have rubber-stamped legislation to impose 15-year prison sentences on those who tell the Russian people anything the Kremlin does not want them to hear—such as the simple fact that Russia has launched an unfathomably violent attack on a peaceful neighbor.

The challenge for America and the democracies of the world is to rise to the occasion and accept whatever sacrifice may be necessary to squeeze the Russian war machine dry of whatever resources it needs to maintain its grip on Ukraine, which could easily be followed with a bear hug of Moldova and other former Soviet republics and allies, possibly including some that have already joined NATO. That, of course, could trigger the insanity of world war. It is certainly the case that direct military confrontation between NATO and Russia may be highly inadvisable at the moment, given Russia’s nuclear arsenal and the possibility of increased irrationality by Putin if he senses that he is a trapped man. The stakes for the world in such a case are extremely high.

There are, nonetheless, numerous ways in which we can help and indeed already have helped, including provision of military weapons like anti-tank missiles and other vital supplies.

The sudden withdrawal from Russia of major Western companies can also send a signal to Russian citizens, otherwise deprived of legitimate information, that the world is unwilling to tolerate Russian aggression. At the rally, for instance, one speaker noted that McDonald’s was still doing business in Russia. That is no longer true. Dozens of major U.S. corporations, including McDonald’s, are suspending business in Russia, although McDonald’s is paying its workers while the stores are closed. That move may be more powerful than simply withdrawing completely, by causing numerous workers to wonder about the logic of an American company paying them to stay home. Even AECOM, a major infrastructure and engineering consulting firm with which I have had some experience, has chosen to suspend operations in Russia. Eventually, Russia will have a difficult time replacing such expertise.

The sudden withdrawal from Russia of major Western companies can also send a signal to Russian citizens, otherwise deprived of legitimate information, that the world is unwilling to tolerate Russian aggression. At the rally, for instance, one speaker noted that McDonald’s was still doing business in Russia. That is no longer true. Dozens of major U.S. corporations, including McDonald’s, are suspending business in Russia, although McDonald’s is paying its workers while the stores are closed. That move may be more powerful than simply withdrawing completely, by causing numerous workers to wonder about the logic of an American company paying them to stay home. Even AECOM, a major infrastructure and engineering consulting firm with which I have had some experience, has chosen to suspend operations in Russia. Eventually, Russia will have a difficult time replacing such expertise.

No discomfort for America and even most of Europe, however, can even begin to approach that of the struggling, fighting Ukrainians in this moment. The last time the United States saw large numbers of war refugees wandering its own landscape was during the Civil War. Even the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, killed nearly 3,000 citizens in places of commerce or government, but those who fled returned to homes physically untouched by conflict. If we muster the will, we are capable of far more support for Ukraine in the present situation than most of us imagine. Are gasoline prices higher as a result of banning imports of Russian oil? Let’s find a way to handle it without turning it into a partisan cudgel over inflation. In the longer run, we can only benefit from expanding our commitment to electric vehicles, renewable energy sources, and other ways of escaping the nagging noose of fossil fuels. A world that needs fewer and fewer resources from corrupt petro-states is a world that already is better prepared for peace.

It is one thing to expand world trade as an avenue toward peace. It is another to be fatally dependent on fundamental commodities that put us in the death grip of authoritarian states. We have the means, the wisdom, the diversity, and the creativity to find our way out of that death grip. Let’s get busy, stop bickering, and commit ourselves to a more democratic and less violent world.

Jim Schwab

FOBOTS

Over the past weekend, two legendary quarterbacks who may be outlasting their time in the spotlight went down to defeat with their teams. Neither Aaron Rodgers, of the Green Bay Packers, nor Tom Brady, recently with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, will be headed to the Super Bowl. At their current salary level and respective ages, there is also the question of whether they can find a National Football League team that wants to spend what is necessary to keep them on the field. If not, retirement may be involuntary for either or both.

