The subtitle to this headline for many people might be: Who Cares? As a term of art, green infrastructure may be popular with landscape architects, civil engineers, and urban planners, among a few other allied professions, but it does not often mean much to the average person. Many people may struggle to define infrastructure even without the word green in front of it.

Infrastructure generally refers to those modern systems, such as roads, bridges, and utility grids that allow our cities and regions to function effectively. Recognizing that the value of infrastructure lies in the services it provides, green infrastructure has been distinguished from traditional gray infrastructure by focusing on the use of natural systems, such as wetlands and urban forests, to protect or enhance environmental quality by filtering air pollution, mitigating stormwater runoff, and reducing flooding. It stands to reason that such natural systems are most likely to provide such “ecosystem services” well when we respect and preserve their natural integrity. It also stands to reason that, to the degree that such systems face threats from urban sprawl and urbanization, their ability to perform those services for human populations is diminished. To say that development has often helped to kill the goose that laid the environmental golden egg is to state the obvious, no matter how many people want to avoid that truth. That does not mean that our cities cannot or should not grow and develop. It does mean that, using the best available natural science, we need to get much smarter about how it happens if we want to live in healthy communities.

I mention this because, as part of the American Planning Association staff pursuing such issues, I spent three days in Washington, D.C., last week at a symposium we hosted with U.S. Forest Service sponsorship on “Regional Green Infrastructure at the Landscape Scale.” We were joined by about two dozen seasoned experts not only from the Forest Service and APA, but from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, several national nonprofits, and others to sort through the issues impeding better planning for green infrastructure. We explored major hazard-related issues such as wildfires, flooding, and coastal storms and how green infrastructure can or should function in relation to them.

This matters because there are huge costs associated with the way we choose to develop. There can also be huge benefits. Whether the ultimate ledger in any particular region is positive or negative is largely dependent on the approach we choose, and that is heavily dependent on how broadly or narrowly we view our responsibilities. Historically, in America, we have been rather myopic about the damage we have done to our environment, but our perspective has become more comprehensive over time, starting with the conservation movement in the late 1800s. But today, as always, there are undercurrents of more myopic attitudes and impatience with the more deliberate and thoughtful calculations a more long-term view requires. There is also the simple fact that understanding issues like climate change requires some degree of scientific literacy, something that is missing too often even in some presidential candidates.

But it helps to drill down to specific situations to get a firm sense of consequences. For instance, the Forest Service budget is literally (and figuratively) being burned away by the steadily and rapidly increasing costs of fighting wildfires. That is in large part because the average annual number of acres burned has essentially tripled since 1990, from under 2 million then to about 6 million now. As recently as 1995, 16 percent of the agency’s budget went to suppressing wildfires. Every dollar spent on wildfires is a dollar removed from more long-term programs like conservation and forest management. By 2015, this figure has risen to 52 percent, and is projected to consume two-thirds of the agency’s budget by 2025. Clearly, something has to give in this situation, and in the present political situation, it is unlikely to be an expansion of the Forest Service budget. At some point, a reckoning with the causes of this problem will have to occur.

What are those causes? Quite simply, one is a huge expansion in the number of homes built in what is known as the wildland-urban interface (WUI), defined as those areas where development is either mixed into, interfaces with, or surrounds forest areas that are vulnerable to wildfire. The problem with this is that every new home in the WUI complicates the firefighters’ task, putting growing numbers of these brave professionals at risk. Every year, a number of them lose their lives trying to protect people and property. In an area without such development, wildfires can do what they have done for millennia prior to human settlement—burn themselves out. Instead, a century of aggressive fire suppression has allowed western forests, in particular, to become denser and thus prone to more intense fires than used to occur. The homes themselves actually represent far greater densities of combustible material than the forest itself; thus fires burning homes are exacerbated by increased fuel loads. In addition, prescribed fire, a technique used to reduce underbrush in order to reduce fire intensity, becomes more difficult in proximity to extensive residential development. A prescribed fire that spun out of control was the cause of the infamous Los Alamos, New Mexico, wildfire in 2000. The entire situation becomes highly problematic without strong political leadership toward solutions.

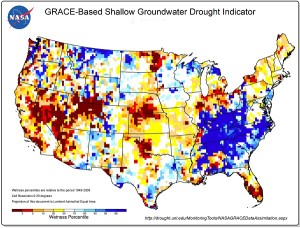

At the same time, denial of climate change or even reluctance to broach the subject does not help, either. It compounds the difficulty of conducting an informed dialogue at a time when increased heat and drought are likely to fuel even more wildfires of greater intensity. The recent major wildfire around Fort McMurray, Alberta, displacing thousands of people, may be a harbinger of things to come.

That is just one sample of the issues we need to confront through a larger lens on the value of large-scale green infrastructure and regional cooperation to achieve positive environmental results that also affect issues like water quality and downstream flooding. Because we could produce an entire book on this issue—and the suggestion has in fact been made that we do so—I will not even attempt here to lay out the entire thesis. Rather, it may be useful to point readers to some resources that I have found useful in recent weeks in the context of writing for another project on green infrastructure strategies. Most of these are relatively brief reports rather than full-length books, enough to give most readers access to the basics, as well as references to longer works for those so inclined.

On the subject of water and development in private forests, a Forests on the Edge report, Private Forests, Housing Growth, and Water Supply is a good starting point for discussion. Because planning to achieve effective conservation at a landscape scale requires collaboration among numerous partners, an older (2006) Forest Service report, Cooperating Across Boundaries: Partnerships to Conserve Open Space in Rural America, may also be useful. With regard to wildfires, a recent presentation at a White House event by Ray Rasker, executive director of Headwaters Economics, a firm that has specialized in this area, may also be useful for its laser focus on trends and solutions with regard to development in the wildland-urban interface and the need for effective, knowledgeable local planning in areas affected by the problem. But I would be remiss if I did not bring readers’ attention back to a 2005 APA product of which I was co-author with Stuart Meck: Planning for Wildfires. It could probably use some updating by now, but every one of our central points, I believe, remains valid.

Happy reading to all!

Jim Schwab