Rodgers earned some well-deserved opprobrium when he dishonestly claimed to have been vaccinated, even though he was not, putting his team and others at risk because of his own arrogance. The NFL probably buttressed that arrogance with a modest penalty that was largely a slap on the wrist for a man with an eight-figure income. He has enjoyed a secondary stage hawking State Farm insurance, but for superstars, such ads are merely an auxiliary revenue stream. They can, however, last a lifetime. Just ask Joe Namath. For some, there is a new career in sports announcing, a legitimate second career for people like John Madden. Such alternatives require a different set of talents from sports itself, so not everyone can make the transition. Honorably, some athletes have used their celebrity power to advance charitable causes and social justice; LeBron James comes to mind. Endorsements, of course, require little more than lending one’s name to a product or project, a process commonly known as branding. But that does not always put one in the limelight, at least not directly.

That is the question I wish to raise here because the desire for attention is a matter of personal psychology. There is nothing inherently wrong with continuing in a position as long as one is capable. However, there are issues involving personal maturity and perspective that are worth exploring. For example, does your reluctance to step away from the limelight betray the lack of any larger focus in life than simply being the center of attention, or do you have a larger sense of purpose? Conversely, is your determination to remain on stage a function of narcissism or an oversized ego?

Merriam-Webster states that the earliest known use of the acronym FOMO—fear of missing out—dates to 2004. Merriam-Webster defines FOMO as “fear of missing out: fear of not being included in something.” Because I jokingly refer to myself as a “compulsive extrovert,” I can relate somewhat to the idea, which long ago went viral, but emotional and professional maturity must at some point prevail. One cannot be everywhere, and priorities are essential. We can all stop and ask ourselves why something matters. In many if not most cases, we must also ask whether it matters.

I propose that we apply the same logic to what I will now label FOBOTS: the fear of being off the stage. As Merriam-Webster’s definition states, FOMO simply relates to a desire to be included. FOBOTS is about being the center of attention. Much more ego is involved. The maturity equation here is different and far larger. The question is whether the person in the limelight is hogging (or hugging) it because of a deep need to feel important, or has some larger purpose for which he or she is uniquely suited. In the latter category, I would suggest that, while Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was frequently in the limelight, it was not often complimentary in his day, he suffered a good deal of withering criticism for taking principled positions on hugely significant issues of human rights, and he was clearly more interested in moving the agenda on civil rights than in self-glorification. He also left behind a very strong bench of independent thinkers in the civil rights movement who have continued to carry the banner long after he was assassinated. Moreover, he was still very young (39) and capable when the assassination occurred. He knew it was a possibility because of the racial hatred and violence that still exists in the United States of America, but there is no evidence that it is the outcome he wanted. No one with his skills and vision wants to be murdered. Such people do want the satisfaction of moving the moral arc of the universe, to use the biblical metaphor. To care about that, they must care about others.

So, who really suffers from FOBOTS? Certainly, plenty of politicians. The sickness today is clearly rampant because the former president, refusing to concede loss in the 2020 election despite an absolute dearth of evidence of voter fraud, cannot abide departing the stage, even when he is harming the prospects of his own Republican party by supporting primary candidates whose agenda is to help Trump exact revenge on his perceived enemies and those who refused to participate in his scheme to overturn the election. In contrast, former President George W. Bush, having served his two terms, virtually disappeared from the public stage and launched a new avocation as a portrait painter. His father, President George H.W. Bush, willingly departed the White House to allow a peaceful transfer of power to President Bill Clinton. And most notably, President Jimmy Carter, who lost re-election to Ronald Reagan, has used his post-presidency to advance a variety of humanitarian causes in a dignified manner consistent with his own Christian principles.

With Trump, however, we have the spectacle of a defeated president who refuses to concede and refuses to honor the results, and simply manufactures false accusations by the wagon load to justify his position. What is best for the country matters little; it is the loss of the limelight, the fear of being off the stage, that dominates his psyche, which was shaped by early successes in life in being able to garner public and media attention as a glamorous son-of-wealth businessman and reality television star. Sorry, Trump followers, there is nothing more there. This is not about your welfare or any agenda that benefits anyone other than Trump himself. It never has been.

If the damage were limited, however, to a continued presence of Trump in the political quarrels of the day, that would be one thing. But the sickness runs deep enough, and the mass paranoia wide enough, to allow him to intimidate hundreds of other Republican politicians who also suffer FOBOTS. The fear of being primaried by a Trump wannabe is so pervasive that almost an entire generation of Republican leadership has lost its moral stature to the point of fearing losing their own smaller stages—as Senators, U.S. Representatives, governors, and now even as Secretary of State in swing states. Only a handful of Republican leaders, notably including Reps. Liz Cheney of Wyoming and Adam Kinzinger of Illinois—are willing to defy him and seek to build the badly needed new leadership that can guide the Republican party out of its moral wilderness. Notably, Kinzinger, while choosing not to run again this year, is launching a new organization to fight what he considers right-wing extremism in the Republican party.

The underlying question of FOBOTS is the emotional intelligence and maturity it takes to realize when it is time to make room for others who can follow in your wake. This requires having had some sense of a larger professional and moral purpose in life. To avoid FOBOTS, it is necessary to think through, in both moral and practical terms, what legacy you wish to leave behind. For many people around the world, that vision is focused on family, on creating opportunities for children, modest goals that do not require oversized egos, and those people should be admired. For the rare few, at various levels of public attention, the public stage is an opportunity to advance a good cause, to elevate humanity, to make life better for others who follow. FOBOTS is an indicator of narcissistic personality disorder.

There is nothing wrong with being in the public spotlight. I have occasionally enjoyed being there myself. But the question always remains: Why are you there, and what larger positive purpose will your presence serve? If you cannot answer that question with honesty and integrity, it may be time to find the exit. Use your time in the shadows to search your soul.

Jim Schwab

Truth and Consequences and January 6

Like most people, I learned of the insurrection that resulted in five deaths and considerably more than 100 injuries to Capitol police from television news. Don’t ask me which channel; it was probably either CNN or MSNBC, but honestly, I don’t remember. I only remember what I saw—the searing image of American citizens attacking the seat of their own government on behalf of a President who lied to them because his twisted psyche did not allow him to admit that he had lost an election, fair and square. If he believes that the election was stolen, it is not because he has ever had any evidence to that effect. It is because he has repeated the lie to himself so often that he has internalized it completely. Such men are very dangerous.

There are plenty of good, well-written commentaries on the events of January 6, and it is not my aim to add another broad assessment of the day. The testimony before, and the final report of, the House Select Committee will add immensely to our knowledge, but it remains to be seen whether it can change minds. Even in 1974, as Richard Nixon was about to resign the presidency after a visit by a delegation of distinguished Republican Senators convinced him the gig was up, about one-quarter of the American public still sided with him, either disregarding or disbelieving the criminality on display from the Watergate affair. Even the most venal and corrupt politicians have always had their supporters, often until the bitter end. It is not as if the larger public is composed entirely of angels, after all. When the support fades, it is usually because the politician in question is no longer useful.

Corrupt and authoritarian politicians are almost always bullies who are highly skilled at making offers that their followers, and often others, cannot refuse. There is nothing new about this phenomenon. It is as old as civilization itself. The Bible is replete with evidence of such venality, dating back thousands of years.

So, what do I have to offer?

On the afternoon of the insurrection, I was preparing for a pair of sequential consulting meetings when the news caught my attention. That led to a mercifully brief text exchange with someone I will leave unidentified. I will paraphrase for clarity while sharing its essence. The point is not who it is, but his perceptions in the face of what effectively was a coup attempt. I understood his politics for many years beforehand; sometimes, he would needle me about it, and sometimes in recent years I was forced to terminate a conversation that, in my view, had departed earth’s orbit and no longer made sense.

But at that moment, I had to believe even this riot, insurrection, coup attempt, call if what you will, would be too much even for him. I was wrong.

I asked if he was still happy with Trump after Trump had incited an insurrection at the Capitol.

I was told that, after years of corruption that no one had challenged, except for Trump in the previous four years, “people are fed up.”

I want to step back here and make two points about this expression of frustration.

First, regarding corruption, this is a vague term that, without specifics, can be used as a broad brush against almost anything one disagrees with, and I believe that was happening here. There is, in my view, little question that corruption has at times affected both political parties. Personally, I have been perfectly willing to cross party lines to vote against candidates and office holders with documented records of corruption of any kind. I intensely dislike politicians who put self-interest ahead of the public interest. I am also aware that my disagreement with their policies does not constitute evidence of their corruption. Those are two different things, and we need to respect that difference if democracy is going to involve any kind of principled debate about what is best for our society. There are times when those lines are blurred, and times when it is clear. For instance, I was pleased last year when Democrats in the Illinois House of Representatives voted to replace long-time Speaker Michael Madigan, who had become entangled in a corruption scandal involving Commonwealth Edison Co. and its parent Exelon, with Chris Welch, who became the first Black Speaker in Illinois history. Welch may not be perfect either, but it was time for Madigan to leave. He has retired into obscurity, but he may yet face federal charges. I could name dozens of such situations in either party.

But to suggest that no one had addressed such corruption until Trump did so is ludicrous. It also demonstrates a willful blindness to facts. The litany of evidence of Trump’s shady transactions in both business and politics is overwhelming, from the $25 million fraud settlement in the lawsuit against Trump University, to the tax and insurance fraud charges now being brought against the Trump Organization by the Manhattan District Attorney, to the investigation of Trump’s demand of Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find” enough votes to allow Trump to claim victory in that state in the 2020 election—the details have filled multiple books over many years. No matter the depth of evidence that Trump not only does not fight corruption, but personifies it, followers will insist on dismissing such evidence, almost surely without ever reviewing it. Nonetheless, it is absolutely clear to anyone reading all this, as I have, that Trump has never been the weapon against this corruption that this complaint suggests.

For those who may think otherwise, or want to better arm themselves to discuss this topic, I include a short, incomplete bibliography of Trump-related investigative literature at the end of this blog post. Beware: It may keep you occupied for weeks.

But there is also the claim that “people are fed up.” This deserves closer analysis. One could ask, Fed up with what, exactly? My correspondent cited Biden “bringing back old retreads that Obama had in his cabinet.” That is hardly a crime, of course, and may well have indicated a preference by a new president facing a crisis of confidence in government for choosing experienced people who know how to make government work. That is hardly cause for a riot, let alone a coup attempt, and I said as much, though admittedly I may have sparked further anger in referring to the corruption claims as a “bullshit excuse” for an insurrection—especially since the express purpose was to prevent certification of the election. He also noted the need for better trade agreements, for someone to “actually help the working person,” and the loss of manufacturing jobs. I would readily agree that these are all legitimate political issues, subject to debate both on the streets and in the media, and in Congress and state legislatures, but justification for an insurrection?

That was the red line I could not cross, nor could I accept that anyone else should be allowed to do so.

The idea that all this frustration, not all of it based on accurate perceptions, justified an attempt to overthrow an election underlines a sense of civic privilege that I find appalling. If your preferred candidate failed to make his case to the American people—and that is precisely what happened to Trump—it does not follow that the only path forward is insurrection. The presumption behind this logic is deeply rooted in white privilege, even if its advocates do not wish to consciously own that brutal truth.

After all, if anyone is entitled to a sense that they are pushing back against persistent injustice, it would be African Americans, who can cite centuries of brutal suppression and slavery prior to the Civil War, the use of home-grown terrorism through organizations like the Ku Klux Klan to suppress Black voting rights and citizenship and economic opportunity, Jim Crow laws that enforced inequality well into the 20th century, vicious housing discrimination, and violent police actions, such as those of the Alabama state troopers who assaulted peaceful demonstrators in Selma in 1965, all of which make pro-Trump protesters’ allegations of unfairness pale in comparison. Yet, most African American citizens have persisted across centuries to use what levers they have within the democratic system to achieve a more equitable society. Admittedly, there are times when tensions have boiled over, but who could reasonably have expected otherwise? I am not justifying violence, but asking reasonable people to consider the disappointments to which Black Americans have been subjected for generations before making comparisons to the complaints of the MAGA crowd.

Moreover, such issues of delayed justice have affected other minorities, such as Chinese, the subject of an immigration exclusion law for decades, the Japanese internment during World War II, and widespread prejudice and discrimination against Latino immigrants over the past century. One could go on, but the point is clear. All have sought doggedly to work through the existing system to resolve injustice.

That leads to the next element of the exchange, in which I insisted that any Democrat instigating such an attack would be accused of treason, and that to react otherwise to Trump’s insurrection is “blatant hypocrisy.” I wanted to draw direct attention to the double standard that was being applied by many Republicans in this instance. In fact, I added, “Coup attempt is crime.” Democrats made similar allegations, of course, in the second impeachment trial.

That led to the countercharge that Democrats were hypocritical in allowing “looting, burning, shooting and harassing of innocent people” in the demonstrations and riots that followed the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in the summer of 2020. He then referred to Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot as “part of the elitist liberal problem in this country.” As with the corruption issue, we were back to the broad-brush approach to asserting problems without specifics.

At that point, I decided to end the conversation because it seemed clear that the discussion was going to veer off track. I made clear that “I have never endorsed violence and I never will.” But I added that in Trump’s case, “This is an official condoning this,” which separated it from mayors who did not like the violence in their cities, but were faced with challenges in deciding the best approach to handling it. His comments also ignored the fact that 93 percent of Black Lives Matter protests were completely peaceful. I contrasted such practical policy decisions to “federal crimes encouraged by a US president who should know better.” And with that, the exchange ended.

I realize, of course, that this is just one such conversation among millions of exchanges among friends and relatives with contrasting views across the country. I did not completely disagree with all of his concerns, but I also was deeply puzzled as to how those of us worried about the future of democracy when it is under attack by followers of a demagogue like Trump can wrestle with jello or shadow-box with phantoms, given the vague and disingenuous statements with which we are confronted, including some of his.

In the meantime, speaking of stealing elections, we are watching some amazing voting rights shenanigans, to say nothing of phony “audits,” at the state level. What will we say when the second insurrection anniversary rolls around? Will anything have changed?

Partial Bibliography: Recent Books on President Donald Trump and/or the Insurrection

Johnston, David Cay. The Big Cheat: How Donald Trump Fleeced America and Enriched Himself and His Family. Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Karl, Jonathan. Betrayal. Dutton, 2021.

Leonnig, Carol, and Philip Rucker. A Very Stable Genius. Penguin Press, 2020.

Leonnig & Rucker. I Alone Can Fix It. Penguin Press, 2021.

Raskin, Jamie. Unthinkable: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy. Harper, 2022.

Schiff, Adam. Midnight in Washington: How We Almost Lost Our Democracy and Still Could. Random House, 2021.

Woodward, Bob, and Robert Costa. Peril. Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Woolf, Michael. Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House. Little Brown, 2018.

Jim Schwab

Fighting Lunacy with Lunacy

Thanks to the New York Times, I learned over the weekend that birds are not real. Oh, the information has been out there, and I don’t know how I missed it. Perhaps I am just not tuned into the metaverse, being over thirty[1] and all . . . . but I just did not catch on. Now I know. I understand.

You see, the birds have long since been replaced with drones that are surveilling our every movement. It is important that all right-thinking Americans be aware of their real purpose. Join the Birds Aren’t Real movement and find out. I personally intend to alter my disguise daily when I go outside so that the bird-drones can never identify me as the same person twice. Tweet the warning. Tweet it wide.

Okay. Let me keep this blog post shorter than my usual ruminations and just point you to the Times article by Taylor Lorenz that brings attention to what I think is one of the most effective satires on disinformation that I can recall in a long time. As the article reports, “Birds Aren’t Real” is the increasingly popular fabrication of Peter McIndoe, a college dropout who moved to Memphis, but grew up home-schooled in a conservative Christian family outside Cincinnati and later in Arkansas. It began as McIndoe’s spontaneous joke against pro-Trump counterprotesters at a women’s march in early 2017, after Trump had been inaugurated. It grew on social media to the point where 20 million people have viewed a TikTok video in which an actor portraying a CIA agent confesses to having worked on bird drone surveillance. “Birds Aren’t Real” paraphernalia, such as t-shirts, are available. Why do birds sit on power lines? That’s how the drones are recharged. The whole “conspiracy” has grown its own subculture, in which followers are in on the joke and those who take it seriously, well—they’re seen as

having bigger problems than just bird drones.

Some supporters apparently refer to their brand of conspiracy satire as “fighting lunacy with lunacy.” Yes, there is still a need for the House Select Committee to continue its investigation into the January 6 pro-Trump riot in the nation’s Capitol. Numerous people were killed and injured, and it is serious business. It is important for the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office to pursue the Trump Organization for tax fraud, for the New York Attorney General to continue her investigation, for charges of election tampering to be pursued against Trump in Georgia.

But we can also laugh because, if there is one thing the true believers in disinformation cannot abide, it is not being taken seriously. Trump himself, who suffered a secret humorectomy[2] by alien doctors at some unidentified point in his adolescence, especially cannot handle being an object of satire or ridicule. So, join the joke: Birds Aren’t Real. Your belly laugh at the absurdism involved will make your day and help keep you healthy.

And remember, if some bird poop lands on your head, save it for evidence. It’s all part of the plan to make you believe. Just make sure you can trust the people who do the lab test. 😊

Jim Schwab

[1] Unfortunately, I passed that age in 1980, before PCs and the Internet even existed on any large scale, but I’ve struggled to overcome this limitation. I live in fear of the solution revealed in the 1960s hippie movie, Wild in the Streets. I mean, since the 2016 election, you just never know what might become possible.

[2] This is the surgical removal of one’s sense of humor, including the ability to laugh at yourself. You won’t find the term in medical dictionaries because the coverup of such surgeries is all part of the conspiracy. If you must ask which conspiracy, you are clearly gullible and have bigger problems than the rest of us can solve. You may even have been an involuntary and unwitting victim of such surgery at a young age.

Private Costs of Disaster Prevention

The recent collapse of the Champlain Towers in Surfside, Florida, has cast a spotlight on numerous issues concerning building maintenance, private and public decision-making processes, potential (but highly uncertain) corrosive impacts of sea level rise, and even the continuing exposure of rescue workers to COVID-19, in addition to environmental and occupational hazards. That is all in addition to the governance questions surrounding condominium boards, given the news of past debates about deferred but expensive maintenance once consultants revealed structural deterioration in the 12-story complex.

I wish to be clear about my purpose in writing this post. As an urban planner and researcher, I have doggedly sought to focus on known facts and accurate assessments of hazardous situations of any type. Sometimes, the truth is clear enough. In others, it is wise to withhold judgment while raising questions that deserve thoughtful answers. In this instance, there are so many aspects to the story of the condo building collapse that caution is the appropriate approach because new facts seem to emerge daily. One question—why the North Tower did not collapse while the South Tower did—may compel further inquiry on the role of condo boards in driving decisions about investing in maintenance before catastrophe strikes, but further investigation may reveal many nuances to that story as well. Complete answers are not always simple or obvious.

I have no intention of rushing to judgment on the tragedy in Surfside. But I do wish to focus on one issue that I know is endemic to housing development on a nationwide basis: the roles and responsibilities of homeowners associations (HOA) for managing and maintaining property. Condo boards are one specific subset of HOAs, based on the nature of the buildings. But the issues are not limited to such buildings; they can easily affect the management of townhouse developments and gated subdivisions as well.

Five years ago, when the American Planning Association (APA) and the Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM) collaborated to produce a Planning Advisory Service Report, Subdivision Design and Flood Hazard Areas, we confronted one ticklish issue that concerned us greatly, albeit with regard to flood (and some other natural) hazards rather than structural integrity of tall buildings. The underlying issue, however, dealt with the capacity of privately governed homeowner associations to manage, finance, and maintain hazard mitigation infrastructure over time. Of course, one can easily broaden the definition of such infrastructure to include structural integrity repairs in a situation where buildings can potentially collapse, just as it might include the need to maintain the structural integrity of bridges to prevent such tragedies as the collapse of the I-35 bridge over the Mississippi River in the Twin Cities in 2007. There is considerable room for flexibility in defining the issue so long as the focus remains on public safety.

Our concern at the time was the potential for a financially challenged homeowners association or special district to fail to maintain critical infrastructure before a natural disaster leads to catastrophic failure, whether because of flood, landslide, earthquake, or wildfire, among other possibilities. Chad Berginnis, the executive director of ASFPM, alerted us to an article published by two lawyers involved in owner association litigation in California, Tyler Berding and Stephen Weil. They offered several examples of such situations including Bethel Island, which sits in the Sacramento Delta and includes about 2,500 residents whose homes are protected by more than 11 miles of levees that

circle the island, just 12 miles from the Greenville Fault. Throughout the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the potential cascading impact of an earthquake triggering massive flooding with failed levees is a nightmare of major proportions. However, residents had defeated a proposed parcel tax to finance improvements through the Bethel Island Municipal Improvement District (BIMID), leaving the district broke and laying off staff. Berding and Weill offered a series of suggestions for better planning and management of these situations.

Whether the case involves a special district like BIMID or special assessments imposed by an owner association board, the issue is the local or private responsibility for financing and maintaining the protective infrastructure to avert such tragedies. Disasters are almost never solely a function of natural forces affecting human communities. They are also a function of the location, condition, and resilience of those communities, and the greater the exposure, the greater is likely to be the long-term cost of restoring that resilience over time to prevent catastrophic loss. In many cases involving floods, landslides, or earthquakes, insurance may be unavailable or financially problematic. The ultimate result can be a bankrupt association and property owners who cannot recover their losses, let alone rebuild, yielding a combination not only of loss of life and property, but of financial calamity as well.

Pad-mounted Transformer in a floodplain not elevated. Photo by Chad Berginnis from PAS Report, used with his permission.

In the report, we sought in several ways to address the issues posed by these dilemmas. We noted, for instance, that as of 2016, the Community Associations Institute reported that 66.7 million people, about 20 percent of the U.S. population, lived in some 333,600 common-interest communities, 55 percent of which were homeowners associations, the rest either condominium or other community associations. One result is the transfer of responsibility for infrastructure within a subdivision from the municipality permitting it to the HOA itself. The long-term problem is that association leadership not only changes over time but often lacks expertise pertaining to the significant risks and responsibilities involved. We suggested that local planning and other agencies extend technical assistance to overcome this gap. This gap, however, remains a serious problem in many communities. When disaster strikes, the idea of having shifted responsibility will become transparently short-sighted because the city or county will be providing emergency response and assistance, just as is happening in Surfside. It is impossible to ignore a disaster.

We noted that many such associations assume responsibility for stormwater infrastructure, such as detention ponds, seawalls, and levees, or even private dams. If they fall into disrepair, the flooding consequences can be severe, so provisions for inspection and maintenance are critical. It is vital for such association boards to understand, for instance, that levees are never totally flood-proof and failure can have various causes. Privately built and owned levees exist across the nation, many in poor condition, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.

In short, these owner associations have assumed responsibility for some key areas of local flood risk management, including ponds, spillways, erosion and sediment control, flood control structural repairs, drainage improvements, managing vegetation that reduces flood risk, bridge maintenance, and open space management, among other possibilities. Given the potential financial and expertise limitations of these private associations, it may be incumbent upon local governments, in approving development, to assert some degree of control over the standards for approval, for which we offered several major recommendations for requirements related to maintenance costs and final plat approval.

There is, in the end, no perfect way to ensure adequate protection against disaster, but we were hoping to raise the level of concern and discussion, and attention to detail, in the relationships between local governments and owner associations as a way to avert tragedy and financial meltdown following disaster. It is not my intent here to explore the issue in depth but to introduce readers to the depth of the questions that these situations entail. Those wishing to learn more can follow the links to additional resources.

Jim Schwab

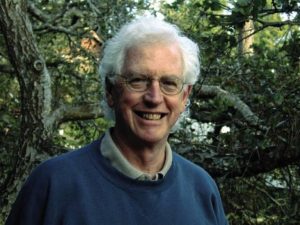

Softly Persuasive Planning Pioneer

I first met Ken Topping at the American Planning Association (APA) office in Chicago on a cold day in January 1994. Chicago was suffering one of its classic Arctic blasts at something like -20°F. Ken, a tall, very polite, and articulate gentleman, had his heavy winter coat for the ride back to O’Hare International Airport toward the end of the day. On January 17, just a day or so before he arrived in Chicago, the Northridge Earthquake struck Los Angeles, an area where he had worked for many years. Ken, who was already developing a significant history of advancing what was then the nascent role of urban planning in responding to disasters, became immediately involved. Exactly one year later, on January 17, 1995, the Great Hanshin earthquake leveled much of Kobe, a major city in Japan. With his extensive acquaintances there, Ken was again on the scene.

At the time, I gently needled him that trouble followed him wherever he traveled. But the reality was that Ken took the lead in planning solutions to some of the world’s most vexing environmental challenges: natural disasters. It took years for me to understand the degree to which that initial meeting with Ken changed my life and my perspectives on what I wanted to accomplish as a professional planner. Ken lured me into the world of disaster recovery and resilience planning in a way no one else did.

When we met, it was Bill Klein, then the research director at APA, who introduced us. Just a few months before, Bill, who had somehow negotiated a modest contract with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to produce a Planning Advisory Service (PAS) Report on planning for post-disaster recovery, offered me the opportunity to manage the project. This was not because I had any great expertise in the subject. It was because no one else at APA did, either, but I at least had a strong background in environmental planning, and disasters are, at least in part, an environmental problem. Actually, I learned, they are many problems rolled into one, and what I was about to undertake was a challenge well above any I had encountered before, even though I was already completing a book—my second—about environmental justice. But that left the question of why Ken Topping, with noteworthy contributions to the disaster field behind him, should be dealing with a greenhorn like me.

That’s not the way he saw it. Or ever saw it. If Bill had confidence in me, then for Ken it was a chance to mentor someone new to the field and help shape the project at its roots. Over the next few years, as the project grew and expanded from its original ambitions, Ken introduced me to numerous players in this then small arena of planning to reduce the impacts of natural hazards. I did not fully appreciate the significance of some of the people I met, a fact I still regret, but it was all such new territory that I did not always fully understand who was who.

Leaders of Tomorrow

My experience with Ken was far from unique. He mentored, nurtured, and influenced the professional development of people who became some of my best professional friends and colleagues in the growing subfield of hazards planning.

Ken and US-Japan team members meeting with community leaders of the Shin-Nagata North neighborhood that was heavily damaged in the 1995 Kobe earthquake. On the front row from left to right are: Robert Olshansky, Laurie Johnson, Kazuyoshi Ohnishi, and Ken Topping (U.S. team leader). Photo provided by Laurie Johnson.

Robert Olshansky, now professor emeritus at the University of Illinois and living in the Bay Area, met Topping and Laurie Johnson, then a young planner with a bachelor’s degree in geophysics, at a conference of the Central United States Earthquake Consortium in June 1994 in Louisville, Kentucky. The conference, which I also attended, drew mostly engineers, so these three planners “stayed up late in animated conversation,” Rob recalls. Frankly, I don’t remember much of what I did there, but I do recall meeting Laurie either there or a month later at the Natural Hazards Workshop in Boulder, Colorado. I was very much the newcomer to this business back then, in any case. But Rob, Laurie, and Ken engaged in a round of post-Northridge earthquake research meetings in California, which led to a proposal, led by Topping, to compare the Northridge and Kobe earthquake recovery experiences. Eventually funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), their work began in 1998, but the important facet was that it involved extensive international collaboration between this American trio and four Japanese researchers. It was Ken who introduced Rob and Laurie to Japanese planning. Rob confesses he had never been to Asia before the Kobe earthquake, but he and Laurie developed close connections in Japan who remain good friends 25 years later. Rob says it was Ken who insisted on the close collaboration with the Japanese and helped select the neighborhoods they chose for comparative study.

Ken with the US-Japan team conducting a long-term comparative study of rebuilding in Los Angeles and Kobe following the 1994 and 1995 earthquakes, respectively, during a team meeting in 2000 in Kobe. Left to right are: Robert Olshansky, Laurie Johnson, Ikuo Kobayashi, Hisako Koura, Yoshiteru Murosaki (Japan team leader), Kazuyoshi Ohnishi, and Ken Topping (U.S. team leader). Photo provided by Laurie Johnson.

The remarkable aspect of all this for Laurie Johnson, now a prominent hazard planning consultant based in San Rafael, California, was Ken’s acceptance and support though, she says, “I was barely in my 30s and had only a few years of relevant professional experience” when they first met. Their first contact, she says, came in 1990, when Ken spoke at the International Symposium on Rebuilding after Earthquakes, hosted at Stanford University by Spangle Associates, the firm for which she was then working. Spangle had produced a study that was among the first I studied in this emerging field, examining four case studies of post-disaster recovery. It profoundly influenced my view of what happens to communities in a disaster.

Ken, says Laurie, “wowed the group with his presentation on LA’s efforts to prepare a first-ever, pre-disaster recovery plan for the city before a major disaster like an earthquake struck.” Ken was then the planning director of Los Angeles. Fortunately, a draft of what became the Los Angeles Recovery and Reconstruction Plan had been completed when the Northridge earthquake occurred. The city formally adopted it a year later. Another NSF study led by Spangle Associates, in which Laurie was involved, found “that the plan was instrumental in contributing to the high level of staff performance” after the earthquake, helping most city departments to understand their responsibilities and prepare to perform them.

Innovations